- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Budgeting for Public Managers

About this book

Benefiting from the authors' many years of teaching undergraduate and graduate students and practitioners, here is a clear, comprehensive, practice-oriented text for public budgeting courses. Rather than presenting each budgeting concern in mind-numbing detail, the book offers a commonsensical view of public budgeting and its importance to current and future public managers. The text is designed to show readers how managers relate to budgeting and how their actions make a difference in the operation and performance of public organizations. The book covers the historical development of public budgeting, sources of public revenues, revenue management, budgeting processes and formats, operating techniques, politics within public budgeting, and more. "Budgeting for Public Managers" is concise, clearly written, well illustrated, and grounded in the real-world concerns of public managers. Each chapter concludes with a helpful list of additional reading and resources for readers who want to dig deeper into budgeting practice and application.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

Introduction

Public Budgeting for Public Managers

A Practical Approach to Public Budgeting

This book differs from most other public budgeting texts by not focusing primarily on budgetary politics, budgeting reform, or federal budgeting. It focuses on how public budgeting relates to what public managers do. Here, a public manager is a person who exercises discretion in supervising the work of a public organization. By contrast, an executive is an elected or appointed official who engages in policy-making, as do board members and legislators. Managers at the upper levels of public organizations, often referred to as administrators, supervise other managers and interact more with policy-makers.

Public Budgeting Defined

Public budgeting means the acquisition and use of resources by public organizations. Acquisition of resources means finding and obtaining useful things, mostly money. For the most part, public organizations in the United States find resources in the private sector; they obtain these resources as taxes, fees, or gifts. Use of resources refers to how resources are spent to achieve public purposes. Resources can be spent on contracts to provide services, to provide direct funding to individuals and organizations, or to purchase input factors, such as labor, capital improvements, supplies, and equipment. the use of resources also refers to the purposes, ends, and functions of public organizations, such as education, public health, criminal justice, art appreciation, and safe travel. public organizations pursue myriad purposes, ends, and functions that define their meaning. For example, the Scleroderma Foundation concerns itself with research, education, and support related to a chronic connective tissue disease.

Public managers acquire access to resources so that they can spend them by gaining policy-makers’ approval of budget proposals. Policy-makers determine generally how resources are used by what they formally approve and by their informal guidance, and managers specifically determine how resources are used by their decisions responding to particular situations.

The Two Sides of Budgeting

Acquired resources are called revenues, and resources being used are called expenditures. Generally, public organizations deal with revenues and expenditures separately, which contrasts with how they are handled in the private sector.

Private sector revenues and expenditures relate closely and clearly. Expenditures are directly associated with production of a good or service for sale. The sale of products generates revenue. AS a result, private sector enterprises expend most of their resources on the products and services that are most directly related to the production of revenues.

Expenditure and revenue decisions in the private sector are relatively simple. Revenues are determined by the number of units of a good or service that are sold and their selling prices. Expenditures are the resources purchased to produce products: for example, labor, capital, equipment, and land. the difference between revenues and expenditures is profit or loss. A number of factors complicate this simplistic description, but the basic points are accurate.

For the public sector, the relationship between revenues and expenditures is often neither close nor clear. Public organizations’ revenues and expenditures mostly operate separately. Governments obtain revenues largely from taxes that are imposed on individuals and business. Specific tax revenues have little relationship to specific expenditures. For example, when federal officials evaluate how much to spend on national defense, the debate centers around external threats to national security, previous expenditures, and anticipated costs. When federal officials look for resources to support defense and other expenditures, they focus on how much revenue to gather to support total expenditures. Those revenue sources have little to do with the production of national defense products and services.

In the private sector, the price mechanism determines what products are produced. In the public sector, policy-makers mostly decide the kinds and levels of revenues and expenditures separately. policy-makers express those decisions in budget documents. Governmental fees for such things as toll roads and entrance to national parks most closely mirror private sector price mechanisms. However, even where fee-for-service operations exist in public organizations, the fees often reflect only a portion of the actual expenditures for particular services.

