eBook - ePub

Handbook of Reading Assessment

A One-Stop Resource for Prospective and Practicing Educators

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of Reading Assessment

A One-Stop Resource for Prospective and Practicing Educators

About this book

The Handbook of Reading Assessment, Second Edition, covers the wide range of reading assessments educators must be able to use and understand to effectively assess and instruct their students. Comprehensive and filled with numerous authentic examples, the text addresses informal classroom based assessment, progress monitoring, individual norm-referenced assessment, and group norm-referenced or 'high-stakes' testing. Coverage includes assessment content relevant for English language learners and adults. A set of test guidelines to use when selecting or evaluating an assessment tool is provided.

New and updated in the Second Edition

- Impact on reading assessment of Common Core Standards for literacy; increased top-down focus on accountability and high stakes tests; innovations in computerized assessment of reading

- Latest developments in Response to Intervention (RTI) model, particularly as they impact reading assessment

- International Reading Association standards for reading educators and brief discussion of International Dyslexia Association standards

- Types of reading assessment, including discussion of formative versus summative assessment

- Expanded coverage of assessment of reading motivation

- Expanded coverage of writing assessment

- New and revised assessments across genres of reading assessment

- Companion Website: numerous resources relevant to reading and writing assessment; suggestions for evidence-based instructional practices that can be linked to assessment results; PowerPoint slides; test bank; study guides; application exercises

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handbook of Reading Assessment by Sherry Mee Bell,R. Steve McCallum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

one

Assessment of Reading

The Context

Advance Organizers: In This Chapter We Describe

- Context for reading assessment

- Role of reading assessment in instruction

- Purposes of reading assessment

- Definition of reading

- Evidence-based practices in reading

- Major types of reading assessments

- Standards for teaching reading

Educators in Action

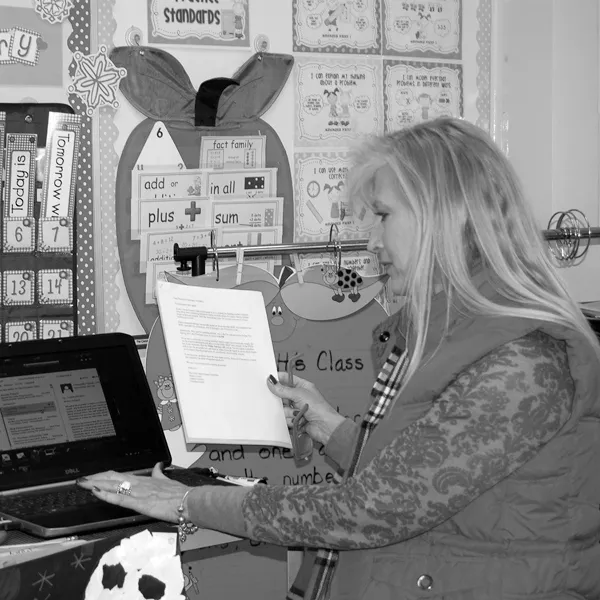

We begin this book by introducing four teachers, a reading specialist, a school psychologist, and an administrator. If you are an educator or an educator-to-be you will identify with one or more of these individuals because they work in real settings and experience real challenges, perhaps like those you have experienced or soon will face. Throughout the book you will learn about some of the students of these four teachers, and how the teachers and related school personnel use information from assessment to improve their instruction.

Meet Lesa Crockett

Lesa Crockett is a first-grade teacher with 17 years’ experience in a city school in a large district with a diverse population of students, primarily White (72%), but also Black (18%), Hispanic (5%), and Asian (5%), with socioeconomic status (SES) ranging from below poverty level to affluent (32% are eligible for free or reduced price lunch). Increasingly, she has at least one student per year in her class for whom English is a second language; the ELL population in her school is 6% and 12% are students with disabilities. To teach reading, Lesa uses the basal series required by her school district. She supplements with leveled readers to ensure students get plenty of practice with books they can read and with specific phonics activities that teach students to recognize patterns of letters and the sounds they typically make. Lesa thinks that teaching her students to read is the most important part of her job. And she is usually pretty successful. That is, most of her students leave her classroom reading short books or stories of connected text, can read orally between 25 and 75 words per minute, and, importantly, most seem to like reading. However, she also considers teaching reading to be her biggest challenge. Like most other teachers, she feels pressure to be accountable for performance of all her students, including those who enter first grade not knowing the alphabet and those from homes in which English is not spoken or read. Lesa routinely administers unit tests associated with the district-adopted basal series that measure progress on a variety of reading skills. However, she is concerned that she doesn’t have the time to plan instruction based on these assessments. And, recently her district has begun routine assessment of all students, a process called universal screening. She is concerned that she will not have the time or skills to implement another assessment process in her class.

