1a Monument G as a call for reconstruction

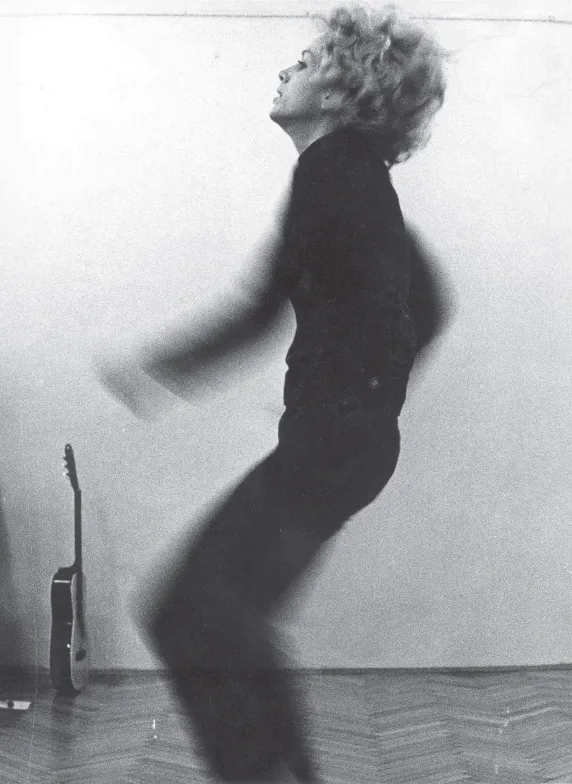

Janez Janša

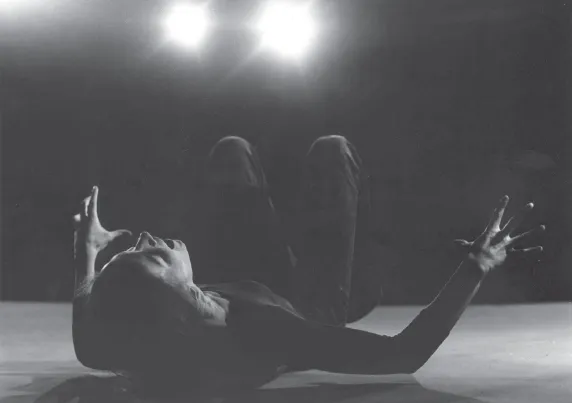

1b Untitled (After Violent Incident)

Tim Etchells

1c Stuart Sherman’s Hamlet: a careful misreading

Robin Deacon

1d Rosemary Butcher: After Kaprow—a visual journey

Rosemary Butcher and Stefanie Sachsenmaier

1e Six questions

Zhang Huan

The ghost time of transformation

Adrian Heathfield

The OED defines the verb REMAKE as to ‘Make (something) again or differently’. It is a term that has associations with remakes of Hollywood movies. Slavoj Žižek writes ‘Is there a proper way to remake a Hitchcock film?’, proposing that there are two approaches to ‘the ideal remake’. Firstly he proposes ‘an exact frame-by-frame’ reconstruction, which takes further ‘Gus van Sant’s strategy with Psycho’ and attempts to shoot ‘formally the same film’ in order to ‘achieve the uncanny effect of the double’. He suggests that ‘on account of this very sameness’ of ‘shots, angles, dialogue’, ‘the difference would have become all the more palpable’ (Žižek 2007: 263). Žižek goes on to suggest that ‘the second way’, which would be preferable to ‘direct “homages”’, would be to stage in a well-calculated move, one of the alternative scenarios that underlie those actualised by Hitchcock’ (2007: 264). For Žižek creation is perceived as a negative gesture of selecting from among multiple virtual versions and thus limiting possibilities. The artists in REMAKE apply both of Žižek’s strategies, often in combination: firstly, attempting to reconstruct formally, whilst explicitly staging the process of copying and doing so in order to produce difference rather than sameness; secondly, calculatedly constructing alternative versions in order to make again differently, thus producing gaps between archival source and remake in which reflection can take place.

As Janez Janša notes below, Monument G, ‘stages the fundamental tension included in every historicization, the tension between history and story, facts and their construction’. In relation to an earlier remake, Puilija, Papa Pupilo and the Pupilceks—Reconstruction (2006), Janša writes that the motive for reconstructing was not to ‘re-experience a performance from the past’ but to experience or watch ‘our relation to history’ in order to question the present, for instance contemporary cultural or ethical positions (Janša 2012: 373). In the case of Etchells’ Untitled: After Violent Incident (2013), this work attempts to produce sameness in another medium, remediating Bruce Nauman’s Violent Incident (1986), a twelve channel video installation, through performance. As two performers try to reiterate the loops of Nauman’s video recordings live, version control fails and becomes impossible to manage, as human error, physical exhaustion and contingencies find their way in and are documented. Violent Incident represents a traumatic domestic event, while drawing on slapstick and clowning. Hal Foster (1996), citing Freud, argues that the subject is compelled to repeat such events ‘in actions, in dreams, in images’, and similarly, Žižek (1991) writes of ‘traumatic encounters’ with film or video, which produce a surplus that ‘propel[s] us to narrate [them] again and again’ (133), to screen or perform them repeatedly.

