![]()

Chapter 1

Business control and risk management

Good management is the art of making problems so interesting and their solutions so constructive that everyone wants to get to work and deal with them.

–Hawken, 2015

Effective leadership is putting first things first. Effective management is discipline, carrying it out.

–Covey, 2015

A brief history of business control

We’ve no idea how the ancient Egyptians (or someone) built the pyramids, despite watching National Geographic Channel. Massive structures, huge stone blocks moved from hundreds of miles away, great symmetry and cosmic alignment. Many ideas have been suggested (Asbury, 2013, p.48), but there remains little or no certainty.

As Paul Hawkens and Steven Covey reflect, good management certainly concerns prioritizing; making problems interesting and controls constructive. We also know very little about the absolute origins of management systems, but we suggest that the Chinese military General Sun Tzu was one of the first to understand the benefits of structure in control. Certainly, since its translation into the first European language in 1782, his book The Art of War (Tzu, 2009) has been regarded as a masterpiece of strategic thinking. Its significance was quickly recognized; and such towering figures of Western history as Napoleon and General Douglas MacArthur have claimed it as a source of inspiration.

Sun Tzu

The earliest historical record of using a systemic framework for control of an activity and giving some assuredness of consistency of outcome dates back roughly 25 centuries to ancient China. Our suggestion is that the origins of modern management systems go back to the activities and subsequent writing of the military general, strategist and philosopher Tzu. Traditional accounts place him as a military general serving under King Helu of Wu, who lived c. 544–496 BCE. The story of Sun Tzu’s life is based on the following legend:

The King of Wu tested Sun Tzu’s skills by commanding him to train 180 concubines as soldiers. Sun Tzu divided the girls into two companies, appointing the two concubines most favoured by the King as the company commanders. When Sun Tzu first ordered the concubines to face right, they giggled. Sun Tzu said that the general, in this case himself, was responsible for ensuring that soldiers understood the commands given to them. Then, he reiterated the command, and again the concubines giggled. Sun Tzu ordered the execution of the two company commanders (the King’s favoured concubines), even though the King protested. Tzu explained that if the general’s soldiers understood their commands but did not obey, it was the fault of the officers. He also said that once a general was appointed, it was their duty to carry out their mission. After both concubines were killed, new officers were selected to replace them. And afterwards, both companies performed their manoeuvres flawlessly. Managers today can learn much from this story.

General Tzu’s now famous book The Art of War presents a philosophy of war for managing conflicts and winning battles in 385 points set out in thirteen chapters – it is a highly interesting and recommended read. It is accepted as a masterpiece on strategy and is frequently cited and referred to by generals and theorists since its publication, translation and distribution the world over. However, only in recent times (since the mid to late 1950’s), has ‘strategy’ been associated with ‘management’ per se. For two-and-a-half millennia, ‘strategy’ was exclusively used as a military term, and defined interestingly as ‘The Art of War’.

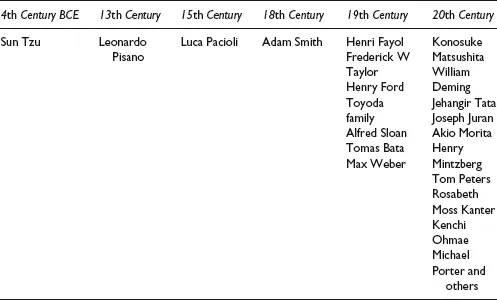

From Sun Tzu to the twentieth century and since, there has been an evolution of management systems thinkers and thinking, and we have summarised some of the main pillars of this in Figure 1.1.

Bringing this evolution of management systems thinking fast-forwards through 2500 years, we (and many others) feel that another significant initiating moment in the evolution of modern business control was from 14 October 1900 in Sioux City, Iowa, USA.

