“Judeosoc: the Jewish socialists. This is the most dangerous formation of the socialist, our most worst enemy. They are competent and intelligent. Adam Michnik, TVN television, Gazeta Wyborcza daily – this is where they are hidden. They hate me sincerely,” said newly elected Polish member of the European Parliament, Janusz Korwin-Mikke in an interview with Newsweek magazine (Krzymowski, 2014). His declaration represents a specific genre of political communication in which specific ethnic minority is presented as omnipotent, powerful, and realizing its hidden agenda.

Similar statements could be heard in other political campaigns in Poland, making conspiracy theories pronounced within public discourse (Bilewicz, Winiewski, & Radzik, 2012). In this chapter, we would like to explain this mobilizing role of conspiracy theories in times of political change, focusing mainly on the conspiracy stereotypes of Jews that portray this minority as powerful and engaged in evil plots. At the same time, we propose that conspiracy stereotypes are activated in specific situations, although most of the time they remain dormant. We aim at understanding the popularity of conspiracy stereotypes among different social groups – people who are economically deprived and senior citizens – who tend to be most committed to such theories in times of political mobilization. We propose that conspiracy stereotypes respond to particular needs among such groups – they serve explanatory functions and respond to threatened cognitive motivations.

The belief in Jewish conspiracy as a stereotype

Most of the literature on stereotyping focuses on the cognitive character of this process. Thus, stereotypes are social schemas that organize the knowledge about groups and allow the application of such knowledge in the process of categorization (Hamilton, 1981). Stereotypes lead to several cognitive biases in person perception – in information selection, biased attention to stereotype-confirming information, and selective memory (Fiske, 1998; Snyder, 1981). At the same time, stereotypes serve explanatory functions, justifying intergroup inequalities and legitimizing groups’ existence and treatment of specific group members (McGarty, Yzerbyt, & Spears, 2002).

This description applies well to trait-laden stereotypes – social schemas of prototypical group members. At the same time, people often hold representations of certain groups as a whole that differ from the stereotype of a prototypical group member. Such group-level stereotypes often have a form of lay theories, presenting groups as existing entities (Haslam, Rothschild, & Ernst, 2000). Members of entitative groups are perceived as interchangeable individuals bonded with an underlying essence. Such groups become natural kinds, similar to chemical particles, physical elements, or biological species (Keller, 2005). Most psychological research reflects on the biological forms of essentialism (Haslam et al., 2000; Keller, 2005). Research by Kofta and Sedek (1992; 2005) on the stereotype of a group as a whole, later named “conspiracy stereotypes,” is an attempt to study social forms of essentialism, in which group essence is ascribed not as a biological metaphor, but rather as a social lay theory. Although such stereotypes do not offer a schema of individuals, they are often applied in processing information about groups. Conspiracy stereotypes also serve an explanatory role, allowing the creation of lay theories about the social world and offering an interpretation of political events and conflicts.

The original research on conspiracy stereotypes was conducted in the context of the stereotypical perception of Jews in Poland (Kofta & Sedek, 1992; 1995; 1999a; 2005). Such stereotypes form a causal, holistic theory of an ethnic group. It points to alleged collective goals of a group (i.e., striving for power and dominance over other ethnic groups), secret character of collective behavior (i.e., plots, conspiracies, secret agreements), and high levels of group egoism (i.e., support for fellow in-group members combined with a lack of interest in the well-being of other groups). Group members become merely executors of the collective intentions of the group as a whole (Kofta & Sedek, 2005).

