- 156 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

In this new book, you'll learn how to teach evidence-based writing using a variety of tools, activities, and sample literary texts. Showing elementary and middle school students how to think critically about what they're reading can be a challenge, but author C. Brian Taylor makes it easy by presenting twelve critical thinking tools along with step-by-step instructions for implementing each one effectively in the classroom. You'll learn how to:

- Design units and lesson plans that gradually introduce your students to more complex levels of textual analysis;

- Encourage students to dig deeper by using the 12 Tools for Critical Thinking;

- Help students identify context and analyze quotes with the Evidence Finder graphic organizer;

- Use the Secret Recipe strategy to construct persuasive evidence-based responses that analyze a text's content or technique;

- Create Cue Cards to teach students how to recognize and define common literary devices.

The book also offers a series of extra examples using mentor texts, so you can clearly see how the strategies in this book can be applied to excerpts from popular, canonical, and semi-historical literature. Additionally, a number of the tools and templates in the book are available as free eResources from our website (http://www.routledge.com/9781138950658), so you can start using them immediately in your classroom.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

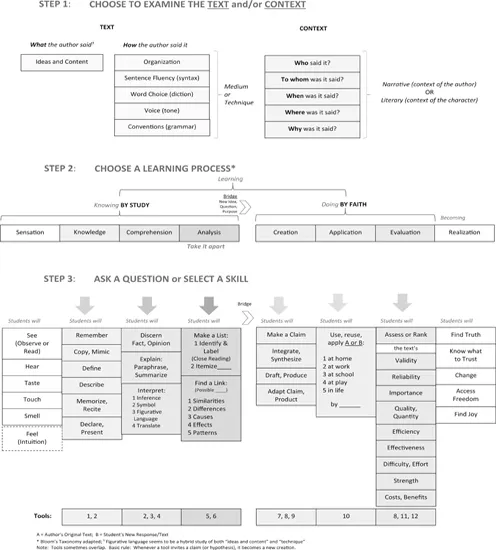

A Critical Thinking Map: Thinking about Text

Step 1: Choose to Examine the Text or Context (or both)

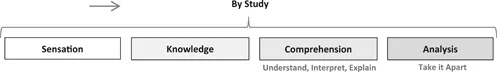

Step 2: Choose a Learning Process

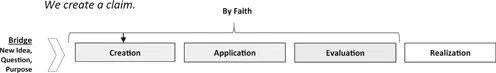

Crossing the Bridge from Knowing to Doing

| Knowledge: | A student at this stage knows the parts of the engine. He or she can look at pictures and match car parts with their names or uses. |

| Comprehension: | A student at this stage can explain how the engine functions. For example, the student can explain how the fuel, mechanical, or electrical systems work independently or together. |

| Analysis: | A student is here when he or she can take apart an engine, list or classify those parts in various groupings. If a car has problems, this student can trouble-shoot by listing possible causes of the problem and what affects it might have on performance. (The moment he or she develops a theory of the problem, that student has crossed the bridge into creation because he/she has formed a hypothesis.) |

| Now the student has a choice to make (crossing the bridge): | |

| Creation: | The student may want to build an engine (by fixing or replicating an old one); rebuild one, possibly with parts or designs from other cars (“integration” or “inter-synthesis”); or invent an entirely new engine. (Innovation may represent the highest form of creation.) |

| Application: | The student may apply his prior knowledge by getting a job as a mechanic, or by working on his or her own car. |

| Evaluation: | The student can evaluate the old engine (from which he/ she learned) or new engine (he/she built), testing either to see if it works correctly (validity) and consistently (reliability). Maybe there’s a way to make the car more fuel efficient or cost effective. If the student-mechanic then offers a recommendation based on this evaluation, then he or she organically returns to "creation" because a claim has been made. |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- eResources

- About the Author

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 A Critical Thinking Map: Thinking about Text

- 2 The 12 Tools

- 3 The Evidence Finder

- 4 The Secret Recipe

- 5 Guided Practice

- 6 Extra Examples Using Mentor Texts

- 7 Bonus Tool: Cue Cards to Teach Literary Terms

- References

- Index