The Public Budgeting Process

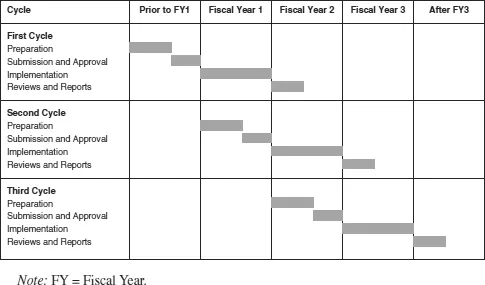

The public budgeting process can be divided into four general stages that occur sequentially: preparation, submission and approval, implementation, and reviews and reports. The four stages constitute a cycle from a beginning to an end with the stages following each other during distinct time periods, although some activities from each of the stages may overlap into following stages. Each cycle is named for the time period of its implementation, which is usually one year in length: for example, Fiscal Year 2015. Each budget cycle always overlaps at least two other budget cycles that are at different stages. For example, the implementation stage of one budget cycle always overlaps the reviews and reports stage of the previous budget cycle and the preparation stage of the succeeding budget cycle. Sometimes public managers work with three or four different budget cycles at the same time. Figure 1.1 shows a fairly typical pattern of overlapping budget cycles. Notice that the implementation stages follow each other.

The preparation stage formally starts when someone begins working to produce a budget for an upcoming fiscal year. Usually, a central office or central official creates and communicates a calendar of budgeting events, budget instructions, and perhaps preliminary revenue and expenditure estimates for the upcoming fiscal period to others in an organization. The instructions require managers to produce estimates of expenditures, usually in some specific degree of detail. Sometimes managers also estimate the likely results of the expenditures or revenues related to their operations.

Managers’ budget proposals are mostly words and numbers indicating the costs of providing services. Administrators, executives, or both review those budget proposals and decide whether they approve each proposal. Unapproved proposals are revised. Eventually, a top-level executive or administrator produces a comprehensive budget proposal for a public organization. Comprehensive budget proposals usually contain estimates of revenues and expenditures, perhaps along with a general policy statement. Although some authors, policy-makers, and public managers emphasize managers’ expenditure-estimating role in budgeting, managers remain active throughout the budget process.

The submission and approval stage starts when a comprehensive budget proposal is submitted to a policy-making body. This stage centers on policy-makers. They examine the comprehensive proposal and gather related information from formal and informal contacts with managers and other interested parties. policy-makers usually discuss budget proposals in one or more meetings and may make changes in a proposal before formally approving it. The time and effort required for approval of a comprehensive budget proposal vary widely among public organizations. Managers often adapt their budget proposals to this stage because gaining approval is required to make a budget proposal an expenditure reality. Changes in a comprehensive proposed budget are usually relatively minor compared to its overall size. This stage ends when policymakers finish approving a comprehensive budget proposal.

Figure 1.1 Overlapping Annual Budget Cycles

Note: F Y = Fiscal Year.

The implementation stage starts when one or more central officials undertake actions to put an approved budget into effect. Managers, start your budgets! A key first step is communicating expenditure authority and any revenue-raising instructions. Some central official or office communicates expenditure authority to the highest level of managers in the operating units, perhaps with restrictions, and they in turn communicate expenditure authority down the organizational hierarchy, probably with restrictions. Although most revenue is collected from ongoing revenue programs, some budget approvals include revenue-raising instructions that a central official communicates to the appropriate places, which might be a central revenue-collecting entity or particular operating units that collect revenues. Then, managers supervise collecting revenue, making expenditures, and recording information on both. Although many authors, policy-makers, and public managers seem to believe that this stage is merely mechanical or clerical as managers follow the great ideas set forth for them by policy officials or high-level administrators, managers at all levels influence high-level administrators and policy officials into forming their great ideas, and public managers may ignore their organizational superiors to some degree in implementing budgets. Managers have a much greater range or degree of discretion in this stage than is generally understood. Otherwise, why are there so many public managers? If budget implementation were mechanical, robots could implement budgets. This stage ends when the collecting and spending stops.

