![]()

1.1What is mathematical cognition?

Mathematical cognition is a relatively new field of research that seeks to understand the processes by which individuals come to understand mathematical ideas. Mathematical cognition researchers are interested in how mathematical understanding and performance develops from infancy to adulthood, the factors that explain individual differences in mathematical performance and why some individuals find mathematics so difficult. It is an interdisciplinary field, drawing on psychology, education, and neuroscience, and cannot be reduced simply to one of these disciplines. To fully answer questions about mathematical understanding and processes involves an awareness of underlying brain processes, cognitive systems and their development, and the formal and informal activities that individuals engage in when learning mathematics. As would be expected for an interdisciplinary field, research in mathematical cognition employs a diverse range of methodologies including (but not limited to) experimental cognitive, neuroimaging, intervention and individual differences research.

Part of the motivation for this area of research comes from an increasing awareness that many individuals struggle with mathematics. In the UK, for example, it is estimated that 24% of adults have numeracy levels below that needed to function in everyday life, for example, to understand food pricing or pay household bills (Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, 2011). This pattern is replicated across many countries; the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) survey of 24 countries found that overall almost 20% of adults have low levels of numeracy and are unable to accurately deal with two-step calculations, or understand common decimals, percentages and fractions (OECD, 2013). These difficulties begin to arise early in schooling, for example the US National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in 2015 found that only 33% of 10-year-olds had reached the expected level of proficiency in mathematics (Kena et al., 2016). This is important because research has shown that poor mathematics skills in childhood have a negative impact on later health, wealth and quality of life (Hudson, Price, & Gross, 2009; OECD, 2013; Parsons & Bynner, 2005; Reyna, Nelson, Han, & Dieckmann, 2009). Mathematical cognition researchers believe that a better understanding of underlying mathematical processes can help us to identify why so many individuals struggle with mathematics, and consequently how to improve mathematical performance.

Having a positive impact on mathematics education and performance is one important motivation for studying mathematical cognition, but not the only one. Understanding the processes of mathematical performance is an ideal test case to explore deeper psychological questions. As we will show throughout this book, mathematical performance involves integrating formal, uniquely human, systems of symbolic representation with more basic, intuitive (and some suggest innate) systems for representing mathematical ideas. This pattern is repeated across many years of mathematics education during which students must integrate formal rep-resentations of mathematical concepts with pre-existing informal ideas developed from everyday life. The study of mathematical cognition therefore provides a window into deeper questions of how our cognitive systems draw on and are influenced by multiple sources of information. These questions go beyond the domain of mathematics and help us to understand the nature of our cognitive systems themselves.

Finally, the study of mathematical cognition also raises philosophical questions about the nature of mathematics itself. For instance, what actually is a number? Do numbers exist as abstract objects independently of humans (as so-called platonists would argue)? Or are they logical objects constructed within a given axiomatic system (as formalists would suggest)? Recent work on mathematical cognition opens up other possibilities that have not yet fully been considered by philosophers. For instance, perhaps numbers are simply tags for Approximate Number System representations (see Chapter 2). Considerations such as these have led some philosophers of mathematics to pay a great deal of attention to the mathematical cognition literature (De Cruz, 2016; Gaber & Schlimm, 2015; Giaquinto, 2007).

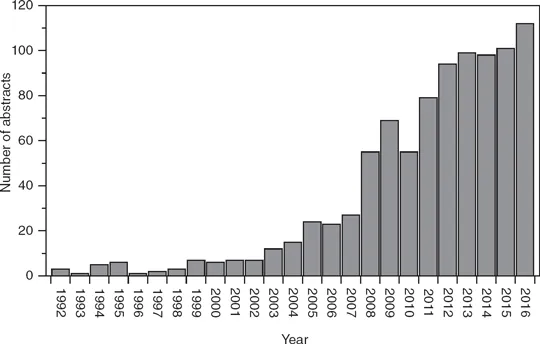

The field of mathematical cognition has grown rapidly over the past decade. For example, a citation search for the terms ‘mathematical cognition’ or ‘numerical cognition’ in Web of Science identified a marked increase in the number of items published since 2007 (see Figure 1.1). Developments such as a new journal, Journal of Numerical Cognition, launched in 2015 and a new society, The Mathematical Cognition and Learning Society, founded in 2016, demonstrate that the field has become established and is set to grow further. As the number of academics working in the field of mathematical cognition grows, it is likely that this is a topic that will increasingly appear in undergraduate and postgraduate psychology, neuroscience and education courses and therefore introduce a new generation of researchers to the field. We hope that this book will help in this endeavour by providing an accessible introduction to key theories, notable findings and ongoing debates in the field.

