eBook - ePub

The Afrocentric Praxis of Teaching for Freedom

Connecting Culture to Learning

- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Afrocentric Praxis of Teaching for Freedom

Connecting Culture to Learning

About this book

The Afrocentric Praxis of Teaching for Freedom explains and illustrates how an African worldview, as a platform for culture-based teaching and learning, helps educators to retrieve African heritage and cultural knowledge which have been historically discounted and decoupled from teaching and learning. The book has three objectives:

- To exemplify how each of the emancipatory pedagogies it delineates and demonstrates is supported by African worldview concepts and parallel knowledge, general understandings, values, and claims that are produced by that worldview

- To make African Diasporan cultural connections visible in the curriculum through numerous examples of cultural continuities––seen in the actions of Diasporan groups and individuals––that consistently exhibit an African worldview or cultural framework

- To provide teachers with content drawn from Africa's legacy to humanity as a model for locating all students––and the cultures and groups they represent––as subjects in the curriculum and pedagogy of schooling

This book expands the Afrocentric praxis presented in the authors' "Re-membering" History in Teacher and Student Learning by combining "re-membered" (democratized) historical content with emancipatory pedagogies that are connected to an African cultural platform.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Afrocentric Praxis of Teaching for Freedom by Joyce E. King,Ellen E. Swartz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

“Re-membering” More

. . . the good of all determines the good of each. Seek the good of the community and you seek your own good. Seek your own good and you seek your own destruction.

Kwame Gyekye, An Essay on African Philosophical Thought: The Akan Conceptual Scheme, 1987, p. 20

One arrives at an understanding and rapprochement by accepting the agency of the African person as the basic unit of analysis of social situations involving African-descended people.

Molefi Kete Asante, An African Manifesto, 2007, p. 105

In a previous volume, “Re-membering” History in Student and Teacher Learning: An Afrocentric Culturally Informed Praxis (King & Swartz, 2014), we presented an approach to recovering historical content that entails “re-membering” or reconnecting knowledge of the past that has been silenced or distorted. In the current volume, we broaden this approach to include emancipatory pedagogy in an expanded Afrocentric praxis called Teaching for Freedom. Developed within the Black intellectual tradition, this freedom praxis combines “re-membered” (democratized) historical content with emancipatory pedagogy that has been “re-membered” or put back together with African worldview and the cosmologies, philosophies, and cultural concepts and practices of African and Diasporan Peoples (Abímbólá, 1976; Anyanwu, 1981; Karenga, 1999, 2005a & b, 2006a; Gyekye, 1987). By locating pedagogy within an African cultural context, Teaching for Freedom views educating children as a shared responsibility to enhance community well-being and belonging (King, Goss, & McArthur, 2014). To explore this concept of shared responsibility, we begin with African worldview—a framework that maintains the concepts, ethical teachings, and cultural continuities upon which Teaching for Freedom is built.

African Worldview

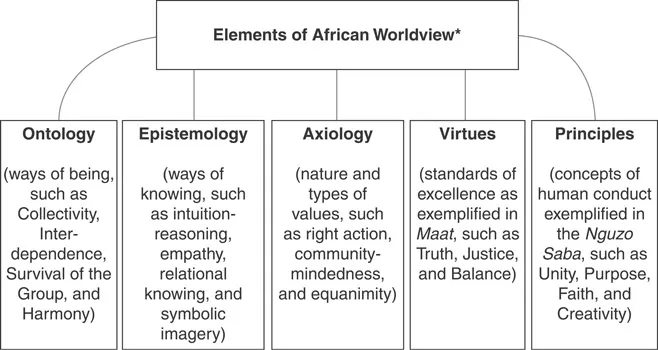

Worldview is a cultural framework shaped by specific ontological and epistemological orientations, axiological commitments, virtues, and principles that endure across time, with each of these elements bearing influence on all phenomena that people who share a cultural heritage produce. Culture—which is an integrated pattern of knowledge, values, assumptions, and social practices—is situational, and differences exist among diverse African peoples—then and now, including the Diaspora. However, the frequency of common concepts, values, assumptions, and practices reflects the underlying unity among these groups and suggests how cohesive cultural factors appear and have been retained across time and geographical location (Anyanwu, 1981; Gyekye, 1987, 1997; Hazzard-Donald, 2012; Idowu, 1973; Konadu, 2010; Mbiti, 1990; Nyang, 1980; Obenga, 1989; Tedla, 1995). Thus, African Diasporan philosophies, cosmologies, and cultural concepts and practices that shape the Afrocentric praxis of Teaching for Freedom are outcomes produced by people who share an African worldview. For example, sharing responsibility for communal well-being and belonging—as a cultural concept of educating children—is one of these outcomes. The five elements of this African cultural framework are shown below in Figure 1.1, with the following descriptions of each element.

