eBook - ePub

Improving Teaching through Observation and Feedback

Beyond State and Federal Mandates

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Improving Teaching through Observation and Feedback

Beyond State and Federal Mandates

About this book

In response to Race to the Top, schools nationwide are rapidly overhauling their teacher evaluation processes. Often forced to develop and implement these programs without adequate extra-institutional support or relevant experience, already-taxed administrators need accessible and practical resources. Improving Teaching through Observation and Feedback brings cutting-edge research and years of practical experience directly to those who need them. In five concise chapters, Thomas Good and Alyson Lavigne briefly outline the history of RttT and then move quickly and authoritatively to a discussion of best practices. This book is a perfect resource for administrators reworking their processes for new evaluation guidelines.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Improving Teaching through Observation and Feedback by Alyson L. Lavigne,Thomas L Good in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Éducation & Éducation générale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Being a Principal in an Era of High-Stakes Teacher Evaluation

We will illustrate (and most of our readers know) principals work long hours and have difficult jobs. Yet policy makers now call for principals to spend more time supervising teachers. This advocacy is done without any advice about how principals can find time to do this or any evidence that increasing the amount of time principals spend in classrooms will increase student achievement. Principals today are under increased pressure to improve their schools, and advice about how they should do this abounds.

With this context in mind, this chapter describes certain characteristics of today’s school principal. We look at factors such as salary, years of experience, and other demographic variables. Some information is presented as an average across the U.S. Some information is reported at the state level to show that context is often important and that there is considerable variation in principals’ beliefs and job situations.

Next, we report on principals’ beliefs about their job. Although conceptions of the “good” principal continue to evolve, consensus is that the job is very demanding. It is useful to consider issues where principals believe they have more or less influence and to consider the levels of job satisfaction and stress that principals experience. Then, we turn to a description of what principals are expected to do based on considerations from theory, professional societies, and those who study school leadership. We describe the many roles that principals are expected to and do play. Lee Sherman (2000) provides the perfect advance organizer:

Research tells us that principals are the linchpins in the enormously complex workings, both physical and human, of a school. The job calls for a staggering range of roles: psychologist, teacher, facilities manager, philosopher, police officer, diplomat, social worker, mentor, PR director, coach, cheerleader. The principalship is both lowly and lofty. In one morning, you might deal with a broken window and a broken home. A bruised knee and a bruised ego. A rusty pipe and a rusty teacher.

(p. 2)

After describing the roles noted by Sherman, we illustrate that expectations for what good principals “should do” are varied and complex, and often change without any evidence to suggest that the recommended changes will work. Thus, it is not surprising that the research base on effective principals is undeveloped as definitions of what constitutes good practice vary over time.

We examine principals’ tasks and see that they respond to an overwhelming set of duties replete with frequent interruptions. Sometimes they must do two or more things simultaneously. Principals face many demands, but they have limited time available to complete duties. We explore how principals use their time, and we summarize the results across several studies. One major finding is that principals generally do not spend much time observing/evaluating teachers. And, despite policy makers’ (and state and federal mandates’) push for principals to spend more time supervising teachers, those who have studied and who have reported this finding have not recommended that principals necessarily spend more time on this activity.

We end this chapter considering modern-day issues that characterize the work and lives of school leaders. We revisit what is known about what principals do and within the context of new reform demands. The fact that principals spend little time on supervision and evaluation creates tension with the state and federal mandates that call for increased time spent on these tasks. We ask: Where would principals find the time to do this? Do they have this knowledge? We address these questions in Chapter 2.

The Face and Voice of School Principals

Table 1.1 shows (based upon data from the U.S. Department of Education 2011–2012) how principals vary in terms of gender, race/ethnicity, highest degree earned, average age, experience, annual salary, and average hours spent on the job per week. For example, 51.6% of principals are female. The average number of years of experience of principals is 7.2; the average salary for principals for fewer than 3 years is $83,500, and for those with 10 or more years of experience, $96,000. The average age of principals is 48, and the average hours spent per week on all school-related activities is 58.1.

Table 1.1 also reports these same data during 2007–2008. We see that principal characteristics are fairly stable during this time period. For example, the percentage of teachers who are female, male, and white remains essentially the same. One exception is that principal salaries at all levels increased notably (given the economy) from 2007 to 2012. And this is especially true for principals with 10 or more years of experience (whose salary rose by $14,000). We have presented averages for principals across the U.S., but describing principals is much more complicated than averages suggest. For example, Table 1.2 illustrates the variability in principal salary in five randomly chosen states.