1.2The development of mathematical skills

As we describe in the following chapters, mathematical cognition research has made substantial advances in uncovering the processes involved in understanding mathematical ideas. To a large extent this work has focused on numeracy and arithmetic, rather than mathematical topics more broadly, and some major theories have been proposed about the nature of basic numerical representations. Less work has focused on higher levels of mathematics, although this is beginning to change.

Research with infants has explored the nature of numerical representations and questioned whether infants and young children are capable of processing numerical information before they have learnt symbolic representations (i.e. ‘three’ or ‘3’). Prominent theories have been proposed to suggest that, even without these symbolic representations, humans (and other animals) are able to represent approximate nonsymbolic quantity information. Studies have explored whether this ability is present from birth, whether it involves truly numerical processing, and if it is related to later, formal, mathematical skills.

The first recognisably mathematical activity that young children engage in is to learn the count list and understand what these numbers mean. Research has shown that this seemingly simple activity is in fact very complex and involves a protracted period of development before number words and symbols become grounded in meaning. The question of what gives symbols their meaning is yet to be fully established by researchers, although this is a topic of much current interest. Once children have learnt these number symbols they begin to use them in arithmetic operations. Research has shown that children draw on informal or intuitive understanding of arithmetic and attempt to integrate this with formal instruction and symbolic representations. True competency with arithmetic does not only involve the ability to carry out arithmetic operations, it requires knowledge of basic number facts, conceptual understanding of the operations and how they are related and the skill to choose appropriate strategies. Studies have shown that each of these aspects of arithmetic are important for overall performance, and that they all draw on basic symbolic number skills, as well as domain-general cognitive skills such as working memory and attention.

As children progress through school they are introduced to new and increasingly complex mathematical ideas and processes. Rational numbers require children to move beyond the count list as a basis for number representation and prove challenging for many. Algebra also serves as a particular stumbling block for many children. These new topics require children to become familiar with new forms of symbolic representation as well as important conceptual advances. Research has begun to identify several ways in which these new topics are difficult for children, for example where new topics directly challenge previously acquired meanings and intuitions, as well as proposing mechanisms to help improve children’s understanding. Finally, some individuals go on to study mathematics at higher levels, where again new systems of representations, ways of processing and conceptual ideas must be understood.

The following chapters of this book cover these areas in roughly developmental order. Individual chapters can be read alone to focus on specific topics, however, reading the chapters in order of development reveals key themes that cut across these individual topics. The challenge of acquiring new symbolic representations and grasping the meaning they encapsulate is a recurrent theme, which is as relevant for young children learning to count as it is for advanced students studying proof. The interplay between procedural skill (‘knowing how-to’) and conceptual understanding (‘knowing why’) can be seen at all levels of mathematical performance. The nature of expertise, i.e. the behaviours or skills that differentiate those who are proficient from those who struggle, is a relevant issue for expert mathematicians as well as children learning arithmetic. Finally, across many topics we see that earlier understanding can interfere with the later acquisition of ideas. As well as focusing on the patterns of performance and development of skills that are common to most learners, the following chapters also consider atypical development, and the reasons why a small proportion of individuals have particular difficulty with mathematical ideas and performance.

Throughout the book we have aimed to highlight key findings and theories within each topic and give a flavour of the methods and approaches used to investigate these. We also highlight some of the key unanswered questions within each topic that require the attention of researchers in this rapidly growing field.

![]()

2.1Introduction

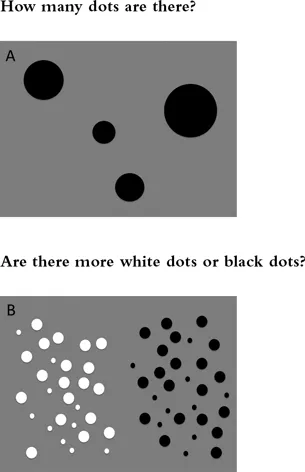

What do we mean by nonsymbolic numbers? We are surrounded by numerosity all day, every day, and we perceive nonsymbolic numerosity, i.e. the quantity of objects, typically in one of two ways. For small numbers of objects or tones, for example, we just seem ‘to know’ the exact number without having to count. People often say ‘the number just popped out to me’, ‘I just knew that there are three people’. In task A above, for example, we just see that there are four dots, whereas for larger numbers of objects we either need to count or to estimate their numerosity. We are also able to compare two sets of larger quantities accurately without counting, as long as the difference in numerosity between the two sets is large enough (for example, task B above). Counting depends on language abilities and will be discussed in Chapter 3. In this chapter we will focus on types of enumeration of objects that are language-independent.

