![]() Part I

Part I

Introduction![]()

1

International Achievement Testing, Education Policy, and Large-Scale Reform

Louis Volante

Introduction

The global educational reform movement implies not only convergence but also coordination through various world agencies based on standardization, choice, competition, and data-driven accountability (Peters & Besley, 2014). In the realm of primary and secondary education, the latter has been manifested through the widespread adoption of various standards-based reform models that couple curriculum standards and large-scale assessment programs as the primary lever to spur improvements in the overall quality of an education system (Volante, 2012). Teachers, administrators, and policymakers working within standards-based reform contexts are often compelled to make refinements to their practice to improve student learning and ultimately a nation’s intellectual capital—the collective achievement of their elementary and secondary students. The latter may be mandated through curricular reforms and is further bolstered by the inundation of popular media reports that discuss the decline of educational standards—as measured by large-scale assessment programs (see Alphonso, 2014; Andrews et al., 2014; Dillon, 2010; McMahon, 2014; Rich, 2014). Establishing and measuring the attainment of student achievement standards in core curriculum areas such as reading, writing, mathematics, and science is intended to provide the necessary impetus to facilitate large-scale education system reform. Student achievement data across schools, districts, states/territories/provinces, and countries internationally can be compared and contrasted, acting as a lever to inform education policy formation, strategic planning, and ultimately education governance issues. Advocates of standards-based reform argue that large-scale assessment programs provide valuable and necessary information to assist in the revision of national evaluation systems, curriculum standards, and performance targets.

Standards have traditionally been measured in relation to regional and national large-scale assessment programs. These programs have been criticized across a range of education jurisdictions for leading teachers, particularly in low-achieving schools and districts, to narrow the curriculum and emphasize basic rather than critical thinking skills (Berliner, 2011; Black & Wiliam, 2005; Crocco & Costigan, 2007; Duke, 2013; Griffin, McGaw, & Care, 2012; Menarechova, 2012). The education research literature has suggested that students become less motivated and are more prone to drop out in education contexts that utilize large-scale assessments for high-stakes decisions (Assessment Reform Group, 2002; Glennie, Bonneau, Vandellan, & Dodge, 2012; Kern, 2013). Large-scale assessment programs have also been criticized for being culturally biased, placing minority students at a disadvantage (Solomon, Singer, Campbell, Allen, & Portelli, 2011; Stobart, 2005; Thompson & Allen, 2012). Collectively, these criticisms are often referred to as the “unintended” negative consequences of regional and national large-scale assessment programs. Far less is known about the impact of international achievement testing programs across a range of political, economic, cultural, and educational contexts.

International Achievement Testing Programs

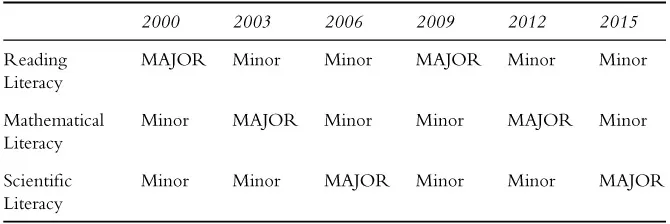

Since the initial administration of the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) in 1995, the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2000, and the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) in 2001, international achievement testing programs have steadily grown in global importance. PISA is administered by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and includes assessments of three “life skills” domains: reading literacy, mathematical literacy, and scientific literacy. These three domains are assigned a major testing domain on a rotating format, and as a result, are examined in greater detail. Table 1.1 summarizes the timelines for major and minor literacy emphases since the inception of the PISA survey in 2000.

Table 1.1 Chronology of Major and Minor Literacy Domains on the PISA Survey

In addition to the major and minor literacy domains, the OECD notes that PISA regularly introduces new tests to assess skills relevant to modern society, such as creative problem solving and financial literacy (introduced in 2012) and collaborative problem solving (introduced in 2015).

According to the OECD, this triennial survey “assesses the extent to which students near the end of compulsory schooling have acquired key knowledge and skills that are essential for full participation in modern societies” (OECD, 2014a, p. 1). The most recent administration of PISA in 2015 included students from more than 70 economies. Given the scale of PISA, it is not surprising that it has been referred to as “one of the largest non-experimental research exercises the world has ever seen” (Murphy, 2014, p. 898). Of the three established international achievement testing programs, PISA attracts the greatest attention globally in policy spheres. For their part, the popular media has bolstered the prominence of PISA by likening it to the “Olympics of education” (see Alphonso, 2013; Petrelli & Winkler, 2008; Scardino, 2008). The perceived prominence of PISA is an issue that will be addressed in greater detail in the national profiles reported in this edited volume.

The International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) is responsible for three different international achievement testing programs: TIMSS, PIRLS, and ICILS. TIMSS measures trends in mathematics and science achievement at the fourth and eighth grade levels. TIMSS Advanced, which is scheduled for 2015, is a new measure of advanced mathematics and physics for students in their final year of secondary school. PIRLS measures trends in reading comprehension at the fourth grade level. More recently, PIRLS was expanded in 2011 to include prePIRLS, which was developed to represent a less difficult version of the traditional PIRLS survey. The most recent administrations, TIMSS 2011 and PIRLS 2011, featured 52 and 48 participating countries, respectively. ICILS refers to the International Computer and Information Literacy Study, which measures eighth grade students’ Computer and Information Literacy (CIL). According to the IEA, CIL refers to an individual’s ability to use computers to investigate, create, and communicate in order to participate effectively at home, at school, in the workplace, and in the community. The initial administration of ICILS took place in 2013 and included 20 countries. The international database and technical report is scheduled for release in March 2015. Thus, it would be premature to comment on the impact of this measure, particularly since it is a very recent addition to the international landscape.