Principal Characteristics | 2011–2012 | 2007–2008 |

|---|---|---|

Gender | ||

Female | 51.6 | 51.0 |

Male | 48.4 | 49.0 |

Race/ethnicity | ||

White | 80.3 | 80.9 |

Black | 10.1 | 10.6 |

Hispanic | 6.8 | 6.5 |

Other | 2.8 | 2.0 |

Highest degree earned | ||

Bachelor’s degree or less | 2.2 | 1.5 |

Master’s degree | 61.7 | 61.1 |

Education specialist or professional diploma | 26.2 | 29.0 |

Doctorate or professional degree | 9.9 | 8.4 |

Average age | 48 | 49 |

Experience | ||

Average years of total experience | 7.2 | 8.1 |

Average years at current school | 4.2 | 4.8 |

Average annual salary, by years of experience | ||

Fewer than 3 years | $83,500 | $73,500 |

3–9 years | $90,900 | $80,200 |

10+ years | $96,000 | $82,700 |

Average days in contract year | 230 | 227 |

Percent of principals newly hired | 8.6 | 9.3 |

Average hours spent per week on | ||

All school-related activities | 58.1 | 58.4 |

Interacting with students | 22.5 | 20.8 |

Percentage of principals who thought they had a major influence on: | ||

Evaluating teachers at their school | 96.2 | 94.2 |

Hiring new full-time teachers at their school | 85.1 | 90.4 |

Compensation for principals in Pennsylvania is considerably higher, at all levels of experience, than in Montana. The level of absolute compensation for principals needs to be studied in relation to the fact that the principal contract year is roughly 230 days. Principals’ salaries also need to be considered in terms of principals’ job satisfaction, the extent to which they can control work conditions, and the amount of stress they experience. Not only do principals’ salaries vary, but also their beliefs about the extent to which they can influence their job conditions vary (see Table 1.3).

State | Average annual salary | Less than 3 years | 3 to 9 years | 10 years or more |

|---|---|---|---|---|

United States | 90,500 | 83,500 | 90,900 | 96,000 |

Louisiana | 74,800 | 71,300 | 74,200 | 79,600 |

Montana | 65,800 | 53,200 | 68,900 | 75,700 |

Pennsylvania | 98,100 | 92,100 | 96,600 | 105,500 |

Utah | 82,100 | 72,700 | 83,900 | 84,500 |

Wyoming | 92,500 | 80,700 | 90,100 | 99,900 |

Source: U.S. Department of Education (2013).

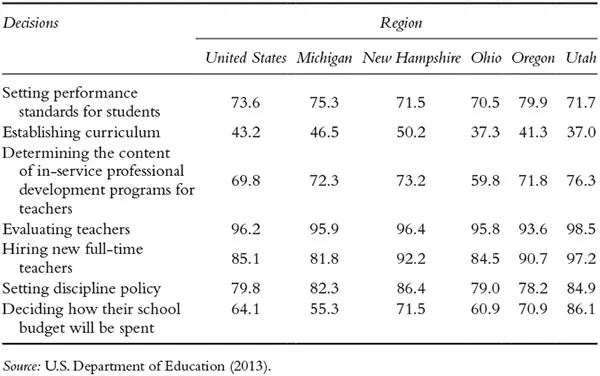

TABLE 1.3 Percentage of Public School Principals in Five Randomly Selected States Who Thought They Had a Major Influence on Decisions Concerning Various Activities at Their School

The context in which the principal operates is important. Although virtually all principals believe they have a dominant voice in evaluating teachers, principals clearly believe that they have considerably less influence on the curriculum. This is the case in all selected states but especially so in Ohio and Utah. The fact that principals are accountable for student achievement growth—yet have little control over curriculum—must be frustrating to some. Readers interested in states other than those reported can consult the National Center for Education Statistics, Schools and Staffing Survey website (https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/sass/).

