eBook - ePub

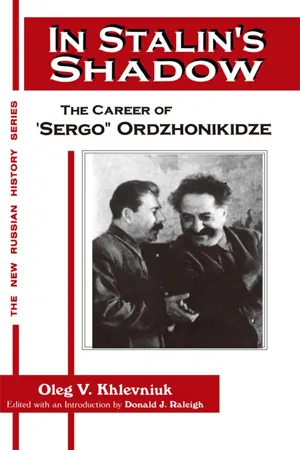

In Stalin's Shadow

Career of Sergo Ordzhonikidze

- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

In Stalin's Shadow

Career of Sergo Ordzhonikidze

About this book

In the voluminous secret history of the 1930s, one episode that still puzzles researchers is the death in 1937 of one of Stalin's key allies - his fellow Georgian, G.K. Ordzhonikidze. Whether he took his own life or, like Kirov, was murdered, the case of Ordzhonikidze intersects several long-debated problems in Soviet political history. What role did Politburo members play in decision making during the Stalin era? What formed the basis of Stalin's alliances? Were there conflicts between Stalin and his comrades and, if so, how far did they go? Was there in fact opposition to Stalin? These and other questions are addressed by one of Russia's best young historians whose pioneering work in previously closed party and government archives is refining our understanding of the political history of the Stalin era.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access In Stalin's Shadow by Oleg V. Khlevniuk,David J. Nordlander,Donald J. Raleigh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Making of a “Party Professional”

“Before 1905 I was a student, and then served for several months as a medical assistant. In the remaining years before the Revolution of 1917, I was a party professional,” wrote Ordzhonikidze on a party questionnaire in 1931.1 Party professionals, dedicating their lives to the struggle with the tsarist regime and subjugating their personal interests to those of the party, constituted the majority of those who came to power in Russia in October 1917.

Despite the fact that the fate of each of these people took shape differently, there evidendy existed common life experiences and circumstances that helped form the revolutionary type. As a rule, revolutionaries were forced to grow up early or had to deal with adult crises as children: they were subjected to humiliation and national oppression, and acutely felt their positions as social outcasts. The tsarist regime, whose cruelty engendered great bitterness, successfully increased the ranks of its opponents. Revolutionaries often were motivated by hatred for an all-encompassing injustice and oppression rather than by some doctrine. Often, their character and upbringing prevented them from leading quiet or normal lives. They preferred a dangerous struggle with the government to a steady rise up the career ladder. Prison, exile, flight, and emigration—these were the experiences that formed and defined their vision of the world and its specific characteristics.

The war, unleashed by the European governments in 1914, strengthened the resolve of those revolutionaries who believed that capitalism was in decline. It was a shock for a whole generation that magnified hatred and reduced the price of human life to a minimum. War brought about the revolution—the stellar hour of the revolutionaries.

Ordzhonikidze was one of those whose background and character led directly to revolution. He was born in October 1886 to an impoverished noble family in the Georgian village of Goresha. His mother died while he was still an infant, and his father when Ordzhonikidze was ten. Thanks to relatives, he finished a two-year secondary school and a doctor’s assistant program. At seventeen, he joined the Russian Social Democratic Workers’ Party (RSDRP), worked at an underground printshop, and distributed leaflets. It was at this point that he befriended the desperate Kamo,* apparently seeing in him a “kindred spirit.” In 1905, he threw himself into the revolutionary cause by taking the most dangerous assignments. He was arrested while transporting arms that December. He spent several months in jail, where he participated in the growing hunger strike movements. His comrades still at large helped him get released on bail before he went to trial. When the threat of arrest loomed again, he fled to Germany. Soon he returned to Baku, and in 1907 was arrested once more. After a short twenty-six-day prison term, he continued to carry out party work under an alias in Azerbaidzhan, where Stalin was also serving.

In November 1907, he was arrested for the fourth time, imprisoned in a fortress, and then exiled indefinitely to Siberia. Ordzhonikidze fled after several months of exile, returned to Baku, and after a while crossed over into Persia. When revolution broke out there, the Bolsheviks in the Caucasus sent Ordzhonikidze to help Iranian insurgents direct an armed guard.

Ordzhonikidze traveled to Paris in the spring of 1911, where he met Vladimir Ilich Lenin (1870–1924) for the first time. While there, he became a student at the party school at Longjumeau, organized to prepare Bolsheviks for revolutionary work in Russia. He did not stay in school long, due to a bitter struggle in the party. Consequently, Lenin sent Ordzhonikidze to Russia to help convene the Sixth Conference of the RSDRP. Ordzhonikidze successfully completed this assignment and was elected to the Central Committee at the Prague Conference in January 1912. He returned to Russia following the conference, and worked spreading information to members of various organizations who had been co-opted into the Bolshevik Party Central Committee at the Prague Conference. During this time he visited Vologda, where Stalin was living in exile. Together, Stalin and Ordzhonikidze left for the Caucasus. After some time they returned to St. Petersburg, where Ordzhonikidze was again arrested in April 1912.