Policy Research, Support, and Guidance

All international achievement testing programs collect contextual information on the learning conditions of students and are devised to shed more light on the complex interrelationships between social, cultural, economic, and educational factors associated with student achievement. These contextual surveys are meant to help policymakers identify student, classroom, school, and national variables associated with student achievement. Both the OECD and IEA make positive statements on their respective websites on the utility of these international benchmark measures and their associated contextual surveys for informing national education policy decisions. For example, the OECD states that the PISA survey allows educational jurisdictions to evaluate education systems worldwide and provides valuable information to participating countries so they are able to “set policy targets against measurable goals achieved by other education systems, and learn from policies and practices applied elsewhere” (OECD, 2014a, p. 2).

Similarly, IEA suggests that TIMSS and PIRLS can be used by participating countries in “various ways to explore educational issues, including: monitoring system-level achievement trends in a global context, establishing achievement goals and standards for educational improvement, stimulating curricular reform, improving teaching and learning through research and analysis of data, conducting related studies, and training researchers and teachers in assessment and evaluation” (TIMSS and PIRLS International Study Center, n.d., para. 2). Nevertheless, the degree and nature of influence these international achievement tests exert on education policy formation and global education governance remains highly contested, particularly for the PISA triennial survey, which has assumed priority status (see Kamens, 2013; Meyer & Benavot, 2013a; Pereyra, Kotthoff, & Cowen, 2011; Pons, 2012; Sellar & Lingard, 2013).

In order to support and provide guidance to policymakers, the OECD provides resource documents that outline many of its research activities and analysis of findings. Its online library, which is easily accessible, contains a number of series such as PISA in Focus, which provides “concise monthly policy-oriented notes designed to describe a PISA topic” (OECD, n.d., para. 1). These research briefs provide policymakers with comparative data and conclusions that address complex questions such as Who are the strong performers and successful reformers in education? (No. 34), When is competition between schools beneficial? (No. 42), and Does performance-based pay improve teaching? (No. 16). To date, there have been 61 issues of this newsletter published.

Although less frequent and numerous than PISA in Focus, the IEA also publishes policy briefs related to TIMSS and PIRLS. These briefs are similar in nature to those of the OECD, albeit twice as long at approximately eight pages each. According to the IEA, “each publication in the series aims to connect study findings [from the TIMSS and PIRLS studies] to recurrent and emerging questions in education policy debates at the international and national level” (IEA, 2011, para. 1). Past titles in this small series include Does increasing hours of schooling lead to improvements in student learning? (No. 1) and Is participation in preschool education associated with higher student achievement? (No. 2). Collectively, the series published by OECD and the IEA provide policymakers with specific suggestions for future policy reform.

Despite their stated promise for informing the future trajectory of national education policies, not everyone is convinced that the achievement testing or policy support provided by the OECD and IEA have a beneficial impact on education systems around the world. In particular, a significant segment of the academic community has expressed concern over the expanding role of international achievement testing and has questioned the nature and scope of policy decisions that flow from an emphasis on benchmark testing programs such as PISA, TIMSS, and PIRLS (see Baird et al., 2011; Benavot, 2012; Carnoy, 2015; Corbett, 2008; Kamens, 2013; Meyer & Benavot, 2013a; Supovitz, 2009). Some have gone so far as to suggest that international achievement testing programs such as PISA are damaging education worldwide by escalating testing, emphasizing a narrow range of measureable aspects of education, and shifting educational policies to find “short-term fixes” designed to help a country climb in the rankings (Andrews et al., 2014; Meyer & Zahedi, 2014). In this way, critics underscore predictable and unintended negative consequences that follow national fixations with international achievement test results. Discovering whether these programs are a valuable tool to inform education policy formation and governance (Bernbaum & Schuh Moore, 2012; Morgan, 2009) or a negative focus that misdirects education decision-making (Goldstein, 2014; Meyer & Benavot, 2013b) is an important area of inquiry and a key analytic focus of this edited volume.

Policy Responses: A Preliminary Review

International achievement testing programs highlight the educational differences that exist across national education systems, and policymakers around the world are increasingly motivated to keep up with competitive standards within the global community (Duncan, 2014; Morris, 2011; OECD, 2013a; Sellar & Lingard, 2013). In Europe, one-third of countries have indicated a demand for more information on curriculum and teaching as a consequence of their results on international assessment programs such as PISA and TIMSS (Eurydice Network, 2009). PISA, in particular, has been described as an influential tool in governing the European education space (Grek, 2009). In the United States, consistent performance below the OECD average on PISA has provided a rationale to intensify testing to improve school outcomes and/or adopt reforms that emulate other high-performing educational systems (Mathis, 2011; Turgut, 2013; Wang, Beckett, & Brown, 2006). In Canada, the relative performance of provinces, curriculum renewal, and geopolitical forces are associated with the nature and degree of policy responses to international achievement testing programs (Volante, 2013).

In Asia, high-achieving educational jurisdictions such as Shanghai-China, Hong Kong-China, Singapore, Japan, and South Korea, which secure the top international scores in reading, mathematics, and science, serve as models to be emulated in other parts of the world—what is more broadly noted as the policy-borrowing and/or transfer effect in education (see Carvalho & Costa, 2014; Grek, 2009; Ringarp & Rothland, 2010; Steiner-Khamsi & Waldow, 2012). Even developing countries such as Brazil are increasingly turning to international achievement testing programs, such as PISA, to both identify problems and drive their education reform initiatives (Bruns, Evans, & Luque, 2011). Many countries around the world, particularly those faced with lackluster results, are embarking or already engaged in significant lar...