![]()

1. History

This chapter will outline the general nature of translation history, particularly its parts, its background, and a few reasons for its existence. These are all fundamental aspects of the approach to be elaborated in greater detail in the following chapters.

History within translation studies

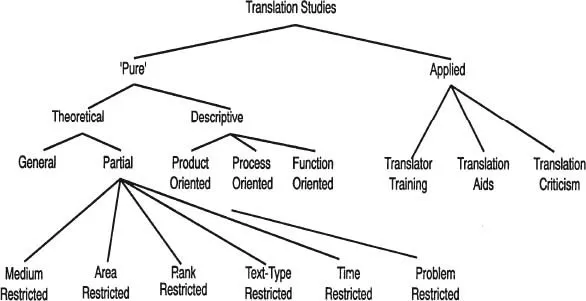

James S Holmes’ seminal lecture ‘The Name and Nature of Translation Studies’ (1972) set out to orient the scholarly study of translation. It put forward a conceptual scheme that identified and interrelated many of the things that can be done in translation studies, envisaging an entire future discipline and effectively stimulating work aimed at establishing that discipline. Historically, this was a major step forward, none the least because it involved a frontal attack on the hazy but self-assured categories that had long been used to judge translations. Holmes’ categories were simple, scientifically framed, and hierarchically arranged: ‘Applied’ was opposed to ‘Pure’, the latter was broken down into ‘Theoretical’ and ‘Descriptive’, then ‘Descriptive’ divided in turn into ‘Product Oriented’, ‘Process Oriented’ and ‘Function Oriented’, and so on. Figure 1 shows the apocryphal graphic form these categories received later from scholars who saw it as a legitimate point of departure. Many wonderful things found a place in this map; a few more have benefited from the modifications and variants proposed since (notably Lambert 1991a, Snell-Hornby 1991, Toury 1991). Of course, translation studies cannot be reduced to this one map, and the map itself has been evolving dynamically, along with the lands it purports to represent. Yet the curious fact remains that neither Holmes nor his commentators – at least those subscribing to the map and its variants – explicitly named a unified area for the historical study of translation. This merits some thought.

It could be that everything Holmes called ‘descriptive’ is automatically historical. But is this a fair reading of what we have on the map? Holmes certainly allowed that the translations of the past could be studied under his ‘product-oriented descriptive’ branch, and there is no reason why the historical functions of translations might not also be studied under ‘function-oriented description’. Yet here we run into a series of problems. Does the Holmes map mean history is just a matter of describing objects? Is there no history in apparently non-descriptive slots like ‘Translation Criticism’? Do ‘Theoretical Studies’ somehow stand outside of history? And why does Holmes’ theoretical branch only explicitly include history as a possibility for ‘time-restricted theories’ (specifically the subset dealing with ‘the translation of texts from an older period’) as well as its obvious role in a general ‘history of translation studies’ (1972:72, 76, 79)? Whatever the reasons behind these categories, the field of history is strangely fragmented on both sides of the descriptive/theoretical divide.

Figure 1

Holmes’ conception of translation studies (from Toury 1991:181)

A facile way to overcome this fragmentation is to claim that all the categories are interrelated dialectically. You are supposed to add or imagine little arrows all over the place. Is this a real solution? If arrows really do go from all points to all other points, who would need the map in the first place? Maps name consecrated plots and the easiest routes between them. The Holmes map suggests translation history has no consecrated plot within translation studies. Translation historians of any but the narrowest variety would seem condemned to jump from one patch to another, describing products here, analyzing functions there, and finding themselves marginally implicated in a metadescription of the whole lot. The Holmes map also omits a few areas of possible interest: it delineates no ground for any specific theory of translation history, nor for historiography as a way of applying and testing theories (although this is certainly what Holmes wanted us to do). Despite its many virtues in its day, I suggest the map is no longer a wholly reliable guide.