This arrest proved to be a serious matter. The police established Ordzhonikidze’s true identity, and recounted all his previous transgressions, including the transport of arms in 1905. Ordzhonikidze spent three years in Schlüsselburg prison, and in the fall of 1915 was sent to Siberia into permanent exile. It was outside Yakutsk that he learned of the February Revolution. At the end of May 1917, Ordzhonikidze returned to Petrograd with his Bolshevik comrades.

For the month that he remained in the capital, Ordzhonikidze was fully engaged in the political struggle: he joined the Petrograd Bolshevik Committee, often addressed rallies, and carried out party work at the city’s largest factories. He once again worked closely with Stalin in Petrograd. At the same time, relations between Ordzhonikidze and Lenin strengthened. He accompanied Lenin to Razliv on an assignment from the Central Committee, and at the Sixth Congress he reported on Lenin’s decision not to appear in court.*

In the fall, Ordzhonikidze traveled to Transcaucasia for a short visit, returning to Petrograd before the Revolution on October 24. He was sent to Pulkovo to fight against units loyal to (the leader of the Provisional Government) Aleksandr F. Kerensky (1881–1970).

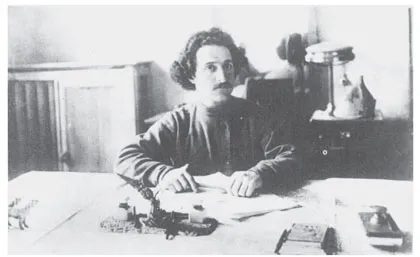

Sergo Ordzhonikidze during the Russian Civil War.

During the Civil War, Ordzhonikidze spent more than three years on various fronts. He was a special Bolshevik Commissar of the Ukraine, South Russia, and the North Caucasus, and fought in the battle for Tsaritsyn. He found himself on the western front in 1919, where Stalin was a member of the Revolutionary Council. In 1920, Ordzhonikidze was a member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Caucasian Front and a chairman of the North Caucasus Revolutionary Committee. He entered Baku victoriously at dawn on May 1, 1920. Afterward, he became embroiled in the desperate struggle for the consolidation of Soviet power in Azerbaidzhan and the North Caucasus. When an uprising broke out in Dagestan and the Terek Oblast in October 1920, Stalin, who had arrived from Moscow, praised Ordzhonikidze’s work highly in reports to Lenin and the Central Committee:

The mountaineers have shown their best side, and in the majority of cases fought with weapons in hand alongside our partisans against the bandits; undoubtedly, Ordzhonikidze and the Caucasus Bureau have followed our policy accordingly, uniting the mountaineers with Soviet power. … A thousand volunteers (from Dagestan) fought alongside us and together with our partisans drove out the counterrevolutionary insurgents—this fact is characteristic, once again, of the correct policy of Ordzhonikidze and the Caucasus Bureau.2

Sergei M. Kirov (left) and Ordzhonikidze in Baku in 1920.

After securing Azerbaidzhan, Ordzhonikidze and his assistants hurried to establish Soviet power throughout Transcaucasia. Armenia was annexed in December 1920. Ordzhonikidze then rushed to Georgia, and urged Moscow to intervene with the Red Army there. Moscow held back, restrained Ordzhonikidze, and demanded that he be careful. But not for long. In February 1921, the Eleventh Army entered Tiflis. For Ordzhonikidze and other Georgian Communists, this event undoubtedly had special significance.

Because of the war in Transcaucasia, Sergo Ordzhonikidze was not able to attend the Tenth Party Congress, which opened in Moscow at the beginning of 1921. Several delegates to the congress opposed Ordzhonikidze’s reelection to the Central Committee. Only Stalin’s, and most importandy, Lenin’s intercession preserved Ordzhonikidze’s place in the leading party organ. While the stenograms of this session of the congress are not available, the memoirs of Anastas I. Mikoyan (1895–1978)* provide adequate detail concerning the arguments surrounding Ordzhonikidze’s candidacy:

Several military delegates from the North Caucasus unexpectedly shouted their objections to Ordzhonikidze’s candidacy from their seats. These delegates sat in the last row and made noise heard throughout the hall. One of them rose to the podium and began to say that Orzhonikidze yells at everyone, orders everyone around him, ignores the opinions of local party members, and therefore should not be in the Central Committee. This demagogic outburst influenced the mood of the delegates, many of whom did not even know Ordzhonikidze.

Speaking in a soft, quiet voice, Stalin rose in defense of Ordzhonikidze. He provided biographical details, recounting Sergo’s work in the underground and on the fronts of the Civil War. Further, he recommended Ordzhonikidze’s selection to the Central Committee. It was clear, however, that he could not convince the delegates, who continued to stir up a row.

