![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

ALL BUILDING RESULTS IN ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS. Emissions related to energy generation and manufacturing pollute the air we breathe, impact global climate and impact the health of animals and plants. Local environments are changed when land is re-shaped and vegetation is replaced with construction. The challenge of developing truly sustainable or even regenerative buildings (Cole, 2012) has led to a desire to understand building and construction from a systems-based perspective. Buildings are not static objects, but rather one component within complex environmental, social and economic systems.

Currently, “green” building practices strive to do less harm than conventional building methods. In many instances, single attributes such as percentage of recycled content or locally sourced materials, are used to identify a product as environmentally preferable. However, sophisticated users can imagine that these single attributes may not capture the total environmental picture, for example, a local product sourced in an inefficient and polluting facility might have larger environmental impact than one produced farther away in an efficient factory and shipped to a site.

Understanding a building or product from the perspective of its entire life cycle is the first step in developing sustainable and regenerative systems. How can the net impact be positive? How does one component fit into a larger system? Arguably, understanding the impacts throughout the life cycle is essential for assessing if a product or building is “green.” If we cannot determine what the impacts are, how can we be sure that we have reduced them?

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a standardized method of tracking and reporting the environmental impacts of a product or process throughout its full life cycle (ISO, 2006a: 8). Originally developed from principles of industrial ecology (Jelinski et al., 1992; Guinee et al., 2011) and first applied to the manufacturing of products within a factory (Hunt and Franklin, 1996), LCA methods and data are increasingly being used to evaluate the materials and products used in building construction and to assess a whole building from construction to end of life. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of different LCA methods and different LCA assumptions is critical for proper interpretation and use of LCA.

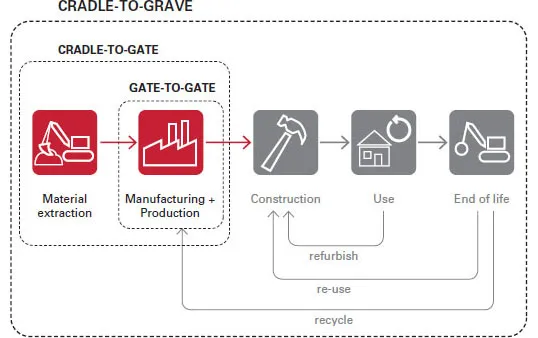

A simplified diagram of the life cycle stages of a building is shown in Figure 1.1. In order to assess the total environmental impact of a building, all life cycle phases must be considered, from material extraction, manufacturing, construction, use (operations, maintenance and refurbishment) through eventual demolition and disposal. Note that some LCA data is reported as cradle-to-gate and thus only includes impacts related to manufacturing of a product up to the “gate” of the factory. A comprehensive LCA considers impacts from cradle-to-grave. A cradle-to-cradle analysis would track how products at end of life become material resources for other products (McDonough et al., 2002).

1.1 Simplified life cycle stages of a building

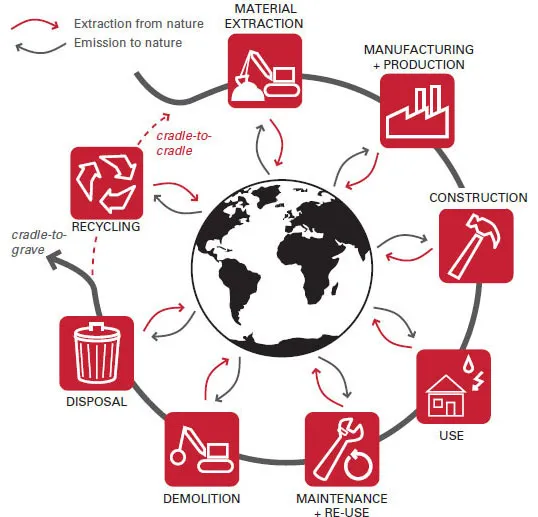

LIFE CYCLE ASSESSMENT IS NOT the same as life cycle costing, nor does it capture all environmental impacts well. Life cycle cost analysis (LCCA) tracks the financial implications of different options including first costs, operating costs and refurbishment/replacement costs. LCCA is not covered in this reference. LCA tracks the quantities of emissions to nature (e.g. kg of carbon dioxide and methane) and extractions from nature (e.g. kg of iron ore) for a studied product or process throughout its life cycle as represented in Figure 1.2.