Robin Deacon’s long-term project, Approximating the Art of Stuart Sherman (2008–14), around the work of the late American artist Stuart Sherman arose out of a formative encounter, when he saw Sherman perform in 1994, at Cardiff School of Art. Deacon suggests that he has ‘a personal investment because of his influence on me’ (Deacon 2009). He specifically notes that the small scale of Sherman’s work ‘really stayed with’ him and ‘from then on all [his] performances were on little tables’, using the tabletop as a stage. Deacon says that he went back to ‘actual documents’ in order to ‘try to do something different with them’ (Deacon 2009) and the title of his Sherman series acknowledges that his remakes are approximations of the artist’s complex tabletop choreographies of objects. His Sherman project also explores ‘the possibility for the preservation of ephemeral artworks through reenactment’ (2013), especially in the case of artists whose work has been marginalised by history, left out of the authorized archival or art historical record and not digitised. Perhaps we might think of this as the return of a culturally repressed work and of practices that left an affective trace in Deacon’s body.

On their pages, Rosemary Butcher and Stephanie Sachsenmaier write around Butcher’s series of choreographic responses to Kaprow’s 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (1959), a work regularly written into art histories as the first happening and the originary event in the emergence of this form. 18 Happenings is a performance that has now inspired multiple versions, including André Lepecki’s redoing for Haus der Künst, München, in 2006, and subsequent iteration for PERFORMA 07, New York. Butcher responds to Kaprow’s will, permission, explicit wish or direction that this work should be performed again and have a future, but, rather than reconstructing with ‘near archaeological accuracy’ (Dorment 2010) from the meticulous documents that Kaprow left in the manner of Lepecki’s redoing, her cycle of new actualizations are reinventions filtered through contemporary aesthetics. As Sachsenmaier remarks, the impetus for Butcher, who sadly passed away in 2016, was to trace her roots and influences in New York, where she worked with members of Judson Church in the late 1960s and early 70s. In the process of reinventing 18 Happenings, by ‘going back’ to Kaprow’s archive, she was able to ‘move her work on’ and to experiment with ways to ‘move dance into a visual [art] setting’.

The final artist’s pages in this section, by Chinese artist Zhang Huan, shift the focus to sculptural objects that are bodily in form and to materials that carry traces of cultural acts. Zhang Huan began by making performance art in Beijing, then emigrating to the US in 1998. In 2006 he returned to China, and focused on the production of sculptures, often rendered on a monumental scale. Zhang’s vast public artworks, such as Three Legged Buddha (2010), both reconfigure and monumentalise the remains of Buddhist relics and the minor histories or unauthorised cultural memories they hold. Rui Lai (2009) is also a reconstructed Buddhist figure, but in this instance it is the material that is remarkable, as it is partially made of ash from incense and burnt offerings, which were gathered from a local Buddhist temple. This material documents the ritual acts that produced it and for Zhang Huan carries forward traces of the personal feelings, blessings and souls with which it was associated. For him found materials and objects are performative and can have a powerful agency that excites him, makes him sleepless and compels him to rework them.

References

2009 Deacon, R. ‘Robin Deacon on Stuart Sherman’. Interview by Rachel-Lois Clapham. Available online. http://www.robindeacon.com/rl_clapham_interview.htm. Accessed 1 March 2017.

2013 Deacon, R. ‘Spectacle: A Portrait of Stuart Sherman’. Available online. http://www.robindeacon.com/spectacle_movie.htm. Accessed 1 March 2017.

2010 Dorment, R. ‘Allan Kaprow’s 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, Festival Hall, review’. The Telegraph, 30 November. Available online. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-reviews/8170048/Allan-Kaprows-18-Happenings-in-6-Parts-Festival-Hall-review.html. Accessed 2 March 2017.

1996 Foster, H. The Return of the Real, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

2012 Janša, J. ‘Reconstruction2: On the Reconstructions of Pupilija, Papa Pupilo and the Pupilceks’. In A. Jones and A. Heathfield (eds) Perform, Repeat, Record: Live Art in History, Bristol: Intellect, pp367–83. 1991 Žižek, S. Looking Awry, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

2007 ‘Is There A Proper Way To Remake A Hitchcock Film’, In S. Brode (ed.) J. Grimonprez: Looking for Alfred, Berlin: Hatje Cantz, pp261–73.