I sow these few doubts because some scholars, notably Gideon Toury (1995:10), see the Holmes map as mandatory orientation for any work in translation history, and indeed for translation studies as a whole. Whatever we do now, it seems, should be located somewhere within the schemata inherited from the past. To do otherwise, claims Toury, would be to risk compromising the “controlled evolution” of translation studies. Yet is there any reason to suppose that the Holmes map is automatically suited to what we want to do in translation studies now? Does the map infallibly locate places for the particular hypotheses we want to test or the specific problems we are trying to solve? If not, what kind of price are we being asked to pay for the ‘controlled evolution’ of a scholarly discipline? Exactly who is doing the controlling, and to what end? Indeed, aren’t the problems to be solved of more importance than the maintenance of an academic discipline? No matter how pretty the maps, if a branch of scholarship fails to address socially important issues, it may deserve to disappear or to be relegated to academic museums, like the first navigation charts of Terra Australis.

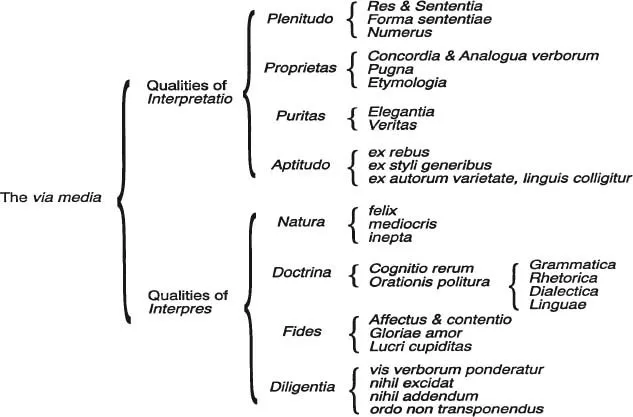

Maps are peculiar instruments of power. They tend to make you look in certain directions; they make you overlook other directions. Consider, for instance, the general orientation of the Holmes map in its consecrated graphic form (Figure 1). Look at the form, not the labels. Now compare that modern map with Figure 2, which is Lawrence Humphrey’s much earlier attempt to envisage a global translation studies (first published in 1559). I suggest there are two main differences.

Figure 2

Diagramma from Lawrence Humphrey’s Interpretatio linguarum (Basle 1559) (from Norton 1984:12)

First, Humphrey’s map breaks down the categories horizontally, from left to right, whereas the Holmes map is vertical, going from top to bottom, like company organization charts. Thanks to the modern verticality, the most general theoretical categories find a presidential space well away from empirical details. Ungenerous minds might suspect the modern maps represent a kind of professorial power, allocating the top to an all-seeing eye able to place the more specific subjects ranged along the bottom. Yet this would be unfair: translation studies is still far too small for such a radical division of labour; a good deal of the spadework at the bottom is actually being done by the same names that are looking out from the top. But if everyone can be everywhere, what real good is the map?

Second, the major division in the sixteenth-century map is between translation (interpretatio) and the translator (interpres), the process-product and the agent, whereas the modern map calmly divides up the products – translations – without offering so much as a glance at any translator, living or dead. Where did all the people go? If the modern maps provide images of organizational domination, then the people most effectively dominated must surely be researchers and translators, especially the ones with flesh, blood, mobility and subjectivity. These people seem to have been excluded from the world of ‘pure research’. Perhaps they deserve to be put back in.

One of my aims in this book is to bring together a few of these fragmented or overlooked aspects of maps. I would like to see translation history as a unified area for the humanistic study of human translators and their social actions, both within and beyond their material translations. Of course, in the process of presenting my arguments, I will be drawing many maps of my own. Maps are instruments of power. They name and control. A displacement of power in this field might thus be intimated by a certain remapping.

The parts of translation history

There is nothing particularly new or revolutionary in wanting to write about the history of translation. Yet tradition provides a rather indefinite vocabulary for the undertaking. As the Holmes map suggests, there are some doubts as to how the historical object should be named, what the general field is called, and what kinds of subdivisions are to be allowed for. Not all these doubts can be dispelled here. A few internal conventions might nevertheless be proposed, if only to describe the words I’ll be using.1

Translation history (‘historiography’ is a less pretty term for the same thing) is a set of discourses predicating the changes that have occurred or have actively been prevented in the field of translation. Its field includes actions and agents leading to translations (or non-translations), the effects of translations (or non-translations), theories about translation, and a long etcetera of causally related phenomena.