1.2 Life cycle tracking of emissions to and extractions from nature

LCA reports impacts that can be simply and predictably measured. Thus impacts from fuel combustion and process chemical emissions are represented more effectively than local impacts such as surface water runoff or habitat disruption (see Chapter 3).

A life cycle approach to buildings requires an understanding that buildings are not static objects “finished” when construction stops and an owner occupies. Rather, buildings are dynamic changing entities that require an understanding of their impact on society and the environment throughout their life. Building operations account for a staggering proportion of the global annual energy consumption. Accordingly, increasing the energy efficiency of new and retrofit buildings has been a strong focus of the building industry. Building construction and renovation account for a sizeable minority of these energy and environmental impacts. LCA provides methods to quantify these impacts. While detailed information about methods to quantify operational energy use can be found elsewhere, LCA treats operational impacts as one life cycle stage to be evaluated.

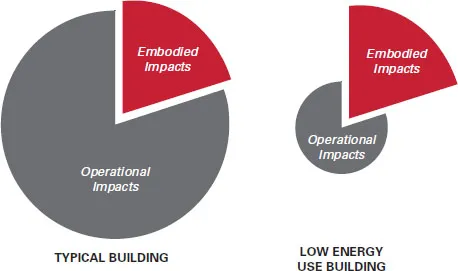

Depending on the particular building in question, the environmental impacts related to building materials, construction, maintenance and end of life (termed embodied impacts) can range between nearly 0 per cent to nearly 100 per cent. For example, a passive house with site-generated renewable operational energy would have zero operational impacts and thus the embodied impacts would be 100 per cent. The embodied impacts tent in the attic heated by coal would be near zero. There is not yet conclusive data to determine the typical ratio of impacts between construction and operation (Moore, 2013). An LCA study comparing variations on a typical theoretical building (Basbagill, 2013) demonstrate that for typical buildings, these embodied impacts account for between 10–20 per cent of the total impacts, and operational impacts account for 80–90 per cent. A recent French study that compared 70 different actual case study buildings found the embodied impacts accounted for an average of 19 per cent when assuming a 100-year life span (HQE, 2012). However, as shown in Figure 1.3, the embodied impacts become increasingly more significant as the operational efficiency improves.

1.3 Relative impact of a building’s embodied vs. operational impacts

LCA can provide the analytical framework to identify environmental impacts, improve manufacturing processes and compare between alternatives. LCA provides quantifiable metrics by which to assess the environmental impacts of a product or process, helping to avoid generalized statements and ideally can help avoid “green-washing”.

1.1 LCA: environmental accounting

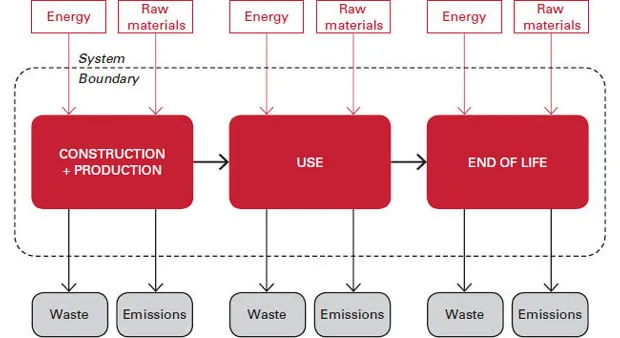

LCA IS A METHOD OF ENVIRONMENTAL ACCOUNTING: tracking the inputs from nature (such as limestone, water and coal) and outputs to nature (such as waste, carbon dioxide and methane) considering all of the processes that take place during the manufacture, use and disposal of a product (or system). Figure 1.4 represents how each stage of a building requires energy and material inputs and outputs wastes and emissions. LCA tracks these inputs and outputs. As an accountant can use the “cash” or “accrual” method to track a company’s economic performance and attain different results, there are different methods that can be used when performing an LCA.

1.4 LCA tracks inputs from nature and outputs to nature that cross the “system boundary”

A life cycle inventory (LCI) is a detailed accounting of the quantities of raw materials used, the products produced, the waste outputs and the emissions to air, land and water. See Chapters 2 and 4 for more details on the generation of LCI data. In more complex p...