Mandates, Jurisdiction, and Laws

Forensic science has its origins in early China and was documented in an early transcript of text, Washing Away of Wrongs by Sung Tz’u written in 1248. He was a criminal affairs officer who wrote the book based on personal experiences. Within the text he described a scenario of a local village murder by a sickle used to harvest grain. The murderer was unknown and the investigator had each farmer bring their tools to the village to be examined. It was noted that flies were attracted to one particular sickle. This was apparently due to adherent tissue and blood on the tool and ended with the farmer admitting to the crime. The story has roots for the basis of forensic entomology with its observation of the relevance of insects and their relationship to the cycle of death. He described handling of male corpses by local men of low social standing and the female corpses were managed by local midwives.

The early Greeks performed anatomical dissections in an attempt to understand the workings of the body and organ relationships. However, it wasn’t until the late 18th century when a book written by Giovanni Morgagni that described autopsy dissections with descriptions of disease processes that they gained acceptance in the West. This served as a framework in the late 19th century for Dr. William Osler, the acclaimed physician and educator, supporting the autopsy as a great teaching method for physicians to learn about their patient’s disease and to see for oneself the disease process. His work and influence served as the basis for medical training that still is in existence today. The period after World War II showed extensive interest in autopsies, and most were done in the hospital setting to gain knowledge about the effectiveness of new treatments, as well as learn about the disease itself. Hospital autopsies were done for approximately 50% of deaths.

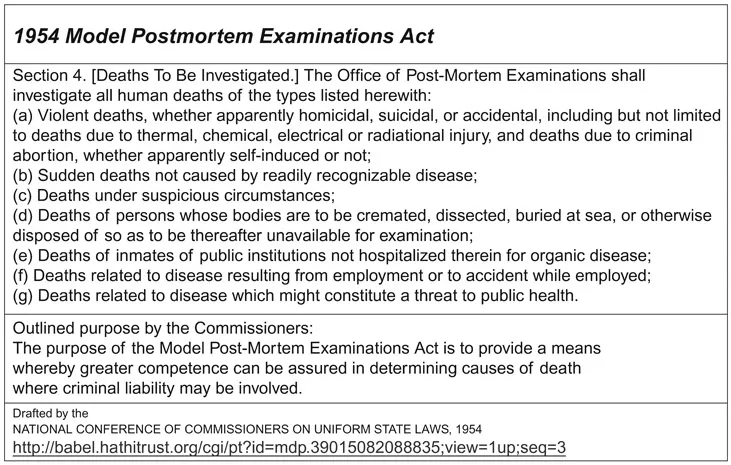

In 1954 the United States passed the Model PostMortem Act, which outlined general classes of deaths that need to be further investigated and certified by a government body rather than a hospital pathologist or treating physician (Figure 1.1). This act was used as a framework for each state to develop its own particular laws regarding death investigation. The act outlines reporting of all violent deaths; unusual, unnatural, or suspicious deaths; all prison deaths; and any death thought to represent a public health hazard. Over the years, each state has modified their laws to adapt to advances in the medicolegal system, but for the most part they read as they were originally written and reflect these guidelines.

Today, it is estimated that hospital autopsies are done in less than 10% of hospital deaths. The decline is related to multiple influences, including the deleted requirement by the Joint Commission of American Hospitals (their accrediting body) for a minimum autopsy rate and reimbursement to the hospital for this service, as well as improved radiologic methods for patient evaluation [4]. The interesting finding, however, is autopsies discover 22–33% findings that were not previously known even with the current technology [4]. They provide answers to families and further understanding to medical science, but unfortunately continue to decline in the hospital community.

FIGURE 1.1 The 1954 Model Post-Mortem outlined the recommended state mandated reporting of cases to a central investigative agency for adoption of individual state laws.