Deming

Dr William Edwards Deming (14 October 1900–20 December 1993) was an American statistician, professor, author, lecturer and consultant. He trained to be an electrical engineer and worked briefly as an engineer in Chicago before becoming a statistician, working in the US Bureau of Census. His Ph.D. was in mathematical physics, awarded by Yale. He is best known for his work in Japan, where he taught senior management how to improve design, service, product quality, testing and sales through various methods, including the application of statistical process control and related methods. His continuous quest for understanding processes and deviations from the norm led him to become one of the founding fathers of the quality movement.

Dr. Deming (Figure 1.2) made a significant contribution to Japan’s later reputation for innovative high-quality products and its economic power. He is regarded as having had more impact upon Japanese manufacturing and business than any other individual not of Japanese heritage. In the years following World War II, Deming was sent to work in Japan. Working with a fellow American, Joseph Juran, he developed production and management theories that later became known as the ‘right first time’ philosophy in Japanese industry. These have been exported around the world since the quality revolutions of the 1980s and 1990s.

We say that ‘management’ is nothing more than motivating other people to deliver what is needed.

(Lee Iacocca (2015), former President and CEO of Chrysler, 1978–1992)

Academics and industrialists credited Deming and Juran with giving birth to an industrial revolution through the way they developed statistical control of quality levels into a new way of managing business.

Dr. Deming was the author of Out of the Crisis (2000a, originally published in 1982) and The New Economics for Industry, Government, Education (2000b, originally published in 1993). The latter includes his ‘System of Profound Knowledge’ and the ‘14 Points for Management’, which we encourage you to review.

In Out of the Crisis, Dr. Deming said:

(Deming, 2000a)

Deming said that once transformed, the individual would:

(Deming, 2000a)

Plan-Do-Check-Act

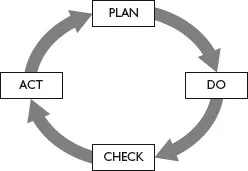

At the heart of Deming’s legacy to the (business) world is the adoption in his teaching of the four steps in the Deming Wheel: Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) also referred to by Deming later in his life as Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA).

In his own writing, Dr Deming actually called this cycle of activities the Shewhart Wheel, after his friend and mentor Walter Shewhart. Whatever it is called, this wheel (or cycle) can be used in various ways, such as running an experiment:

• PLAN (or design) the experiment;

• DO the experiment by performing the planned steps;

• CHECK the results by testing them;

• ACT on the decisions based on those results.

This cycle, commonly called ‘The Deming Wheel’, is shown in Figure 1.3. It was proposed as a cyclical process to determine in a never-ending way the next action, with the ‘Wheel’ illustrating a simple approach to testing information before making a major decision.

The shorthand PDCA mnemonic has borne the test of time despite the efforts of certification bodies, business sector organizations, consultants and academics who have substituted Deming’s simplicity with complexity. PDCA lives at the heart of the latest iteration of ISO management systems based on Annex SL, which you will read about later in this chapter and which has revolutionized ISO 9001, ISO 14001 and other standards recently. It is also commonly applied as a ‘wheel within a wheel’ to illustrate the relationship of operational processes to corporate and strategic processes.

Deming saw that the elimination of waste could be achieved by aligning processes coherently and then carrying them out in a manner which was as close to the laid down standards as they could be – the control of variation, so to say. The armaments and munitions industry was one to see the potential of such an approach to manufacturing, since every time ammunitions failed to explode upon impact, all of the resources that were consumed before launching the weapon at its target had zero payback, since the enemy’s soldiers and equipment had not been destroyed as intended.

For example, some observers feel that the outcome of the Falklands War (commonly known in Argentina as Guerra de las Malvinas) – an effective state of war between Argentina and the UK between 2 April and 14 June 1982 over the long-disputed territories of the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands – might have had quite a different outcome if more of the bombs launched by the Argentinean air force had actually exploded on impact with their British Royal Navy targets. Would these munitions have exploded as designed if they had been manufactured and assembled by Toyota?

Manageme...