![]()

Part I

The state of democracy

![]()

1

Democracy and Democratisation in Post-Communist Europe1

Andrew Roberts

Few areas of post-communist politics have been studied as intensively as the fate of democracy and in few areas has the conventional wisdom shifted as radically – from initial joy at the fall of communism, to pessimism about the legacies of the past, to optimism again with entry into the European Union, and finally to more qualified assessments today. As Kitschelt (2003) points out, no other region in the world has as diverse and I would add shifting regime outcomes. Whenever things seem to stabilise, new events inevitably shake up received understandings.

Given the diversity of outcomes and the amount of research on the region, this review will inevitably be partial.2 Nevertheless, I will attempt to cover what I consider the seminal and most influential theories of the collapse of communism, regime outcomes, and the consolidation and quality of democracy.

I will start with a brief description of the key facts about democracy which include the dramatic and unpredicted shift in politics in 1989 and the subsequent “return to diversity”. I then turn to explanations for the fall of communism where I discuss both the standard account which emphasises a loss of legitimacy and the power of civil society as well as more complete theories that outline the micro-mechanisms of collapse and put weight on tipping points and organisational bank runs. I briefly digress to address allegations that scholarship on the region failed for not being able to predict the collapse.

The heart of the chapter discusses theories of regime outcomes – why some countries became democratic and others authoritarian. Many of the early responses to the changes emphasised proximate factors related to the course of the transition such as elite bargaining, the outcomes of initial elections, and external influence. However, recently a consensus has started to emerge that these factors have deeper roots in communist and pre-communist legacies including socioeconomic modernisation, education, religion, and ethnic divisions.

I consider separately recent shifts in regime outcomes – particularly the colour revolutions as well as democratic backsliding – and whether their causes are different from the causes of the initial transitions. I also discuss the appearance of hybrid regimes that have found an equilibrium in between democracy and autocracy.

After considering these regime outcomes across the region, I turn more specifically to the countries of East Central Europe. Here I assess the multiple dimensions of democratic consolidation and the finding that democratic endurance coexists with weak civic engagement and institutional shortcomings. Finally, I turn to the various conceptions of democratic quality and the contrast between the surprisingly positive evaluations that have emerged from scholars and the negative perceptions of most citizens. The chapter concludes with research frontiers.

