![]()

Part I

Overview of Art Therapy Research

![]()

Art Therapy Research Ideas, Tools, and Steps in the Process | 1 |

… the top of the mountain, the honorable kill the hunter makes, or a philosophical problem, or the quest for peace. One must enter absolutely into the process to be capable of enduring it to the end. To engage in the presence of the earth, of nature; to seek what is never easy; to fail as well as to succeed; to grow weary and ragged in the search and yet to persevere because the mountain does, indeed, have a summit, the war an end; to enter a depth and a distance that go so far beyond the ordinary routines of a day, or a life, that they bring you to the beginning, is to hunt.

—R. Rudner (1991, p. 75)

Research means to seek out, to search again; by our very natures we are seekers and searchers. When the researcher feels alive in pursuit of the desired discovery of something, the work becomes indistinguishable from the creative process art therapists know so well (Kapitan, 1998). Research yields knowledge that nourishes a profession, influences its future, opens closed minds, and brings forth new understandings not previously contemplated. Most important, research drives an exchange of critical conversations that shape understanding and practice, and help advance the collective knowledge of the field.

Despite the tremendous creativity that art therapists employ in their artistic or clinical work, and ever-growing evidence of sound research in the field, the very idea of research has been intimidating to many. Research can be hard to understand and involves acquiring a new vocabulary. It may feel irrelevant compared to what is expected day-to-day on the job. Some art therapists believe they have to fit their ideas into a rigid model of scientific research, which echoes their experience of trying to fit into the traditional clinical world and underscores a sense of powerlessness (Kapitan, 1998). They argue that research objectifies clients whose art therapy experience cannot be located in statistics or be available for measurement, prediction, and replication. Others reason that if we want to make claims about art therapy, we should base them on evidence, not personal belief. To do anything less is unhelpful to art therapy clients.

As Deaver (2002) asserted, when we think about clients and reason out how to work with them most effectively, we are already engaged in a form of research. We witness how art can be a catalyst for positive growth and change, or for reframing and disrupting self-defeating behaviors. We skillfully apply our knowledge and see with our own eyes how effective art therapy is for a diversity of human concerns. “Sometimes we are amazed by what happens in sessions, even in awe of the power of art therapy to bring forth the changes we observe,” Deaver wrote, but when questioned, “we can rarely explain with any precision or confidence” how we understand the work produced (p. 23). How do we know what is actually occurring during art therapy or what it is that contributes to a successful outcome? Research helps us locate these answers.

How is Art Therapy Knowledge Constructed?

What do you believe art therapists should know? Is your answer grounded in what you or the art therapy profession values? Now think about all you need to know when you are in a situation that demands the fullness of your professional skills, such as an encounter with a vulnerable client in a crisis. So many things are unknowable until you are in that specific moment with that specific client. Your insights and understanding are influenced by your view of reality and expressed through actions, ideas, and imagery in fluid practice. This “whole of knowing” can never be portrayed in theories and textbooks but instead rests on a particular and unique awareness that is grounded in the being and doing of a person.

Art therapy is not only a way of knowing but also a body of knowledge shared by art therapists and taken to be valid. Epistemology refers to the ways in which this knowledge is developed—that is, what should count as knowledge, what should be rejected, and what methods are appropriate for gaining the type of knowledge that is desirable. Research is organized around certain epistemological beliefs and worldviews that guide the choice of methods, approaches, and questions. Each paradigm has its own ways of realizing its aims. It is therefore essential for researchers to understand who they are and what they hold true. Before embarking on a research study, take some time to reflect on your beliefs about the situation you would like to tackle with research. Consider the different forms of knowledge about that reality and how you might approach that knowing.

What we accept as knowledge is not because it is “true,” but because it rests on evidence that is persuasive. As you will discover, research knowledge comes in different forms that co-exist yet vary in their explanatory, predictive, and interpretive power. Knowledge also varies in certainty; reflection on the constructive nature of research is a persistent, thoughtful activity that is renewed with each step of the research design.

Designing a Research Study

Research planning is a dynamic, creative process—akin to architecture and other fields of design. Whether planning a building or creating a website, designers must commit to the overall purposes of the project and follow inherent logical principles, such as the laws of physics in the case of a building or, in the case of a website, what is known about the people who will be using it. Research studies that are aimed at explanation and prediction require a structured design to allow data to be tested and logically linked to the variables being examined. Research that is oriented toward discovery is designed to maximize a researcher’s interactions with the data; the design may change as previously unknown variables or information emerge.

A research design is like a blueprint that, accordingly, must be worked out before conducting the study. The design process is dynamic, not static, and will vary for every individual art therapist. You might start with a clinical problem in the workplace that needs a solution or sparks an interest in studying it more intentionally. Or you may have a creative problem that can only be worked out in the studio. Some art therapists start at the beginning by identifying a question, while others discover an existing study that they would like to refute or extend with their own knowledge and interest. Keep in mind that the process of research design is not as neat or linear as any textbook discussion implies. But there are basic steps involved, regardless of the point of entry. These are:

- identifying the research question;

- creating a concept map;

- developing the problem statement;

- searching for and reviewing the literature;

- determining methodology;

- locating tools and resources for conducting the study;

- implementing the study within ethical boundaries;

- reporting and disseminating the results.

