Women are gaining ground as presidents in Latin America. Eight of the 30 women presidents taking office to date hail from this region; half of them have come to power since 2006.1 Despite increasing quantities, relatively few women presidents or prime ministers exist. They exercise somewhat limited powers and emerge from a very narrow array of circumstances, contexts, and backgrounds (Jalalzai 2013). Women are also less apt to become executives in presidential systems.

Quantities of women presidents worldwide vastly increased from the 1990s onwards, corresponding with women’s heightened prevalence to throw their hats in the ring (Jalalzai 2013). Women presidential aspirants, however, rarely finish on top or garner substantial vote percentages, perpetuating male domination of these positions. Women successfully navigating the electoral waters overwhelmingly relied on family ties; their blood or marital connections to former presidents/prime ministers or, more rarely, opposition leaders, minimized traditional barriers women faced in executive politics. Family ties appeared particularly salient within politically unstable contexts. Frequent regime changes resulted in executive posts being more open to challenge, sometimes promoting specific women with family ties to power.

Latin America and Asia began and sustained this trend of women presidents’ dependency on family ties in post conflict/transitional contexts. Women leaders here also often arose through succession rather than popular election. Latin American women presidents were relegated to wives of former presidents or opposition leaders, a pattern first established by Isabel Perón (the first woman president in the world) in Argentina in 1974, and one remaining largely uncontested for over 30 years (Jalalzai 2013). Over the last decade, however,women’s paths to presidential power grew more varied in Latin America, but stayed very limited in South and Southeast Asia (Jalalzai 2013). Women presidents in Africa (with the exception of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia) are glaringly under-represented which is also the case in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.2 This is especially significant since these regions commonly utilize either presidential or semi-presidential systems. Latin American women presidents, therefore, led the way in defying prevailing patterns by increasingly gaining dominant presidencies through popular election within stable political settings. Notably, some completely lacked family connections to power. Why here, why now and to what effect?

The objective of this book is to examine all Latin American women presidents (also referred to as presidentas throughout) to date, and in doing so, answer two main questions. First, what conditions allowed for a broadening of routes for women presidents in these specific locations and at this particular point in time? Second, once in office, dopresidentas use their powers to enhance women’s representation, defined as the combination of factors that result in political leaders acting on behalf of citizens (Pitkin 1967)? I aim to assess the paths and impacts of Latin American women presidents and scrutinize the ways gender shapes both aspects. No scholar has offered an in-depth analysis of the paths and actions of women presidents in Latin America. As such, this book offers important contributions to the gender in politics literature.

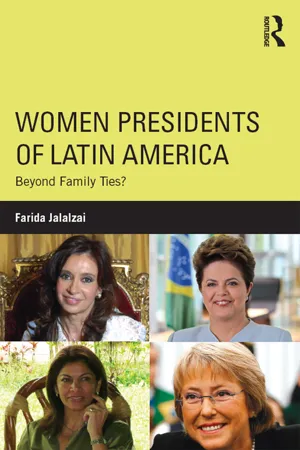

While providing valuable insight into the big picture of women in presidential politics throughout Latin America over the last several decades, this book more closely analyzes four women presidents gaining office since 2006: Michelle Bachelet (Chile, 2006–2010; 2014–), Cristina Fernández (Argentina, 2007–), Laura Chinchilla (Costa Rica, 2010–2014) and Dilma Rousseff (Brazil, 2011–). I examine these leaders in depth because they share commonalities of region and timing, arose in relatively democratic and stable settings, gained election directly by the public, and exercise significant powers. Likely in part because their presidencies are fairly new, Chinchilla and Rousseff have received little scholarly attention (but see Fernandes 2012).3 More is known about Bachelet’s first election and Fernández’s campaigns (Piscopo 2010; Franceschet and Thomas 2010; Thomas and Adams 2010; Cantrell and Bachman 2008; Tobar 2008) but not as much about their performances in office particularly in relation to impacts on women. Scholars also tend to focus on individual cases of women leaders rather than engage in comparative analysis of presidents from within the region, which is what I aim to do.

Finally, this project compares the paths and actions of women leaders to their male predecessors to verify whether women’s paths and actions are truly unique or representative of larger patterns. A common assertion, albeit a fair one, is that men also take the family path but simply might not receive as much scrutiny for these connections. To draw meaningful conclusions regarding the difference women make as presidents, their actions must also be understood within a longer history of presidential decision making. As such, I integrate relevant data on previous leaders; these actors, non-coincidentally, are disproportionately men.

