![]()

PART I

Introduction

![]()

1

A GENDER BOX ANALYSIS OF FOREST MANAGEMENT AND CONSERVATION

Carol J. Pierce Colfer, Marlène Elias and Bimbika Sijapati Basnett

Why this book?

When gender is mentioned in forestry circles, questioning looks of confusion are sometimes the response. Most foresters have been trained—for a very long time—to focus on trees. But there has been a growing recognition in some circles that women and men make different use of trees and have different knowledge and preferences about them. The facts that forests are made up of plants and animals other than trees and can be used for purposes other than timber are increasingly recognized in the field, one that has also encouraged greater attention to gender, as, in many areas, women are more likely to use non-timber forest products and are the primary collectors of fuelwood and charcoal. The physical burden of such collection affects women’s health and reduces the time available to devote to other activities. Ignoring the crucial role that gender relations play in forestry not only undermines local resource conditions, it also prevents women and girls from realizing a full range of their capabilities.

We have produced this book in response to an expressed need for case materials and cross-site analyses on gender issues in forested contexts. Our own institutions are pressured to improve their record on gender in natural resource contexts; our scientists show willingness but repeatedly ask for help. Colfer conducted a survey of 150 experts in forestry-related fields, from a variety of countries and institutional contexts in August 2014, asking what sorts of materials would respond to their need for additional materials on gender and forestry. The most popular format (with 39 percent of the responses) was “an edited collection of academic analyses focused on the tropics.” This book represents our response to this expressed need.

We have assembled a diverse group of authors, from varied backgrounds. The forty authors represent fifteen nationalities, nicely scattered geographically: Africa (three countries), Asia (two), Latin America (three), North America (two) and Europe (five). We also have a broad disciplinary spread, including experts in the social sciences (anthropology, geography, economics, government/policy analysis), natural resources (forestry, ecology, animal sciences), animal and human nutrition, English, and American Indian and Women’s Studies. This diversity shows that a gender lens is not confined to specific disciplines, but can be applied within and across disciplinary boundaries.

We strove to include gender analyses by (and of) men in this collection. We believe we have managed to address gender relatively equitably in our analyses; but we have failed to obtain a good gender balance among our authors: 32 are women, 8, men—with men in no case serving as first authors. This imbalance sadly reflects the persistent, uneven interest in gender as a subject of study.

Our analyses range in scale from intra-household and community through landscape and country-specific studies to regional/global comparisons and reviews. Detailed analyses are provided on gender and forestry issues in 18 countries, 16 of which are in the Global South. Our aim is to converse and connect across countries and contexts; demonstrate that processes taking place in the developed world may not be as dissimilar to those in the developing, and vice-versa, and encourage readers to identify overlaps between seemingly distinct countries and contexts.

We begin here with a brief analysis of the materials themselves, using the Gender Box (Colfer and Minarchek 2013) as an organizing framework. One purpose of the Gender Box was to contribute to the perceived shortage of expertise on gender issues; another was to reflect the topics that gender and forestry specialists have examined and found to be important in maintaining and/or enhancing human and forest well being. Here we examine the topics covered in this book, as they relate to those identified as important in the framework.

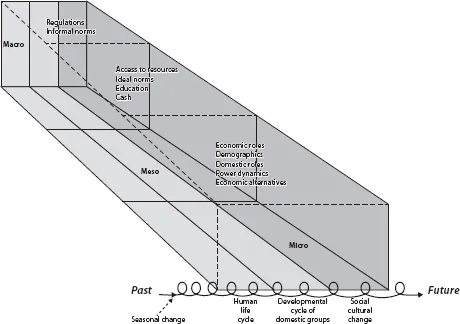

Gender Box analysis

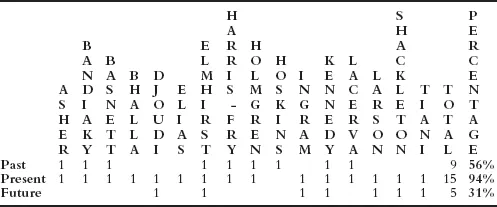

The Gender Box (Figure 1.1) is a three-dimensional figure composed of eleven issues, three scales (micro, meso, macro), and a time dimension. It was designed to serve as a mnemonic device to remind us of the influences of these key issues—scale and time—in our attempts to address gender in forestry. The key issues emerged from extensive reviews of the literature, identifying how gender was being addressed. We recognize that the boundaries between scales (micro, meso and macro) and between times (past, present and future) are fluid and fuzzy. Both represent continua more than discrete categories and they mutually interact. Still, we have found this framework helpful in comprehending the elements that influence gender in specific places. Our ex-post analysis presents the attention devoted to each of these dimensions in the corpus of materials in this book. One purpose has been to highlight the areas that are being well-covered by researchers; another has been to identify other issues that might warrant inclusion in an evolving Gender Box.