- Ontology is the study of being, of what existence and human relationships look like in particular cultural contexts. In African ontology, the nature of existence includes Collectivity (the well-being of the group supersedes the needs of individuals who benefit because the group benefits), Cooperation, Collective Responsibility (everyone contributes to the well-being of the group), Wholeness (all life viewed as one interconnected phenomenon), Harmony (a natural rhythm and movement that exists among all living things), and Interdependence that together speak to the interconnectedness of all forms of life as seen in commitments to human welfare and social, spiritual, and planetary equilibrium (Anyanwu, 1981; Deng, 1973; Dixon, 1971; Karenga, 2006b; Myers, 2003; Nobles, 1985, 1991, 2006; Waghid, 2014).

- Epistemology is the study of ways of knowing and conceptions of the nature of knowledge that also vary across cultural contexts. Along with authority, empiricism, logic, and revelation, African epistemology includes relational knowing (learning from reciprocal interactions), empathy, intuition-reasoning (learning from heart-mind knowledge, which are linked not separate), divination (a learned discipline of decision making based on integrated knowledge from the spiritual, scientific, and unseen worlds), and symbolic imagery

Figure 1.1 Elements of African Worldview.

Note

* Throughout this volume, ontological orientations, Maatian Virtues, and Nguzo Saba Principles are capitalized, but epistemologies and values are not. The former have been identified by scholars cited herein as “the” elements of specific sets of ontological orientations, virtues, and principles; the latter are selected by the authors among many possible examples of epistemologies and values.

- (use of proverbs, gestures, rhythms, metaphors, and affect) (Abímbólá, 1976; Dixon, 1971, 1976; Gyekye, 1987; Ikuenobe, 2006; Nkulu-N’Sengha, 2005). Several of these epistemologies are seen in Diasporan expressions as described in Wade Boykin’s (1983, 1994) African American Cultural Dimensions (e.g., Spirituality, Orality, Verve, Movement, Communalism). In these epistemologically informed cultural continuities, speaking and listening are experienced as performance, cognitive and affective expressions are linked, and sharing and lively interactions and interrelatedness characterize knowing and being with others (Anyanwu, 1981; Boykin, 1983; King & Goodwin, 2006; Nkulu-N’Sengha, 2005; Senghor, 1964).

- 3. Axiology is the study of the nature and types of values—especially in ethics—that also vary across cultural contexts. As seen in African and Diasporan oral and written literature, African axiology reflects commitments to community mindedness, service to others, human welfare, right action, equanimity, and the sacredness of both the spiritual and the material (Anyanwu, 1981; Foster, 1997; Gyekye, 1987; Karenga, 1980, 2006b; King et al., 2014; Sindima, 1995; Tedla, 1995).

- 4. Virtues refer to standards of excellence as exemplified by those found in the Kemetic spiritual and ethical practice of Maat in which disciplined thought of the heart-mind leads to right relations that bring good to family, community, and self through living by its Seven Cardinal Virtues of Truth, Justice, Harmony, Balance, Order, Reciprocity, and Propriety (Asante, 2011; Ashanti, 2008; Karenga, 2006b).

- 5. Principles refer to comprehensive concepts and practices of human conduct, such as those expressed in the Nguzo Saba or Kwanzaa Principles (Unity, Self-Determination, Collective Work and Responsibility, Cooperative Economics, Purpose, Creativity, and Faith). This body of Principles, which are celebrated in the African American holiday Kwanzaa, were drawn from consistent patterns of African thought and practice to affirm and guide the development of African families and communities throughout the world (Asante, 2009; Karenga, 1998, 2005a).

Heritage Knowledge and Cultural Knowledge

Heritage knowledge refers to group memory, a repository or heritable legacy that makes a feeling of belonging to one’s people possible (Clarke, 1994; King, 2006). All cultures have heritage knowledge, which “holds” the cultural legacies and patterns produced by worldview that inform what is taught and how it is taught. For African Americans, this birthright is embodied in knowledge of shared African Diasporan cultural continuities, such as mutuality, spirituality, service to others, justice, and reciprocity. These cultural continuities can be seen in past and present forms of community building that include, for example, adaptive familial structures, mutual aid societies, churches, economic cooperatives, social movements, Freedom schools, and Kwanzaa; and in the relentless collective pursuit of human freedom understood as inherent and present even though denied (King & Goodwin, 2006; King & Swartz, 2014). The Afrocentric praxis of Teaching for Freedom makes it possible for all students to experience belonging in continuity with their ancestral heritage by creating instructional opportunities for them to build on and expand their heritage knowledge. For students of African ancestry, this means that they can use African Diasporan cultural continuities, such as communal responsibility and service to others as contexts for learning.