Thus conventionalized, translation history can be subdivided into at least three areas: ‘archaeology’, ‘criticism’ and something that, for want of a better word, I shall call ‘explanation’:

• Translation archaeology is a set of discourses concerned with answering all or part of the complex question ‘who translated what, how, where, when, for whom and with what effect?’. It can include anything from the compiling of catalogues to the carrying out of biographical research on translators. The term ‘archaeology’ is not meant to be pejorative here, nor does it imply any particularly Foucauldian revelations. It simply denotes a fascinating field that often involves complex detective work, great self-sacrifice and very real service to other areas of translation history.

• Historical criticism would be the set of discourses that assess the way translations help or hinder progress. This is an unfashionable and perilous exercise, not least because we would first have to say what progress looks like. In traditional terms historical criticism might broadly cover the philological part of historiography, if and when philology conjugates notions of progress as moral value (and the best of it used to). Yet the resulting criticism cannot apply contemporary values directly to past translations. Rather than decide whether a translation is progressive for us here and now, properly historical criticism must determine the value of a past translator’s work in relation to the effects achieved in the past. This would be the difference between historical and non-historical criticism. Perhaps happily, neither historical nor non-historical criticism will be of great concern to us in this book, since they both require degrees of ideological certitude for which I await revelation. A few of the following pages (35-36, 168-169) will nevertheless suggest, for example, that a certain French translator of Nietzsche could have contributed to highly non-progressive cultural conflict. Those pages, tenuous and tentative as they are, should count as historical criticism, or at least as a bookmark for where criticism is required. Clearly, I would welcome rather than shun any critical minds brave enough to say where we should be going and how translations can help get us there. Their activity should also be part of our endeavour. In the meantime, our translation history has many very practical questions to answer before progressive moral values can be distributed with any degree of confidence.

• Explanation is the part of translation history that tries to say why archaeological artefacts occurred when and where they did, and how they were related to change. Archaeology and historical criticism are mostly concerned with individual facts and texts. Explanation must be concerned with the causation of such data, particularly the causation that passes through power relationships; this is the field where translators can be discovered as effective social actors. Other levels of explanation, perhaps dealing with technological change or power relations between social groups, can equally privilege large-scale hypotheses concerning whole periods or networks. ‘Why?’ might seem a very small question for a project that should properly encompass all the other parts of translation history. Yet it is by far the most important question. It is the only one that properly addresses processes of change; it is the only one seriously absent from the Holmes map. A history that ignored causation would perhaps be able to describe actions and effects, it might even have a one-dimensional idea of progress, but it would not recognize the properly human dimension of documents and actions as processes of change.

The interdependence and separateness of the parts

All translation history comprises or assumes discourses from all the above categories. The discourses are not really ‘parts’ in the sense that they can be detached from the whole. They might be thought of as parts that individuals or individual groups can sing in order to make up full harmonies as they go along. The parts can be sung by themselves. There can even be a few star soloists. Yet each individual part assumes a relation to the wider whole. It is impossible to write an archaeological catalogue or even locate items for catalogues unless one has some general idea of the change process framing those values (explanation), and there is little reason to do this unless one at least hopes the past can lead to a positive future (criticism). Similarly, there can be no criticism or explanation without archaeological evidence, and no explanation of change without some idea of the values involved in change. In short, none of these three parts can assume epistemological independence from the others. Anyone doing translation history is to some extent involved in all three activities (there is no purely ‘informative’ or ‘descriptive’ discourse, just as there is no abstract speculation without at least some archaeological grounding). However, since the superficial modes of presentation are quite different, there are good practical reasons why each individual part should be considered in relative isolation.