Caseloads for medical examiners and coroner offices continue to increase as the population increases. With shortages of forensic pathologists and limited tax-based funds, death investigation offices must limit autopsies performed to those mandated by law. This creates a void for hospitals and families wishing for answers. Hospital pathologists rarely perform them, and in modern hospitals, morgues are no longer included as an essential area of the laboratory department. Those autopsies not falling under jurisdiction of the state’s death investigation laws require signed family permission to proceed. State laws even outline the family members who may give this permission, usually following the order of spouse, adult children, parents of the deceased, adult siblings, a legal guardian, and then the individual charged with the disposition of the remains.

In the situation of religious objections and deaths falling under the jurisdiction of the death investigator, an autopsy may proceed without family permission. However, it is best for public relations to work with the family and try to abide by their wishes or perform the autopsy within their religious constraints if at all possible. This may require a rabbi to be present during the procedure, collection of all body fluids to return with the body, or particular religious practices to be performed before or after the procedure. Muslim and Jewish religions request burials prior to sundown of the day of death if at all possible. Some religions forbid embalming. Some families request no autopsy because they wish to have an open casket and viewing of the decedent. With education about the procedure, they can be reassured that the incisions will be done in locations that will not preclude viewing, embalming, and open-casket funerals if the body was not damaged extensively by trauma prior to the autopsy. Objections can be overcome with meaningful conversations between the family and the death investigator or pathologist.

There is no universal body governing the death investigation system at a national level, and each state performs death investigations differently from its neighboring state. Many deaths reported to a death investigation office involve sudden death due to unknown mechanism. They represent natural diseases not previously or well documented prior to death, or the treating physician may be unavailable to sign for a patient with a well-documented history. Generally, there is a time limit in which a death certificate needs to be filed with a local health department after death. For this reason, the medical examiner serves as a resource to fill these gaps. The pathologist can issue meaningful causes of death based on medical records and external examination of the body without the need for an internal examination and full autopsy.

The local health department is the governing body that filters all death certificates to the National Bureau of Vital Statistics. They review and numerically code the causes of death into categories so that trends in causes may be recognized to adjust surveillance, prevention, and treatment practices. The local health department also issues burial or cremation permits to funeral homes after a valid death certificate is filed. They supply copies of death certificates, which are usually public record and can be obtained by anyone. The 1992 Model State Vital Statistics Act and Regulations serves as a template for each state to model their vital records practices and can serve as a reference to answer unusual questions when completing a death certificate [12].

The coroner system has been in existence since organized colonization began in 1492 when the concept was imported with the settlers from England. The first medical examiner office was established in New York City in 1918, and it was the first government division of its kind in the United States [5]. They were also responsible for the first toxicology laboratory in 1918 [5]. The first chief medical examiner in the New York office was Dr. Charles Norris. This was followed by New York University establishing the first department of forensic medicine in 1933.

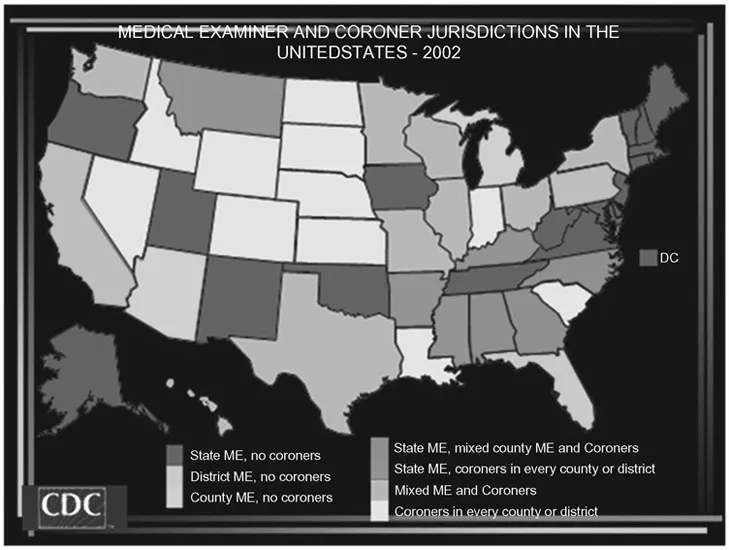

The Center for Disease Control maintains a list of the medical examiner and coroner jurisdictions within the United States, shown in Figure 1.2 [2].