School Principals: Role Conceptualizations and Expectations

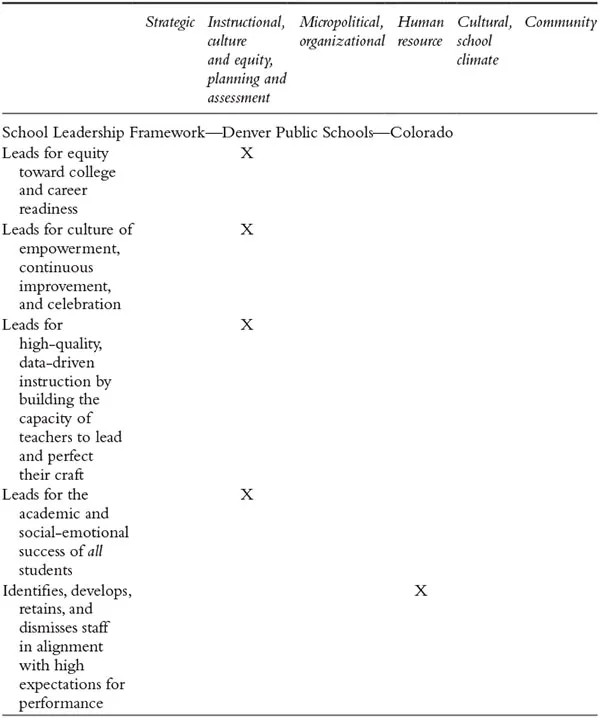

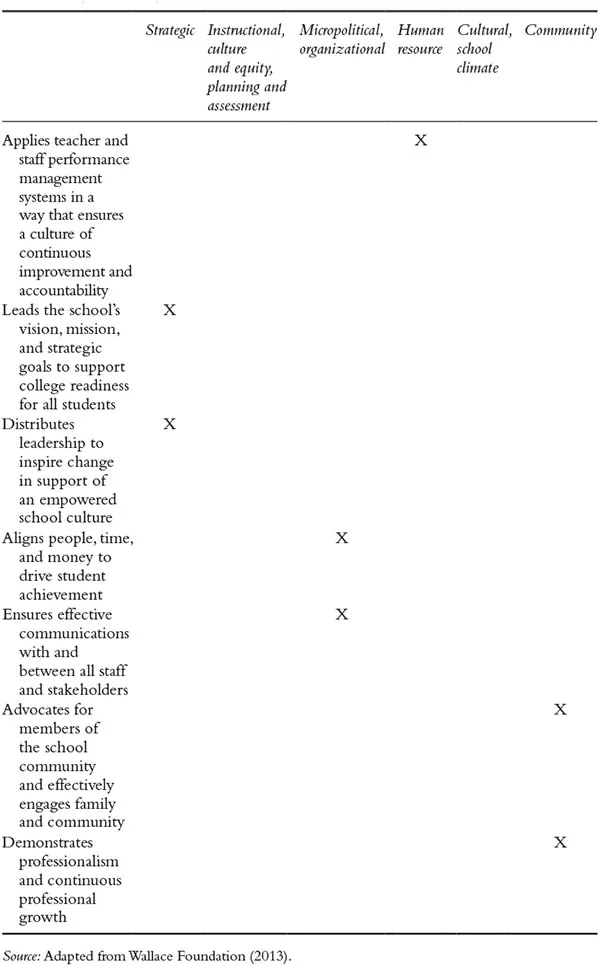

Society, various organizations, and those who study the work of principals hold various beliefs about what principals should do—what roles and responsibilities fall under their job functions. The list is always expanding. Table 1.4 describes some of the work supported by the Wallace Foundation partnership with one school district to broaden the conceptualization of how principals should behave. For additional examples see the Wallace Foundation (www.wallacefoundation.org).

TABLE 1.4 Leadership Standards at One School District

Further, federal and state agencies are not shy about prescribing activities for principals and teachers. These prescribed activities sometimes change abruptly and often radically. For example, in the 1980s it was commonly advocated that principals were instructional leaders (with an emphasis on improving instruction and student learning) and that effective schools were differentiated from less effective schools because of principals’ instructional leadership. Ron Edmonds’ (1982) characterization of effective schools was widely cited. Edmonds’ correlates follow:

- The leadership of the principal characterized by substantial attention to the quality of instruction.

- A pervasive and broadly understood instructional focus and orderly, safe clim...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Being a Principal in an Era of High-Stakes Teacher Evaluation

- 2 Race to the Top and Beyond: The Demand for More Classroom Observation

- 3 What Do We Know about Good Teaching?

- 4 Research on Improving Teaching and Student Achievement: The Role of the Principal

- 5 Considerations for Principals When Working with Teachers to Improve Practice

- Appendices

- Index