The reviews and reports stage involves various people looking at a budget year to see what can be learned, and producing required and perhaps optional reports in connection with or independent of reviews. parties internal and external to an organization conduct reviews. External reviews usually involve someone outside an organization conducting a review in a highly formal fashion to answer one or more specific questions in a written report. Internal reviews involve people within an organization or organizational subunit conducting reviews of a budget year in an informal fashion to answer the general question of what can be learned by looking at that budget year or specific questions; many such reviews are not reported on in any official fashion. Additionally, public organizations also generate reports, frequently required or expected, that are completely independent of reviews or that are intended to be the basis of reviews. Reviews and reports of past budgets may provide useful guidance for later ones. Examples of reviews include external financial audits conducted by accountants who examine annual financial reports from accounting systems to determine if accounting rules were followed and if financial statements reflect the financial condition of the organization, and informal reviews of a budget year by public managers concerning their own area of responsibility. Annual reports intended as a means of informing the public of the valuable public services provided by a public organization may be essentially free from an internal review process, but they may be the basis for reviews by others using the information provided.

Multiple Budget Documents

People often refer to “the budget” of a particular public organization as if that term referred to one specific document. The proper use of the term “budget” refers to the acquisition and use of resources generally and to a wide array of documents created and used in the various stages of the public budgeting process; no one document is “the budget.” Knowing about the wide variety of different budget documents helps in understanding budgeting activities. Here, some common budget documents are described. The specific details of many of these documents vary greatly depending on their audiences.

During the preparation stage, central offices or officials produce documents meant to inform and guide others, and operating units prepare more detailed documents. A budget calendar shows a schedule of activities, often with deadlines and responsibilities. A call or call letter instructs managers how to prepare and present proposed budgets. A manager of an operating unit creates an expenditure proposal and perhaps a revenue estimate for revenues collected by that unit. Managers incorporate operating unit expenditure proposals and any revenue estimates into ever more comprehensive proposals that eventually become a final proposal. Meanwhile, a central office or official makes calculations for one or more documents showing estimates of general revenues, and operating managers may produce one or more revenue estimate documents relative to their operations; revenue estimate documents become incorporated into a comprehensive budget proposal.

During the approval process, an organization’s policy-makers may work on one or many forms of budget proposals, either portions of a comprehensive proposal or competing alternatives. Also, policy-makers’ staff may prepare documents that provide information or analysis. policy-makers record their budget decisions in one or more approved budget documents.

During implementation, each organizational unit relies on at least one document derived from an approved budget document that indicates how resources can be collected and spent. Each organizational unit usually gets monthly or quarterly expenditure reports, and those concerned with the collection of revenues get monthly or quarterly revenue reports.

During the reviews and reports stage, managers produce financial reports, auditors produce audit reports, and managers responsible for reviews may produce other reports. In any case, memorandums and letters may flow before or after the reviews and reports.

Finally, some public organizations use separate capital budget documents for projects and equipment similar to other budget documents because capital items are considered particularly important. “Capital” here refers to long-lasting, expensive facilities and equipment. Such documents may be used in a regular budget process or a separate capital budgeting process. When public organizations deal with capital items separately during regular budget processes, they may use specialized capital item documents for proposing, submitting and approving, implementing, and reviewing and reporting. For example, expenditures on capital items over certain amounts may require separate justification documents. A separate capital budgeting process uses the same sorts of documents as the regular budget process, but only for capital items.

Multiple Participants

Many people and organizations engage in public budgeting processes, usually in typical roles. Here, “role” refers to expected actions or behaviors much like those of characters in plays. The role that a person or an organization plays in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- 1. Introduction: Public Budgeting for Public Managers

- 2. Historical Development of Public Budgeting

- 3. Sources, Characteristics, and Structures of Public Revenues

- 4. Public Budgeting Processes: Annual, Episodic, and Standing Policies

- 5. Politics Within Public Budgeting

- 6. Organizing Concepts for Expenditure Budgets: Formats and Approaches

- 7. Analysis in Public Budgeting

- 8. Routine Operating Techniques in Public Budgeting

- 9. Economic Explanations in Public Budgeting

- Index

- About the Authors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Budgeting for Public Managers by John W. Swain,B.J. Reed in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.