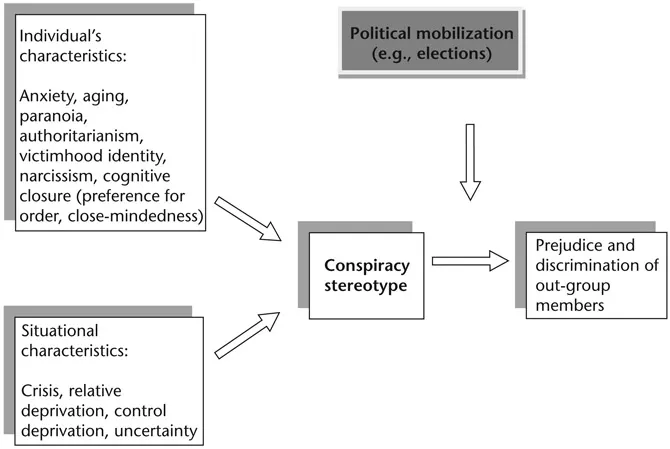

The belief in Jewish conspiracy is a part of the modern anti-Semitic imagery, although its sources can be traced back to the social position of Jews in premodern societies. It has been observed in areas populated by sizeable Jewish minorities, such as Britain (Billig, 1987) or Ukraine (Bilewicz & Krzeminski, 2010), and in countries where large Jewish communities existed in the past, such as Poland (Bilewicz et al., 2012), but also in countries where almost no Jews ever lived, such as Malaysia (Swami, 2012). The existence of conspiracy stereotype of Jews in countries where the target of stereotype is virtually absent raises an important question about the sources of this stereotype, as well as its function in contemporary society. In this chapter, we present a model that aims to explain the antecedents and consequences of conspiracy stereotypes (Figure 1.1). The model suggests that both individual characteristics and objective situational circumstances are responsible for people’s endorsement of conspiracy beliefs. At the same time, we argue that such beliefs are activated by a specific trigger: namely, the situation of political mobilization. Such a situation allows people to translate a conspiracy stereotype into collective action, discriminatory behavior, or prejudice.

FIGURE 1.1 The model of conspiracy stereotyping: antecedents and consequences.

Trait antecedents of conspiracy stereotypes: Between personality and cognition

People who believe in conspiracy are often accused of possessing a paranoid cognitive style and other mild forms of psychopathology. The authors of original research on authoritarian personality cautiously observed: “there is … evidence that can be interpreted as in accord with the possibility of paranoid trends in our subjects extremely high on anti-Semitism” (Frenkel-Brunswik & Sanford, 1945, p. 280). Further research provided mixed evidence about the impact of paranoia (in its clinical sense) on belief in Jewish conspiracies, although certainly the relation of politicized forms of paranoia and belief in Jewish conspiracy is a well-established fact (Korzeniowski, 2009; 2010). In his rigorous studies on the topic, Krzysztof Korzeniowski (2010) found that the link between political paranoia and the belief in Jewish conspiracy holds even after controlling for general social distance towards Jews. People with political paranoia believe in Jewish control over the economy; they perceive Jews as aiming to dominate the world and contracting secret plots. Political paranoia and conspiracy stereotypes have similar correlates: political alienation and authoritarianism (Bilewicz et al., 2012; Korzeniowski, 2009; Swami, 2012). What links paranoid style in political thinking and conspiracy stereotyping is the general perception of threats in one’s social environment.

Early theorizing by Allport (1954) perceived anxiety, insecurity, and fearfulness as a core of the prejudiced personality. Evidence from the studies on intergroup anxiety, as well as on intergroup threat theory, confirms that many of the negative intergroup attitudes are based on fears of either symbolic or realistic character (Stephan & Stephan, 1985; 2000). Conspiracy stereotypes of Jews – forming the grounds for anti-Semitic attitudes – were often linked with anxiety and sense of threat (Ackerman & Jahoda, 1950; Frenkel-Brunswik & Sanford, 1945).

In a recent study of this issue, Monika Grzesiak-Feldman (2013) analyzed the influence of anxiety on conspiracy stereotypes of several ethnic out-groups (Jews, Germans, and Arabs). She found systematic positive correlations between anxiety (both state and trait anxiety) and conspiracy stereotypes of all three ethnic groups. Trait anxiety was particularly linked with beliefs in Arab conspiracy, whereas state anxiety was particularly linked with a belief in Jewish conspiracy. Her subsequent studies (Grzesiak-Feldman, 2013, Studies 2 and 3) confirmed this observation: threatening situations, such as pre-examination stress, increased people’s endorsement of a conspiracy stereotype of Jews. This points to the situational antecedents of conspiracy stereotypes – such as relative deprivation or crises – as potential determinants of state anxiety. Anxiety is also an essential part of an authoritarian personality. Authoritarians believe that the social world is dangerous and threatening (Altemeyer, 1998; Duckitt, 2008). In his integrative model of personality, ideology, and prejudice, Duckitt (2008) showed that high authoritarians express a motivational goal of establishing stability that helps them regain security in a threatening and dangerous social world. Group membership forms a buffer against such threats (see also Fritsche et al., 2013). This leads to out-group prejudice and the maintenance of stereotypes, among them conspiracy stereotypes.

The main aim of the original research on authoritarian personality (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950; Frenkel-Brunswik & Sanford, 1945) was to analyze the psychological bases of support for fascism and anti-Semitic ideologies. Several studies found that authoritarianism, as well as its more modern form of right-wing authoritarianism (Altemeyer, 1998), is a crucial antecedent of conspiracy stereotypes, particularly the belief in Jewish conspiracy (Abalakina-Paap, Stephan, Craig, & Gregory, 1999; Bilewicz et al., 2012; Grzesiak-Feldman & Irzycka, 2009; Korzeniowski, 2010). The influence of authoritarianism on conspiracy beliefs is further discussed by Grzesiak-Feldman and Imhoff (this volume).