Meet Greg Haywood

Greg Haywood is a special education teacher in a rural K-6 school. Like Lesa, he believes his biggest challenge is to teach literacy skills. The school serves almost 600 children in a rural socioeconomically depressed area with 70% receiving free or reduced price lunch; 98% are White and 2% are Hispanic; 12% are eligible for special education services. His school participates in a literacy project with a university in the area. The classroom teachers have implemented a core program that rests heavily on guided reading, use of leveled readers, and time to work on word skills and writing. His school also participates in a federal initiative to boost reading skills at the lower grades, and has recently begun implementing the response to intervention (RtI) model associated with federal special education laws. Greg is concerned that the classroom teachers in his building are overwhelmed by seemingly contradictory approaches associated with the different initiatives and that reading and special education staff need to have better communication. Also, he is concerned that teachers and students have to spend so much time on assessment activities that teachers may not understand and, consequently, that may not be used to plan instruction.

Meet Harley Charles

Dr. Harley Charles is a tenth-grade biology teacher in the same large district as Ms. Crockett. He has 24 students in his class, but finds it very difficult to hold the attention of all of them. In fact, almost a third of the students sit near the back of the class and require intermittent prodding to keep them attentive. They whisper among themselves, yawn, stare off into space, and generally remain off task. Four or five of the strongest academic students sit over near the window, doodle, stare outside, or read paperbacks they hide inside their huge biology textbooks. They do well on tests, and are quiet during class lectures, but are obviously bored much of the time. These students are typically able to answer questions when called on, and on those occasions when Dr. Charles feels he can afford to take the time to engage the class in a discussion, they become motivated and energized. The rest of the class is pretty well behaved and generally attentive, but Dr. Charles is frustrated because of the variable behavior of the students and the wide range of performance. He wonders if it is possible to engage the whole class, and how he could obtain the information to help him plan instruction better. He suspects that the most poorly behaved students cannot comprehend the content in the textbook, even though they are required by state law to pass his course and an end-of-course test in order to graduate.

Meet Maria Sanchez

Maria Sanchez is an adult educator employed in an adult education center housed in the district in which Ms. Crockett and Dr. Charles teach; she teaches older adolescents and young adults who left high school before graduating. Like Lesa and Greg, Maria believes her most important task is to teach literacy. Her students exhibit a wide range of reading levels; a few are beginning readers, many are reading between third- and fifth-grade level, and a few are reading at higher levels. Maria usually has very limited information about her students upon entry into her class, typically just a single measure of reading comprehension from a group administered achievement test for adults. She wants to learn more about assessment so that she can group for instruction, plan appropriate experiences for the diverse learners in her class, and more specifically document their progress over time.

Meet Ms. Swafford

Ms. Kristen Swafford is a reading specialist serving Mr. Haywood’s school. Motivated to become a more effective teacher for her third-grade students, she took advanced coursework in instruction and assessment of reading at a nearby university and earned a reading specialist credential while on the job. Recognized by her principal for her ability to differentiate instruction and improve achievement of her most at-risk students, she was designated a literacy coach and currently consults with teachers in her school, models lessons, conducts and help interpret assessments, and provides leadership in instructional planning. She also performs informal observations and provides feedback to novice teachers and those in need of support.

Meet Mr. Oakley

Mr. Richard Oakley is a school psychologist by training and experience; he serves a high school and the middle and elementary (Ms. Crockett’s school) that feed into it. As a school psychologist, Mr. Oakley is an assessment expert, and is responsible for providing a variety of services to his system, including coordinating the choice of assessment instruments used. Mr. Oakley is committed to direct service to students, and accepts referrals from teachers and parents. In his role as a school psychologist he may administer various tests to students who are referred because they are at risk for academic or behavioral problems. In that role he often sees students who have reading difficulties. His system is like most others in the U.S. in that the majority of students who are referred for academic problems exhibit reading difficulties (Lyon, 1996; President’s Commission on Excellence in Special Education, 2002). Like other school psychologists Mr. Oakley serves as a member of a school-based team and consults with teachers and parents early in the referral process. Ultimately he helps determine specific academic (and perhaps cognitive) performance levels, reasonable reading goals, and optimal instructional interventions. Mr. Oakley’s system employs an RtI model and as an assessment expert he advised system administrators as to the particular instruments used to screen and monitor the progress of all students who exhibit at-risk reading and math skills. Students who are identified as at risk based on routine progress monitoring within the RtI model are then referred for additional in-depth assessment.