Why maintain the above distinctions? First, they are a way of organizing a book on the subject. The following chapters will go from archaeology to questions of causation, with just a few passing comments on criticism. This structure is useful to the extent that any signpost is better than none, and a communicative virtue is a very serious virtue. Although unwritten research can and should wander from one set of questions to another, doing history is also a matter of communicating the results of research. This is important because archaeology, criticism and explanation tend to mix quite badly on the more practical levels of translation history. Each discourse has its optimal mode of presentation. Archaeology is suited to lists; criticism is suited to analysis and argument; explanation is often best when close to good storytelling. If archaeological lists weigh down explanatory storytelling, the result is immediate boredom, just as apparent flippancy could result from good storytelling in the midst of archaeology or detailed evaluation. Keeping the parts relatively separate could be a way of keeping them relatively interesting.

A brief example might illustrate the point. Valentín García Yebra’s potted history of translation in Spain (1983) is both explanatory and critical with respect to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, where a reasonable amount of archaeological work had been done before him. But since little archaeology had been done for the following centuries, García Yebra’s translation history quickly becomes a list of dates and texts, written in prose but reducing narrativity to repeated claims that the whole catalogue would take up far more than the available space (‘to list all the great translations of this period would require several books…’, and so on). The result is not particularly fruitful, since a straight list would have been more readable. Yet the problem doesn’t stop there. A university textbook based on García Yebra (Pascua and Peñate 1991:2-4) gives a basically narrative summary of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (mixed together as the ‘School of Toledo’) then crashes into a wonderfully reductive sentence: “After the seventeenth century, translations went parallel with literature” (1991:4). This sentence reflects a certain understanding of García Yebra’s lists for the period in question, but it is not helpful history: it shows nothing and it explains nothing; it is neither archaeological nor explanatory. The initial solution should have been for García Yebra to keep the lists and the stories in separate paddocks. Lists are for archaeology; century-spanning prose belongs to explanatory discourse.

The division of translation history into separate but related parts could also prove useful for the actual organization of research. Although history requires the three parts, no one is obliged to engage in all of them in an equal way or at the same time. It is impossible to insist that everyone should have read everything, and mostly unprofitable to ask exacting archaeologists to defend a philosophical position in the history of ideas. Balanced and vital history should instead come from the constitution of research teams able to integrate expertise from the various disciplines bearing on a particular field, not just from the philological perspective but also paying attention to insights from social and economic history. The divisions could become guidelines for exchange, collaboration and teamwork.

Examples of the need for teamwork are not difficult to find in studies of Iberian translation history. Explanatory historians have traditionally rushed ahead of everyone and everything, advancing global hypotheses and not infrequently making mistakes. The archaeologists often come up behind, building castles stone by stone and mistrusting large-scale conceptual conclusions. A classic case is the French historian Amable Jourdain, who claimed to have discovered the Toledan ‘college of translators’ as a result of very hard work: “We confess, with a joy that all men of letters will appreciate, that the discovery of this college of translators has made up for the innumerable thorns that have covered our path” (1873:108). What was he so proud of? Jourdain had actually found two manuscripts in which different translations seemed to name a certain Raimundus, archbishop of Toledo, as their patron. The historian had struggled to locate these manuscripts, so he thought a discovery would be just compensation. Monsieur Jourdain found what he wanted to find, and was no doubt doubly pleased because Archbishop Raimundus of Toledo, the patron, just happened to be every bit as French as Jourdain himself. However, work by Marie-Thérèse d’Alverny (1964), a French translation archaeologist who deserves real praise, compared 45 manuscripts from right across Europe and discovered that one of the two texts where the archbishop was named actually had quite a different meaning: Jourdain had read a comma that had little reason to be there and he had been misled by a proper name (‘Johannes’ instead of ‘Johanni’). The wider manuscript tradition made it clear that the sponsor of one of the translations was not Archbishop Raimundus but his successor Johannes. The careful archaeology of a syntactically implied comma thus pulled down an entire explanatory edifice. The French archbishop became the patron of just one translation, with no firm connection with anything like a college or school of translators. Archaeology undid hasty explanation. Yet both approaches were surely necessary. If Jourdain had not formulated his large-scale concept, d’Alverny’s alternative comma would not have been important as an object of research. The comma may well have been lost among many t...