The least researched of the individual-difference antecedents of conspiracy stereotypes are the cognitive and motivational influences on judgmental processes across the adult life span. Early survey findings based on a national sample of Polish adults (Polish General Social Survey, 1992) indicated a relatively strong correlation (r = .26) between the age of respondents and conspiracy stereotypes of Jews (see Kofta & Sedek, 1999a, Table 1). Interestingly, a social survey conducted in the United States, the Chicago Area Survey from 1992, in the same year, indicated that both the age of respondents and their level of conspiracy stereotype of Jews were significant predictors of negative attitudes towards Americans of Jewish origin, when partialling out the significant roles of education and political conservatism (Kofta & Sedek, 1999a, Table 4). The more recent studies also indicate that beliefs in Jewish conspiracy are often found to be related with age – senior people are more committed to conspiracy stereotypes than younger cohorts (Bilewicz, Winiewski, Kofta, & Wójcik, 2013; Krzeminski, 2002; Zick, Küpper, & Hövermann, 2011).

This leads to a conclusion that there might be some cognitive and motivational factors responsible for older adults’ endorsement of conspiracy stereotypes. In recent years, researchers have demonstrated that older adults are more likely to stereotype a variety of social groups than younger adults (for a recent review, see Radvansky, Copeland, & von Hippel, 2010; Stewart, von Hippel, & Radvansky, 2009). One of the common explanations for this finding is that older adults find greater difficulty than do younger adults in inhibiting stereotypic thoughts because of a decline in the inhibitory function (e.g., Hasher, Zacks, & May, 1999; von Hippel & Dunlop, 2005; von Hippel, Silver, & Lynch, 2000). Another set of explanations asserts that aging-related limitations in other cognitive functions involved in social information processing (e.g., limitations in mental speed, working memory, or flexibility) constrain the amount and type of information used in constructing judgments (Henry, von Hippel, & Baynes, 2009; Hess, 2000). This reduced utilization of cognitive resources among older adults results in the use of schematic representations, biased judgments about others, and greater social inappropriateness. The recent research (Czarnek, Kossowska, & Sedek, in press) extends previous research by examining both the cognitive and motivational aspects of deficient flexibility, which might be responsible for stereotypic inferences about out-group members among older adults. We hypothesized and found that the motivational mediator between age and the tendency to draw stereotypical inferences about out-groups is the need for closure (NFC) (Kruglanski, 1989). NFC is defined as a need to have any answer on a given topic in order to avoid further ambiguity about that topic. It is well established that a high NFC is associated with a schematic processing style, in which attitudes and judgments are based on schema-related cues rather than on thoughtful consideration. In contrast, low NFC is associated with a systematic processing style, in which attitudes and judgments are based on careful scrutiny and the elaboration of information. We suggested that this motivation, exhibited as a tendency to preserve available resources and engage in activities that minimize any drain on these resources (Kossowska, 2007; Sedek, Kossowska, & Rydzewska, 2014), may play a crucial role in how information is processed in older versus younger adults.

In a recent study, we found substantial support for the predicted mediating role of the need for cognitive closure on the relationship between aging and the level of accepting the conspiracy stereotypes. In this online study, we measured belief in Jewish conspiracy and the need for cognitive closure in a sample of 571 adult Poles from two age groups: 18–25 years old and 50–60 years old. We found that senior Poles express significantly higher levels of conspiracy stereotype than do young Poles. Additionally, we performed a set of mediation analyses in order to test for indirect effects of age on conspiracy stereotypes through different components of need for cognitive closure. The findings of this study support the prediction that the effect of age on conspiracy stereotype is significantly mediated by four subscales of NFC (preference for order, predictability, discomfort with ambiguity, and closed-mindedness).

Overall, these findings might be interpreted in motivational terms (see Czarnek et al., in press; Hess, 2014; Hess & Queen, 2014). According to this motivational account, aging is related to increasing costs of engagement in effortful cognitive activities. As aging proceeds, more resources are necessary to achieve a particular level of performance in an effortful task. Furthermore, perception of costs results in the lack of intrinsic motivation to commit resources to cognitively demanding tasks, and that in turn is reflected in the selection processes of directing and energizing. Hence, older adults tend to invest their very limited cognitive resources in tasks that are important to them and relate to their ever...