Meet Ms. McCall

Ms. Charlotte McCall is a former fifth-grade teacher and is currently a principal of a mid-size K-6 school (Mr. Haywood’s school) and in that role she is responsible for providing leadership and supervision of teachers and others who work in the school. Ms. McCall is the primary contact person in the school for upper-level administrators and the superintendent. Ms. McCall helps select the curriculum used by teachers in the school, is the leader of the school-based team that makes decisions about at-risk students, evaluates the performance of teachers, and is ultimately responsible for academic outcomes produced by teachers and others who serve students directly. At various points in the book we observe her contributions to ensure acceptable reading outcomes (e.g., input regarding selection of appropriate reading assessment instruments, use of the data produced by these instruments, supervision of the linkages between assessment and instruction, and the communication of outcomes to system administrators and parents). Throughout this book we refer to the work of Ms. Swafford, Ms. McCall, and Mr. Oakley and we revisit the classrooms of Ms. Crockett, Mr. Haywood, Dr. Charles, and Ms. Sanchez as we discuss assessment strategies these teachers can use to help their students.

What Is the Role of Assessment in Instruction?

It is hard for some teachers to see the connection between their teaching and assessment, particularly between daily classroom instruction and large scale end-of-year assessment. But effective teachers appreciate the importance of assessment. They use assessment information to plan and implement instruction based on knowledge of what their students know and do not know, as well as what they can and cannot do. Assessment can be as informal as listening to students express themselves in class or in the hallway or as formal as administration of a standardized achievement test such as the National Assessment of Educational Progress or NAEP (www.nces.ed.gov/naep).

Unfortunately, the relation between assessment and instruction is only one of hundreds of things new teachers have to learn. Consequently, sometimes both new and inservice teachers have a vague understanding or even misconceptions about the role of assessment in planning instruction. For example, many educators tend to think of assessment and testing as interchangeable terms, though experts (e.g., Overton, 2012) distinguish between the two. According to Overton, assessment “includes many formal and informal methods of evaluating student progress and behavior” (p. 3), while testing is “a method of evaluating progress and determining student outcomes and individual student needs” (p. 3). Thus, assessment defines a broader range of activities, and includes testing as one technique to gather information. Overton’s definition implies that assessment includes decision making regarding students’ strengths and needs and the match between those strengths/needs and instruction, though some refer to the decision making itself as a separate process and refer to this component as “evaluation.” The evaluation process is informed by routine and targeted testing, sometimes by the teacher, sometimes by other professionals like Ms. Swafford, the reading specialist, or Mr. Oakley, the school psychologist. All this information is shared with administrators, like Ms. McCall, and with parents, often in a school team setting.

Teachers like Ms. Crockett, Mr. Haywood, Dr. Charles, and Ms. Sanchez can be most effective when they use assessment information routinely. For example, the kindergarten teachers in Ms. Crockett’s school use checklists throughout the year to assess their students’ knowledge of the alphabet. Primary-level teachers may administer unit tests that accompany basal readers to ensure students’ mastery of word analysis and comprehension skills. Intermediate and secondary school teachers, like Dr. Charles, may use teacher-made worksheets and quizzes that are tied to units of study to gauge student mastery of instructional objectives; in addition, they can use curriculum-based measurement and standardized test results to help them understand how their students vary on fundamental skills such as reading fluency.

Consider the dilemma Dr. Charles faces in his class, as described in the opening scenario. Obviously several of his students are not motivated. This situation is not unusual. In fact, Hargis (2006) described a very similar situation in an article in the Phi Delta Kappan—of 24 students in a tenth-grade biology class he observed, nine students were reading at or below the eighth-grade level, seven were reading in the ninth- to tenth-grade range, and eight were at the eleventh-grade level or higher, but all were expected to read a textbook written at the 10.2 readability level! According to national data Hargis presented, this level of variability is common, even to be expected in schools, but this variability leads to many of the behavior challenges teachers face. Consequently, he made a case for using instructional materials of appropriate difficulty level, rather than expecting all students to work at a pace that is appropriate for middle ability students.

Teachers like Ms. Crockett and Mr. Haywood and reading specialists like Ms. Swafford sometimes use informal reading inventories to identify appropriate levels of instruction for their students, and can target specific skill gaps for individuals. Effective educators use information from these assessments to plan further instruction, reteaching if necessary, to ensure mastery. These informal measures can be used in conjunction with information from many other types of assessment, including norm-referenced group achievement tests (typically given near the end of the school year to ensure progress of individual students, classes, schools, or systems) and individualized norm-referenced achievement tests, usually administered by a school psychologist like Mr. Oakley to determine eligibility for special education. At the mos...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: Assessment of Reading: The Context

- Chapter 2: Nature of Reading

- Chapter 3: Assessing Motivation to Read

- Chapter 4: Informal Assessment: Informing Instruction

- Chapter 5: Informal Assessment: Progress Monitoring

- Chapter 6: Formal Assessment of Reading: Individualized Assessment

- Chapter 7: Formal Group Assessment: Focus on Accountability

- Chapter 8: Using Informal and Formal Assessment Data to Inform Teaching

- Appendices

- Glossary

- Index