![]()

Chapter 1

Young children in a digital age

Lorraine Kaye

Introduction

This chapter will consider developments in technology, particularly mobile and touchscreen technology, and how they impact on children’s lives and the implications for teaching and learning in the early years. Particular reference is made to how technology supports constructivist learning theory. According to a constructivism paradigm, learning is an active process where children construct meaning out of the information being presented (Oluwafisayo, 2010). The relationship between sociocultural context and the use of technology in the early years will also be considered.

Developments in technology

The rate at which technology develops is exponential. The ability to produce more powerful and faster processors for use in smaller and more affordable devices has led to the proliferation of smartphones, tablet computers and other ultra-portable devices, which are all becoming a part of everyday life. This is due, in part, to global developments in connectivity to the internet through broadband and wireless networks.

Recent statistics (Office for National Statistics, 2014) show that 21 million households in Great Britain had an internet connection, which represents 83 per cent of households, up from 80 per cent in 2012. The statistics indicate that internet access varies depending on household composition, with almost all households with children having an internet connection (97 per cent).

The UK’s first 4G mobile network was launched in October 2012 offering faster access anywhere and it continues to expand rapidly. Recent developments have not only been limited to mobile broadband, with the availability of wireless broadband (wifi) hotspots increasing at a rapid rate. The availability of both mobile broadband and wifi networks means the mobile internet is now used by more people than ever before and the way households connect to the internet has changed considerably in recent years. Dial-up internet has almost entirely disappeared from Great Britain’s internet map, with less than 1 per cent of households still connecting this way.

Touchscreen technology

Alongside the development of the speed and ease of internet access has been the development of more accessible and more mobile devices. As the use of mobile phones with internet access has grown, a myriad of features and applications have also been developed to meet demand and harness the availability of the broader range of connectivity options outlined above. The smaller screen size of earlier mobile phones made some of the text quite difficult to read and/or it was necessary to keep scrolling the text using a keypad in order to access information. The rapid advancement of touchscreen technology in the 2000s enabled easier and faster access to the information on the screen. In 2007 Steve Jobs demonstrated the first swipe-to-scroll iPhone, which has led to the development of a plethora of ‘smart’ devices: ‘Generally speaking, if a machine/artefact does something that we think an intelligent person can do, we consider the machine to be smart’ (Walter Derzko, n.d.). Smartphones and other smart devices now offer instant messaging, sending and receiving of email, satellite navigation, productivity applications (word processing, etc.) and games among the huge range of applications available.

Although more mobile computer devices were available from the late 1990s in the form of tablet devices, where the screen sat on top or swivelled around a smaller keyboard, the developments in mobile phone and touchscreen technology have led to a new generation of tablet devices. These are thinner and lighter and it is predicted that tablet sales will exceed traditional personal computer (desktops, notebooks) sales in 2015 (Gartner Inc., 2014).

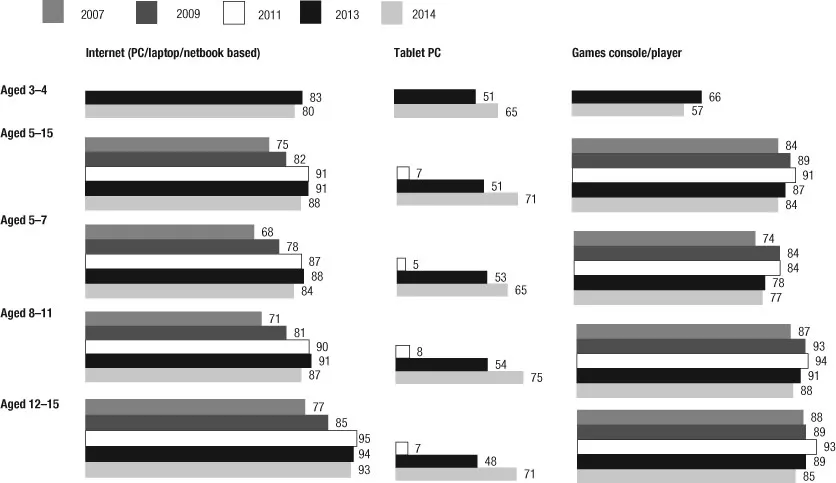

Young children’s access to the internet

In the UK, eight in ten children aged three to four live in a household with access to the internet through a PC, laptop or netbook (see Figure 1.1 below). Two-thirds of children aged three to four (65 per cent) live in a household with a tablet computer in the home, an increase since 2013 (from 51 per cent) (Ofcom, 2014).

The recent inclusion of children aged three to four years in the Ofcom statistics above, reflects the growth in the number of pre-school children using these devices to go online. They and most babies under the age of two in developed countries now have an online presence (or digital footprint). It could be argued that some may have a digital ‘footprint’ even before they are born (see Figure 1.2).

Younger children who go online at home, in particular, are five times more likely than in 2012 to use a tablet computer; and one in eight three- to four-year-olds use a tablet computer to go online (12 per cent). Games are the most commonly mentioned online activity carried out at least weekly by the majority of three- to four-year-olds (58 per cent). One-quarter of this age group watch TV at home using an alternative device, and 20 per cent use on-demand services. One in seven parents of three- to four-year-olds feel their child knows more about the internet than they do (Ofcom, 2014).

Figure 1.1 Availability of key platforms in the home by age: 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013 and 2014.

Figure 1.2 Scan of my unborn grandson, downloaded from Facebook.