My findings are primarily based on responses derived from 61 mostly in-person interviews conducted from fieldwork in Costa Rica, Brazil, Argentina, and Chile between 2011 and 2014. Respondents included political elites and experts of diverse partisan leanings such as cabinet ministers, legislators, party leaders, consultants from think tanks and academics. Respondents were provided the option of anonymity but none minded being on the record. The full list is provided in the Appendix, as well the general questions asked, and whether the interviews were conducted in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. I supplement interviews with data from media, scholarly sources, governmental and non-governmental organizations, and public opinion polls. The multi-methodological approach used is another important contribution of this work since research related to this topic tends to be derived from analyses of secondary sources rather than original data collection including in-person interviews.

Having briefly discussed the topic, the remainder of this chapter unfolds as follows. I integrate findings from larger studies on women executives to contrast general trends with potentially shifting fortunes of women leaders of Latin America. In doing so, I briefly engage with women presidents predating Bachelet. I then turn to my main questions and provide an overview of the book.

Women and Presidencies and Prime Ministerships Worldwide

As of January 2015, 98 women in 67 countries have served as national executives (presidents or prime ministers) of their countries. Fifty-seven have held the prime ministership (58 percent) while 41 have gained presidencies (42 percent). However, 19 of these women were “Acting” or “Provisional” leaders (distributed between 11 presidents and eight prime ministers). If we set these cases aside, 79 non-interim women have held these positions of power – 49 prime ministers (62 percent) and 30 presidents (38 percent). Women made sluggish progress in earlier decades. Dramatic changes occurred from the 1990s onwards. Then the number of new women leaders nearly quadrupled in the 1990s, and this pattern was repeated again in the 2000s. In fact, over three-quarters of all women presidents and prime ministers entered office in the last 20 years when women’s presence in these positions dramatically increased.

In examining conditions facilitating women’s rise to executive power, research tends to reinforce the importance of political institutions while structural variables exert mixed findings.4 Women disproportionately gain power in dual executive systems, where both a president and prime minister govern. This signifies a lower concentration of powers and women’s odds of assuming executive office increase because twice as many posts are available (Jalalzai 2008; Jalalzai 2013). Power imbalances, still the norm in dual executive systems, often relegate women to weaker positions. We may view presidents exercising authority within a unified executive system (where the president is the sole national executive) and others governing in dual executive systems with a powerful or weak prime minister as particularly strong and influential (Jalalzai 2010). Few women secure presidencies where they do not share power with a prime minister; those operating in systems where a president dominates almost always occupy the much weaker prime ministerial role (Jalalzai 2013). Women executives also disproportionately govern in parliamentary systems (Thames and Williams 2013).5

A major difference distinguishing prime ministerships and presidencies involves routes to power. Though exceptions exist, parties generally select prime ministers whereas the public typically votes for presidents. Appointments to premierships present a more auspicious opportunity for women to gain office. Even if a country evinces a socially conservative electorate, a woman may work her way up through the party ranks and ultimately become prime minister. Prime ministers gain power through appointment, lack fixed terms, and remain vulnerable to votes of no confidence or unfavorable party ballots. Moreover, prime ministerial governance depends heavily upon parliamentary collaboration rather than independent leadership. Perceptions of their negotiation and collaboration skills limit women less than their supposed inability to act unilaterally, aggressively, and decisively – all necessary presidential traits, which likely explains their relative success in attaining premierships.

Women executives also tend to hold power in multi-party systems, often governing coalitions. While their partisanships differ, they more regularly represent left-leaning parties and coalitions or, if they are symbolic presidents, may lack party affiliations altogether (Jalalzai 2010). Reserved seats and party quotas for women in legislative office also facilitate the existence of women executives (Thames and Williams 2013); quotas shape the political pipeline from which women executives may be drawn. Women’s levels in the legislature appear relevant to their eventual rise to presidencies and premierships (Jalalzai 2013; Thames and Williams 2013). Findings repeatedly fail to connect, however, the proportion of women in the cabinet to the sex of the executive (Jalalzai 2008; Jalalzai 2013; see also Krook and O’Brien 2012).6

While institutional factors profoundly affect women’s ability to gain prime ministerships and presidencies, structural conditions render mixed findings. Women executives arise in many contexts where women, on average, trail behind men in educational and professional attainment (Jalalzai 2008; Jalalzai 2013). In examining countries between 1945 and 2006, Thames and Williams (2013) found that women’s heightened labor force participation decreased the likelihood of a country being governed by a women executive (2013, 46). This does not mean that professional and educational credentials have no bearing, however, since women national leaders tend to be educated and politically experienced (Jalalzai 2013). Yet, similar to research on women legislators (Matland 1998; Moore and Shackman 1996; Yoon 2010), structural conditions do not necessarily relate to their ability to gain executive political offices. Women are more prone to rise in contexts where executives gain power through family links (Jalalzai 2013). Women also advance where a...