Researchers have proposed two systems for language-independent numerosity processing: a system involved in small exact numerosity perception and a system for large approximate numerosity perception (often called the Approximate Number System [ANS]). We will review the evidence for those two systems in turn.

2.2Small exact system

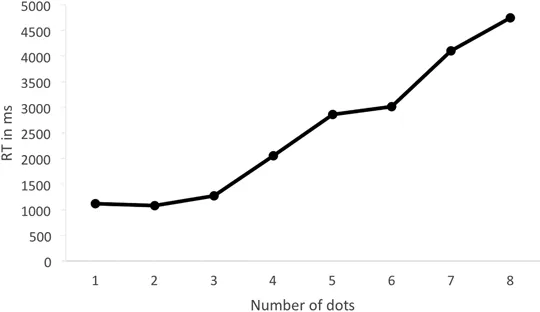

When participants are asked about the numerosity of briefly presented arrays of items, participants are fast, accurate and confident for small numbers of items (typically 1–4), but take longer, make more errors and are less confident the larger the numerosity. Figure 2.1 shows a typical performance pattern characterised by a discontinuity in the response time function around 3 or 4 objects. There is a small or no increase in reaction time (RT) for each additional item in the so-called subitizing range (1–3) and a larger increase per item outside the subitizing range (larger than 4).

This performance pattern was first formally described by Stanley Jevons in 1871 and has been replicated numerous times since (Klahr & Wallace, 1973; Logan & Zbrodoff, 2003; Mandler & Shebo, 1982). The term subitizing was coined decades later by Kaufman, Lord, Reese, and Volkmann (1949). To ‘subitize’ stems from ‘the classical Latin adjective subitus, meaning sudden, and the Latin verb subitare, meaning to arrive suddenly’ (Kaufman et al., 1949, p. 520). Subitizing was first described in the visual domain and much of the research has focused on enumeration of visually presented objects. Interestingly, subitizing has also been reported for auditory (ten Hoopen & Vos, 1979) and tactile (Plaisier, Tiest, & Kappers, 2009, 2010; Riggs et al., 2006) perception.

2.2.1The development of subitizing

Subitizing seems to develop before verbal counting (P. Starkey & Cooper, 1995) and subitizing-like performance patterns have been reported in infancy (Feigenson & Carey, 2005). Ten- and 12-month-old infants, for example, can successfully distinguish between 1 and 2 crackers as well as between 2 and 3 crackers but not between 1 vs 4, 2 vs 4 or 3 vs 6 crackers (Feigenson, Carey, & Hauser, 2002). The speed of subitizing increases with age (Chi & Klahr, 1975). Svenson and Sjöberg (1983) reported that in 7-year-old children subitizing one extra dot increases response times by about 100ms, while in adults it was only about 30ms. In their study the maximum number of items that could be subitized changed only slightly from 3 items for 7-year-olds to 4 items for adults. P. Starkey and Cooper (1995) reported a larger age-related increase in the subitizing range from 1–3 items to 1–5 items during early childhood (from 2–5 years of age).

2.2.2Individual differences in subitizing ability and its relationship with mathematics

The discontinuity in the RT slope for enumerating numbers of items does not occur at the same point for all participants (Jensen, Reese, & Reese, 1950; Trick & Pylyshyn, 1994). There is some evidence that individual differences in subitizing in 4- to 6-year-olds are related to the development of their counting skills (Benoit, Lehalle, & Jouen, 2004; Kroesbergen, van Luit, van Lieshout, van Loosbroek, & van de Rijt, 2009; Soto-Calvo, Simmons, Willis, & Adams, 2015). However, subitizing speed in 6- to 7-year-olds did not predict performance in symbolic number comparison or in a number line task, where participants are asked to place numbers on a blank number line (Penner-Wilger et al., 2009). Several studies (Ashkenazi, Mark-Zigdon, & Henik, 2013; Landerl, 2013; Schleifer & Landerl, 2011) reported a deficit in subitizing in children with developmental dyscalculia, a difficulty in the acquisition of number processing and arithmetic (see Chapter 6 for more details). Similarly as for typically developing children, response times for children with dyscalculia also showed a discontinuity between the subitizing and counting/estimating range, but children with dyscalculia seemed to have steeper subitizing slopes than typically developing children (Schleifer & Landerl, 2011). In line with this finding, Moeller, Pixner, Kaufmann, and Nuerk (2009) reported atypical eye-movement patterns in two boys with dyscalculia when enumerating a visual display within the subitizing range.

2.2.3Theoretical models of subitizing

As described above, there is clear evidence for a discontinuity in response times depending on set size when enumerating objects. However, ov...