Then Lenin spoke in defense of Sergo’s candidacy, offering the following summation: I have known Comrade Sergo for a long time, from the underground days, as a dedicated, energetic, fearless revolutionary. He showed his true colors in emigration, played an outstanding role in preparing for the Prague Conference in 1912, and was elected to the Central Committee. He carried out active work in Petrograd preparing for and conducting the October Revolution. He proved himself to be a brave and capable organizer in the Civil War. But the comrades who criticized Sergo correcdy noted one thing; that is, he yells at everybody. This is true. He speaks loudly, but you don’t know why. When he speaks with me, he also shouts. This is because he is deaf in the left ear, Lenin noted with affection. Therefore, he shouts—he thinks that nobody hears him. But one should not pay any attention to this shortcoming….

This brought smiles and even good-natured laughs from the delegates. It became clear that Lenin, in supporting Sergo’s candidacy, defeated all opposition … [and this was important] for there had been serious apprehension that many votes would be cast against him. In a secret ballot following Lenin’s speech, Ordzhonikidze received an overwhelming majority of votes. Like Dzerzhinskii, he received 438 votes out of 479….3

Ordzhonikidze undoubtedly knew what happened at the congress and was grateful to Lenin and Stalin. At the time, he belonged to a group of party leaders who unquestioningly supported Lenin in his rivalry with Lev Davidovich Trotsky (1879–1940). However, at the end of 1922 a power shuffle occurred at the highest echelons that directly affected Ordzhonikidze.

Beginning in 1921, Lenin was often ill. In his absence, a “troika” led the party and government: Lev B. Kamenev (1883–1936), Lenin’s deputy in Sovnarkom and the Council of Labor and Defense (STO), presided over Politburo meetings; Stalin headed the Central Committee’s apparatus; and Grigorii E. Zinoviev (1883–1936)led the Executive Committee of the Communist International (Comintern). At first, the “troika” trod cautiously and in accord with Lenin’s wishes. As the party leader’s health deteriorated, however, his associates began to prepare seriously for the transfer of power. Returning to work for a short time in 1922, Lenin objected to the concentration of “unlimited powers” in Stalin’s hands and certain attitudes of the “troika” on many questions. Lenin decided to demote his comrades-in-arms.

He chose disagreements on the nationality question as one of the grounds for attack. Their essence is well known: Stalin suggested that the republics be made autonomous, while Lenin backed an all-union government. A major feature of this conflict was the so-called Georgian Affair, which received wide publicity and took on great significance.

The conflict lay in the sharp opposition existing between the Central Committee of the Georgian Communist Party and the Transcaucasian Regional Party Committee (kraikom), between the group of Budu Mdivani (1877–1937) and Ordzhonikidze. Personal rivalry and ambition collided in the arguments concerning the creation of a Transcaucasian federation. Ordzhonikidze, promoting Moscow’s policy and receiving the continual support of Stalin, spoke on behalf of a federation of the three Transcaucasian republics, while Mdivani’s group insisted on Georgia’s independent entrance into the USSR without a Transcaucasian federation. Passions became white hot. Ordzhonikidze, incited by Stalin, acted aggressively and in a fit of anger struck one of the Georgian leaders, who called him “Stalin’s asss.”4

At the end of November 1922, the Politburo sent a special commission to Georgia under the leadership of Feliks E. Dzerzhinskii (1887–1926). Lenin closely followed this affair and the work of the commission, which accepted Ordzhonikidze’s version to Lenin’s dissatisfaction. “For all the citizens of the Caucasus Ordzhonikidze was the authority. Ordzhonikidze had no right to display that irritability to which he and Dzerzhinskii referred,” wrote Lenin.5 He decided to make this question a matter of principle—“to make an example out of Ordzhonikidze by punishing him,” and to battle Dzerzhinskii and Stalin for supreme power. Lenin planned to do this at the imminent plenum of the Central Committee. However, feeling that his illness would not permit his participation, Lenin sought Trotsky’s help: “It’s my urgent request that you should undertake the defense of the Georgian case in the party Central Committee. This case is now under ‘prosecution’ by Stalin and Dzerzhinskii, and I cannot rely on their impartiality. Quite to the contrary.”6 The next day, March 6, Lenin sent a letter to the leaders of the Georgian Communists, Mdivani and Filip Makharadze (1868–1941): “Dear comrades! I’m following your case with all my attention. I’m indignant over Ordzhonikidze’s rudeness and the connivance of Stalin and Dzerzhinskii. I’...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Editor's Introduction

- Russian Terms and Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. The Making of a "Party Professional"

- 2. At the Head of the Central Control Commission

- 3. The Lominadze Affair

- 4. The Head Manager

- 5. Ordzhonikidze and Kirov

- 6. Lominadze's Suicide

- 7. Stakhanovites and "Saboteurs"

- 8. Piatakov's Arrest

- 9. An Unhappy Birthday (Ordzhonikidze and Beria)

- 10. Rout of the Economic Cadres

- 11. Preparing for the Plenum

- 12. The Last Days

- 13. Murder or Suicide?

- 14. After the Funeral (Ordzhonikidze and Molotov)

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author