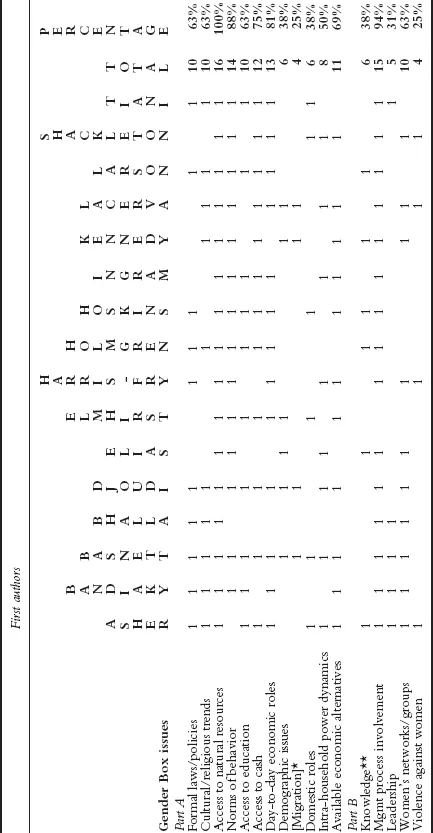

Table 1.1 presents the simple frequencies, indicating which chapters included significant discussion of which issues.1 The table includes a Part A, which focuses on the original issues mentioned in the Gender Box, and Part B, which identifies possible additional issues, based on the discussions in these chapters. The cells are marked with 1 when the issue, scale, or time is addressed, and left blank, if not.

Looking first at Part A in this corpus of material, the dominance of issues like access to natural resources (addressed in 100 percent of the chapters), day-to-day economic activities (81 percent), access to cash (75 percent) and available economic alternatives (69 percent) is unsurprising. These are the kinds of topics on which much gender research across various disciplines has focused. The fairly high proportion of chapters that address the following issues is both surprising and encouraging: Norms of behavior (88 percent), formal laws/policies, cultural/religious trends and access to education (all 63 percent). This suggests a broadening of interest in the research community, a recognition of the holistic nature of people’s lives (including those living in and around forests), and a growing understanding of interactions between scales; for instance, as norms are nested in, influence and are influenced by formal policies.

The lesser attention to intra-household dynamics (50 percent) may reflect the challenges involved in studying these and the difficulty of making policy-relevant recommendations based on such studies. The lack of focus on domestic roles and demographic issues (both 38 percent) reflects in part the fact that many in natural resource fields have not until recently recognized their relevance (as with household dynamics). However, these latter issues are more fully addressed in fields like demography and health, reflecting in this case also a lack of dialogue across disciplines. Where much gender research in the past has focused on exactly what men and women do, men’s and women’s relationships have been found to be central to making desirable and equitable change. The significance of domestic roles and demographic/reproductive matters pertain most fundamentally to the high demands on women’s time, which compete with their time available to pursue own-account, forest-related activities. We need to address such time pressures if women are to play equal roles in such spheres as education, employment, community action and conservation.

TABLE 1.1 Gender Box analysis: issues by chapter

*Migration has been extracted here from the total “Demographic issues” to show its preponderance in the data.

** Potentially relevant for “Access to education,” but focused more on indigenous/experiential knowledge.

We highlighted migration (25 percent) within Part A’s demographic issues (total, 38 percent), because of its increasing incidence worldwide and its influence on gender relations as well as agriculture and natural resource management, which are becoming progressively more feminized. We remain a bit perplexed at the reluctance of many gender and forestry researchers (among others)2 to address population issues—indeed, only one chapter addressed population growth. This seems odd, given the implications of childbearing and rearing for women’s (and men’s) lives and women’s roles on the one hand, and the relevance of population pressure and growth for forest maintenance on the other.

On the whole, there is a good match between the key themes of the compilation and those covered in the Gender Box and listed in Table 1.1, Part A. Part B— representing topics not initially covered in the Gender Box—suggests how the Gender Box can be expanded to better reflect issues of current relevance and interest in the fields of gender and forestry. As shown, involvement in management processes (94 percent) and women’s groups and social capital (63 percent) are common topics, with the related issue, leadership, addressed in 31 percent of our chapters. Knowledge(s), which differ by gender, were addressed in 38 percent of the chapters. The recognition that women and men typically hold distinct and overlapping sets of knowledge and perceptions—much experiential and/or indigenous—is the basis for many other analyses and for engaging with, and hearing from, both women and men during research and management processes.