Within Europe, between 50 per cent (Germany) and 78 per cent (Netherlands) of pre-school children access the internet. This is also reflected in other developed countries. For example, in South Korea 93 per cent of three- to nine-year-olds go online for an average of eight to nine hours a week (Jie, 2012). In the US, 25 per cent of three-year-olds go online daily, rising to about 50 per cent by age five and nearly 70 per cent by age eight (Gutnick et al., 2011). In Australia, 79 per cent of children aged between five and eight years go online at home (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2012; Holloway et al., 2013). In some developing countries, large numbers of learners are moving directly to mobile devices, bypassing the personal computer stage.

More recently, smaller tablets, such as the mini iPad have appeared on the market while the screens of newer smartphones have increased in size. This has led to the development of ‘phablets’. These are smartphone–tablet hybrids, with screen sizes between five and six inches, that offer the portability and functionality of a smartphone crossed with the larger touchscreen experience of a tablet. It has been suggested that ‘phablets could become the dominant computing device of the future – the most popular kind of phone on the market, and perhaps the only computer many of us need’ (Manjoo, 2014).

Therefore, developments in technology have seen the explosion of a multitude of other digital media including games consoles, e-readers and televisions; and touchscreen technology has become part of our everyday lives: ‘Once a futuristic novelty, it’s now expected in everything from music players to printers, train ticket machines to supermarket self-checkouts’ (The Guardian, 2015).

A digital age: Social and cultural contexts

Socialisation and environment each have a large impact on how one thinks about, interacts with, and views the world. This … requires us, as educators, to respond to the current techno-social conditions that our students experience.

(Poore, 2013)

Figure 1.3 A child’s digital environment.

The prevalence of digital media in children’s lives (see Figure 1.3) has led to a change in the way in which children engage with technology. Children (and adults) of all ages are spending an increasing number of hours per week in front of different kinds of digital media which they can control and interact with in an instinctive way, and usually through the use of touchscreens.

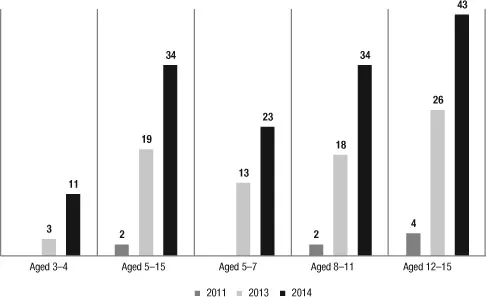

Figure 1.4 Tablet access, use and ownership, by age of child, 2011, 2013.

Access to a tablet computer in the home in the UK has more than doubled since 2012, with this increase seen for all age groups of children and for all socio-economic groups. (see Figure 1.4 above). These statistics are backed up by qualitative evidence and anecdotal experiences. For example, a father recently told me that his three sons, aged five, seven and ten years, each have their own tablets and use them to play games with each other or to discover information on the internet. ‘When the little one cannot keep up, he simply uses the voice recognition feature to access the information that the other two search for.’ He explained that the children often sat in different rooms with their devices playing games against each other.

Sociocultural theory

Sociocultural theory asserts that children acquire and master the cultural tools of their situations (Göncü and Gaskins, 2011). Effective modelling and scaffolding of the meaningful use of tools provides opportunities for children to practise and hone their skills. ‘This seems to be what is happening in families and so an infant who is able to unlock an iPhone™ or a toddler who turns on a computer to access an online game should be seen as participating in viable cultural activity’ (Edwards, 2013).

A recent study from Stirling University’s School of Education found that the family’s attitude to technology at home is an important factor in influencing a child’s relationship with it. The study concludes:

The experiences of three to five-year-olds are mediated by each family’s distinct sociocultural context and each child’s preferences. The technology did not dominate or drive the children’s experiences; rather their desires and their family culture shaped their forms of engagement.

(Adey et al., 2013)

Research by Plowman et al. (2012) also suggests that adults and other more able partners, such as older siblings, have a critical role in developing children’s learning with computers and other digital media. This can be by showing children how to use a device or by showing interest, asking questions, making suggestions or just being there. Adults may also be unaware that their own use of digital media provides support as children learn by watching and copying. The term used to describe these various ways of providing support for learning with technology is ‘guided interaction’.

Plowman et al. (2012) further suggest how interactions with technologies could support four main areas of learning at home:

- ■ Operational learning – learning how to control and use technologies, getting them to do the things you want them to do and having opportunities to make your own inputs and get a personalised response.

- ■ Extending knowledge and understanding of the world – by finding out about people, places and the natural world.

- ■ Dispositions to learn – as they become increasingly competent users of digital media, children show greater concentration and persistence and their self-confidence and self-esteem flourishes.

- ■ The role of technology in everyday life – as they observe adults involved in a wide range of pursuits children learn that technology provides opportunities to design things, order goods, research travel and send text messages, even though they themselves cannot yet undertake these activities.

Access to technology

In households where this technology is accessible, children under five years old appear able to use smartphones, tablet computers and games consoles almost intuitively, swiping screens and confidently pressing buttons, something I have witnessed with my four-year-old grandson. ‘Even in low technology households, the home often provides a richer mix of technologies than many pre-school settings as well as providing opportunities for children both to observe and to participate in authentic activities’ (Plowman et al., 2010).

Therefore, young children will arrive at early years settings with varying degrees of understanding of how to operate digital technologies; many of them are able to access, manipulate and interact with a range of websites and applications. However, just as there is a concern about the differences in access to print media for children from a range of differing social, economic and cultural backgrou...