Cultural knowledge is knowledge gained about the cultural legacies and patterns in cultures other than one’s own. When teachers learn and use cultural knowledge to plan and teach lessons in the social studies and other disciplines, the content and pedagogies they select center students by drawing upon the history and heritage of all students in general and the students they are teaching in particular. For example, we show in Chapter 3 how Harriet Tubman’s African understanding of freedom was at the core of her response to enslavement. When teachers have this cultural knowledge, they can preserve the cultural continuity that is typically severed when figures like Tubman are lifted out of the context of their communities and cultures as special individuals who did extraordinary things. Of course Harriet Tubman was special, but keeping Tubman anchored in her cultural heritage and what it taught her explains so much more about who she was and why she acted as she did. All students benefit from this contextualized presentation of Tubman, and her story is a platform on which students of African ancestry can stand to experience the continuity of their African Diasporan legacy. In terms of pedagogy, when teachers know about the communal values and ways of being and knowing that African people such as Tubman retained in the Diaspora, they understand the logic of building a classroom community and authentic relationships with students and parents, providing opportunities for collaboration and for oral and affective expression, and building on what students know. In these ways, all students can benefit from teachers’ access to cultural knowledge—from content and pedagogy that permit them to learn about diverse histories, legacies, and the worldviews that shape people’s assumptions, ideas, and actions. Both heritage knowledge and cultural knowledge position students as subjects with agency at the center of teaching and learning.

By using content and pedagogy that draw upon heritage knowledge—and the worldviews students’ heritages reflect—we can provide comprehensive instruction and locate students culturally. This is especially important for students of African ancestry, since over several centuries a massive cultural assault due to the Maafa (European enslavement of African people), colonialism, neo-colonialism, and white supremacy racism, has denigrated all things African. This denigration has occurred to such an extent that Africa’s cultural legacy and African American students’ heritage knowledge must be identified and recuperated, even if they exist and operate unconsciously (Akbar, 1984; Dixon, 1971; Nkulu-N’Sengha, 2005). This is especially urgent today when the African continent remains marginalized geopolitically, Africa’s cultural legacy is omitted in school knowledge, and only crises such as war, famine, drought, and disease in Africa appear to be newsworthy.

It is important to emphasize here that this is a call for teachers at all levels to learn about African worldview and incorporate their heritage knowledge or cultural knowledge through accurate scholarship. In pre-colonial African societies, abundant evidence of Africa’s cultural legacy existed in oral, written, and material forms, some of which we provide in this volume. Scholarship in the Black intellectual tradition continues to recover this legacy, thereby helping educators to design and implement schools and liberating educational interventions in service to students and parents of African ancestry and their communities (Goodwin, 2003; King, 2006, 2008; Lee, 1993, 2007; Madhubuti & Madhubuti, 1994; Maïga, 1995, 2005). The praxis of Teaching for Freedom models the use of this scholarship to identify African heritage knowledge, develop cultural knowledge, and consciously locate all students at the center of the learning experience as actors who have the knowledge, skills, and agency to produce academic and cultural excellence, develop good character, and bring just and right action into the world (Karenga, 1999, 2006a & b; King, 2006; Tedla, 1995). In this model, teachers and students are unfettered by coercive pedagogies and limited knowledge that omit or distort diverse ways of knowing and being; and they have opportunities to experience and implement African-informed values, virtues, and principles, such as community mindedness, right action, Reciprocity, and Collective Work and Responsibility.

Worldview and Freedom

The historical record provides further insight into the relationship between African worldview and practices of freedom that undergird the Afrocentric praxis of Teaching for Freedom. This relationship is seen in the experiences of freedom, justice, and social responsibility practiced in Indigenous African Nations—a relationship that African people have continued in the Diaspora. (See King & Swartz, 2014, p. 53 for a detailed explanation of the use and capping of “Nations” and “Peoples.”) From East to West Africa, justice, rightness, and ethical consciousness have been guiding principles that define[d] and demonstrate[d] unity among philosophies as exemplified in Ancient Kemet and in the Songhoy, Yoruba, Dogon, Bambara, and Akan...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- A Note about the Cover Image

- Foreword

- Preface as Prequel

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction: “Re-membering” More

- 2 Culture Connects

- 3 Harriet Tubman: “Re-membering” Cultural Continuities

- 4 “Re-membering” the Jeanes Teachers

- 5 “Re-membering” Cultural Concepts

- 6 Practicing Cultural Concepts and Continuity

- About the Authors

- Index