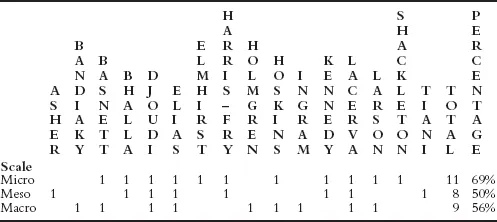

Table 1.2 indicates the scales addressed in these papers (identified by first author; some articles addressed multiple scales). These authors have examined issues across scales fairly evenly (see Colfer et al. 2015: 80 percent of the IFR papers on gender and agroforestry focused on the meso level, with 30 percent addressing each of the other two scales).

Table 1.3 shows the periods of time addressed in each article (again, some articles addressed multiple time periods). Although the present is the most consistently addressed period, there is a fair amount of attention addressed to the past (56 percent) and the future (31 percent). Again, this differs from the focus of the IFR collection on gender and agroforestry, where all authors looked at the present, 30 percent to the past and 10 percent to the future.

TABLE 1.2 Gender Box analysis: by scale

TABLE 1.3 Gender Box analysis: by time

We are encouraged by the wide span of topics covered—which continue to expand as the field of “gender and forestry” gains maturity—as well as the attention to the various scales and the widespread adoption of a historical perspective to inform research on the present and visions for the future. This represents a growing recognition among researchers of the interconnectedness of people’s ways of life (both in terms of issues and scales of action), the influence of history, and the relevance of ideas about the future in shaping current tree use and management strategies.

Introduction to chapters

This book is organized as follows: in Part I, this introduction is followed by a retrospective on gender and forestry by Marilyn Hoskins, one of the grandes dames of gender and forestry. Hoskins led the work of FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) on community forestry—one of the first of its kind—for twelve years, beginning in 1984. She tells a fascinating tale, documenting the early and then-new understandings of women’s roles in forestry and in forests. The chapter highlights a number of troubling issues that sadly remain today, despite significant progress (in which Hoskins has played a crucial role).

Part II turns to climate change, and is followed by Part III and Part IV on tenure and value chains, respectively. As discussed below, we focus on these three central themes because of their timeliness and the significance of these issues—and of gender within them—to forestry research for development. In Part V, three chapters cover a potpourri of longstanding and emerging issues in gender and forestry research; a brief conclusion follows.

It is worth noting that there is an element of arbitrariness about the thematic division of chapters. People’s lives are interconnected, and climate change issues can be affected by tenure and vice versa; value chains, similarly. Any given chapter may well include information about other (or even all) sections of the book.

Part II: Gender and climate change

Nations all over the world are trying to prepare for, mitigate and cope with climate change. Forest-based policies and schemes to mitigate climate change, such as REDD+, have received considerable attention, yet there has been little concern for gender in related deliberations and actions. Terry’s collection (2009) is a valued exception. The seven chapters here represent a needed update. Their approaches vary enormously, ranging from Kennedy’s focus on the perspectives of a small number of elderly women in upstate New York, in the US, to an international comparison of local-level responses to REDD+ implementation in six tropical countries. We begin with two chapters on the Global North for two reasons: first, placing them adjacent to each other made sense, as the issues in these parts of the world differ somewhat from those in the Global South; and second, because we wanted to introduce early on two kinds of issues: the significance of people’s non-monetary values in their decision making and the power of implicit values in policy narratives. These issues are central to shaping forest management processes, but they have rarely been dealt with in the gender and forestry literature.

In recognition of the importance (and frequent dismissal) of values in forest management, we begin with Kennedy’s moving chapter, which focuses on the views of 14 older women (another group often dismissed) from rural and forested areas in New York State. Early on in her chapter, she interrogates two views of gender itself (that of Butler and of Colfer) in ways that should interest and inform our readers. The chapter, rich in its explication of conservation-related values and their bearing on climate change, builds on her two years of continuing interactions with these owners of forested lands. As the director of an NGO, she has worked to codify and formalize “conservation easements” for lands the women are donating to the State of NY for conservation-oriented management “in perpetuity.” For this analysis, Kennedy worked closely with the women to understand what motivates their approaches to conservation and how these relate to climate change. She beautifully weaves in the women’s narratives about their feelings and their commitments to conservation of their lands. In this way, she is able to address the difficult topic of values in a manner that, we imagine, will “speak” to many from diverse cultural backgrounds—despite the acknowledged homogeneity of her sample. Her ultimate argument is that land ethics are an essential backdrop to legal protections, which, as she demonstrates for a nearby Apache (American India...