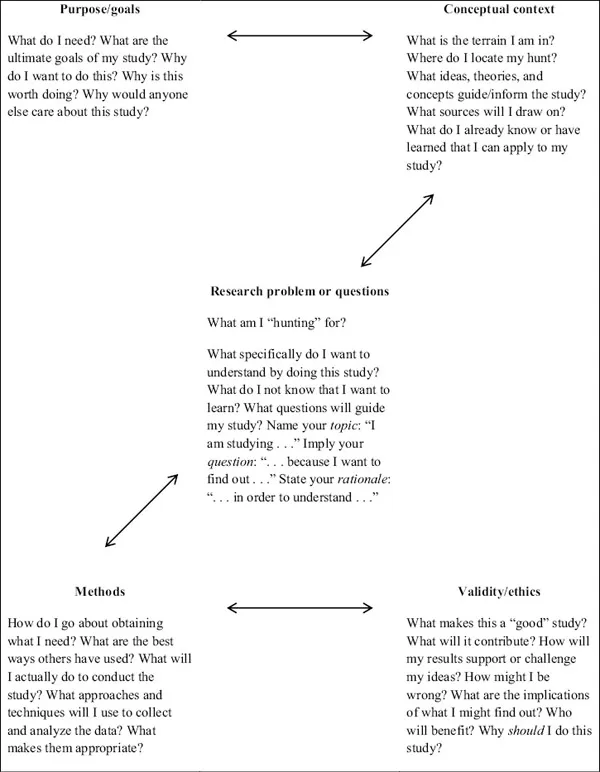

Especially for art therapists who are non-linear problem solvers, I recommend an interactive design model (Figure 1.1) adapted from Maxwell (2013). This schema guides research planning by tacking back and forth among five interacting, non-hierarchical components, with your question located in the heart or center of the process. Connected to the question are the purposes and conceptual aspects of the design, as well as operational aspects of proposed methods and related validity issues. Maxwell (2013) evoked the image of a rubber band to emphasize that these interacting elements are not rigid; however, they do exert certain constraints beyond which the design cannot stretch if it is to be effective.

Figure 1.1Interactive model for designing the study

Researchers may enter at any of the five points and move in either direction to flesh out the relationship among the study’s purpose, context, questions, methods, and validity. For example, you may have a good question and can think of methods to address it, but haven’t figured out why it is worth the time and energy. Paying closer attention to the context surrounding the question—by reading or reflecting on source knowledge that inspires it—will help uncover your motivations and purpose. Once clear about the purposes and context, it is easier to refine the problem more precisely and, in turn, be led to methods that will precisely gather what you need. As another example, a researcher starting at the validity point may have access to an important art therapy population but wonders about the risks involved for the participants. Clarifying these concerns will suggest appropriate methods for the site and, in turn, will point to a more precise research question. As you think through each step in this chapter, from research planning to carrying out the study and reporting results, you may want to return to this interactive map periodically and use it to refine your study’s design.

Step One: Identifying the Research Question

Research questions come from the clinic, studio, or other environments, usually in the form of a curiosity, concern, or problem. Because creative problem solving is basic to an art therapist’s daily work, potential research questions are always within reach. You may wonder why a client is behaving differently before or after a certain art therapy session. Perhaps you have discussed a particularly daunting clinical problem with your colleagues and would like to test out a different approach. Sometimes research questions appear while reading a study that gets you thinking about how the same situation might apply to your own practice—or might not apply because of a dynamic you’ve observed that the study did not take into account. You may want to replicate the study to test your observation or to modify the study in a way that captures your own interest. In your studio your artistic discoveries may have led to insights that you think others might want to try in their own work. Table 1.1 highlights the many sources art therapists use for their research questions.

Art therapists engage their creative interests in a breadth of topic areas, but not all questions are “researchable,” meaning that your questions should address a real need or problem that is significant to the field. As a springboard for generating research ideas, Deaver (2002) organized four broad areas in art therapy that uniquely lend themselves to research: (a) the therapeutic relationship, (b) art as assessment or a measure of treatment outcome, (c) art as a process or intervention, and (d) art therapy as a profession. Interesting, useful ideas that eventually produce researchable questions often begin with “What happens when …?” “What’s going on here?” “Why is art therapy done this way?” “I wonder what would happen if …?” and “How am I or my clients affected by …?” To be effective, a good research question has the following attributes (Bailey, 1991):

Table 1.1 Sources for research problems SOURCE | INFLUENCE ON RESEARCH PROBLEM |

Practical experience | An art therapist might observe a pattern or shift in client behavior or artwork and wonder about its relation to other elements in the therapeutic environment or relationship. Published example: Lee (2013) observed that immigrant children with behavioral difficulties in school displayed markedly different behaviors in art therapy. She documented evidence from video-stimulated interviews, discussions with teachers and parents, artwork, and case notes. |

Critique of art therapy literature | Art therapy literature might suggest a practice problem or provide a basis for replicating a study, applying it to a different context, or developing a pilot study to test it out. Published example: Graves, Jones, and Kaplan (2013) tested a variable in a published assessment by comparing drawings from different regions to determine whether environmental differences influence the drawing task. |

Gaps in theory and practice | An art therapist might compare what is known and unknown about a topic to locate missing information that would benefit the field. Or compare current practices with potentially better practices, or follow up on calls for research. Published example: Potash and Ho (2011) noted that art therapists focus more on the value of art making experience than the benefits of viewing art. Their study investigated “How does viewing and participating in an art therapy exhibit facilitate empathy for the artist and enhance the viewer’s understanding of mental illness?” |

Interest in untested theory | Investigating a claim in the literature provides uncharted territory for new research. Or an art therapist might apply a theory from a related field to art therapy. Published example: Having read that art therapists may resist using technology (Asawa, 2009), Peterson (2010) applied a model from a related field to discover how art therapists select, e... |