FIGURE 1.2 This map illustrates the various combinations of coroner and medical examiner system jurisdictions within the United States.

History of Criminalistics

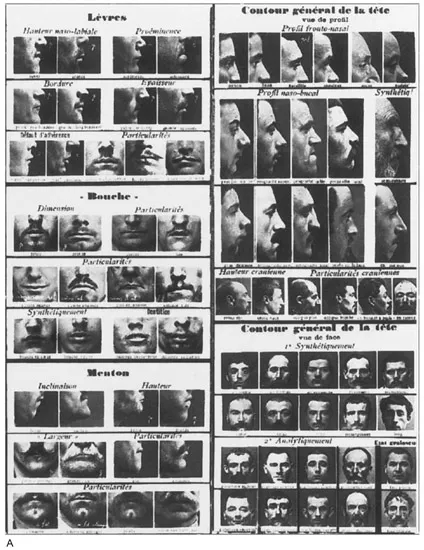

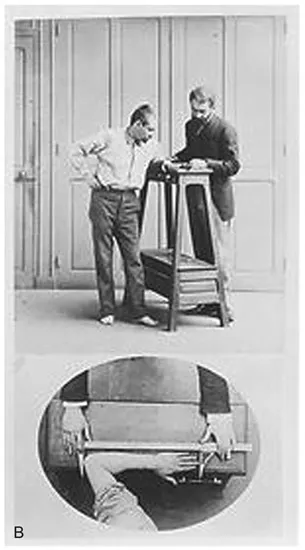

Parallel to the development of forensic medicine and autopsies, the world of criminalistics was also developing and spurring forward the science of evaluating evidence and tracking criminals. Alphonse Bertillon was a French law enforcement officer in the late 19th century who performed research in anthropometry, which is a study of physical characteristics of a person that make him or her unique. His study involved recording measurements of various body regions, such as forearms, trunks, ears, fingers, and faces, to differentiate one person from another (Figure 1.3). This had applications for differentiating criminals from each other, because the usual method had been for station police officers at the entrance to the jail to make visual identifications, which were sometimes inaccurate. The main purpose was to separate repeat-offender prisoners from first offenders. At the time, it was a huge scientific advancement and was thought to be reliable until the early 20th century when it failed to differentiate a case of twins. Although these particular measurements were eventually found to be unreliable, they formed the basis for the science of biometrics that utilizes a similar idea of individualizing characteristics but includes more detailed,

FIGURE 1.3 (A) Various physical characteristics used by Alphonse Bertillon in his research on anthropometry.

(B) An example of the type of measurements he performed to characterize individuals. It shows a striking similarity to our current method of figuring stature from femur bone lengths.

patterned relationships, such as iris scans, fingerprints, and facial-recognition software used in security programs.

Another notable hallmark in criminalistics was the work of Edmond Locard in the early 20th century. He too was a Frenchman but with a background in medicine and law. He became interested in forensics during his studies and eventually formed the first criminalistics laboratory in Lyon, France, in 1910. He is best known for Locard’s exchange principle, which states that whenever two items come into contact they exchange material between them. This is the principle used to recover evidence and particular trace evidence on the body or other items in a crime scene and link it to the individual who left it. The importance of this principle is that no scene is without trace evidence; it is the job of the investigator to locate it and collect it. Locard was also extremely interested in fingerprints, and through his work in microscopy, he detailed characteristics of them that are used today in fingerprint identification. He is generally considered the first criminalist.

In 1923, August Vollmer, chief of the Los Angeles, CA, Police Department, established the first American crime laboratory. The second crime laboratory was established in 1929 by Calvin Goddard (well known for his work in ballistics) at Northwestern University in Chicago, IL.

Coroners

Coroners are elected officials and in most jurisdictions the only credentials required for being placed on the ballot are a high school diploma and a voter registration card. Medical, science, or law enforcement background is not required. In some jurisdictions, the position has been combined with the sheriff ...