Simple facts

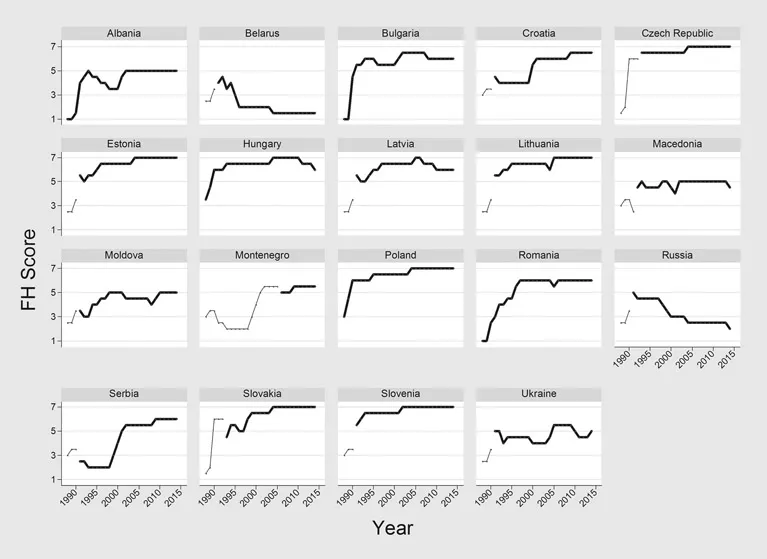

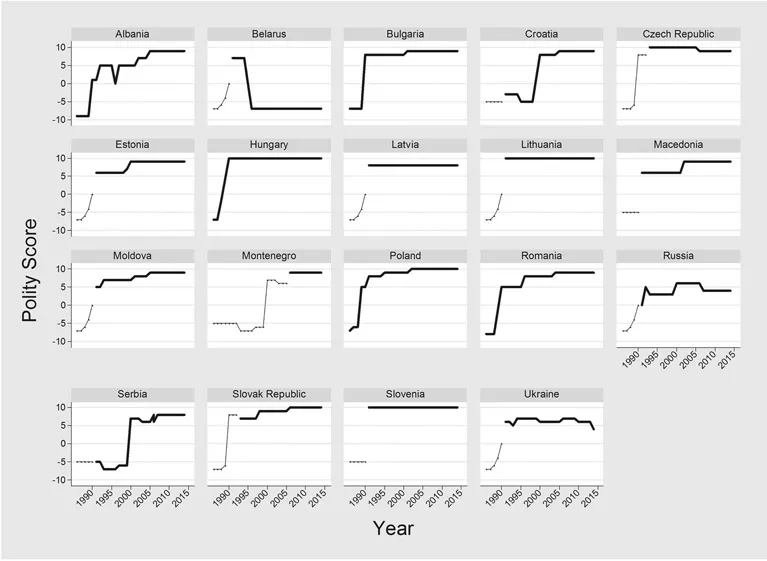

To set the stage for the following sections, I begin with a few simple facts about democracy in the post-communist region. Figures 1.1 and 1.2 present these facts graphically. They show the Freedom House and Polity ratings of democracy in the region from the late 1980s to 2014. For new countries, their scores are linked to the scores of the countries from which they declared their independence. Three facts stand out.

First, countries in the communist bloc were among the most undemocratic in the world up to nearly the moment of transition. They shared more or less the same political system led by a communist party that held all power in politics and the economy. Human rights existed in name only and elections were always a charade. Despite retreating from the brutality of the Stalin era, few had truly liberalised. Poland, Hungary, and Yugoslavia were the states that stood out as somewhat more permissive in their treatment of civil society and independent economic initiatives, but even they still outlawed genuine opposition and fell short on standard measures of democracy.

Figure 1.1 Freedom House scores

Note: These scores represent the average of Freedom House’s political rights and civil liberties scores. I have reversed the direction of the scores so that 7 represents most free and 1 least free. Thin lines indicate scores for the predecessor country and thick lines the successor country.

Second, there was a swift, radical, and unpredicted shift in the politics of the satellite states in 1989 as the individual communist parties surrendered their monopoly on power. Poland was the leader, holding semi-free elections in June 1989. Their example was quickly followed by the end of communist hegemony in Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania, with Yugoslavia and Albania joining along the way. Communist rule gave way soon afterward in the Soviet Union, which broke apart in 1991. Given the dismal status quo in the region, these changes almost always led to substantial democratisation with the exception of the new Central Asian states, which are not covered here.

Figure 1.2 Polity scores

Note: Polity scores range from +10 (most democratic) to −10 (most autocratic). Thin lines indicate scores for the predecessor country and thick lines the successor country.

Third, after this rapid change, the outcomes of these transitions were widely divergent. Indeed, the regime outcomes are arguably the most diverse of any region in the world. A number of states in the region very quickly became almost complete democracies, meaning that they received nearly the highest possible assessments from organisations like Freedom House and Polity. These states were largely on the western border of the region and include Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Slovenia. Another group, largely on the eastern side of the region, barely budged from their undemocratic heritage; this group includes just about all of Central Asia (with the exception of Kyrgyzstan). Meanwhile, a number of countries had bumpier paths. Some experienced substantial problems but ultimately joined the first group, a pattern that describes Slovakia, Croatia, Serbia, and Romania. A few of these – Albania, Macedonia, Moldova, and Ukraine – settled at a lower level of democracy or as hybrid regimes. Another group meanwhile looked to be democratising early in the transition but then fell back into a resolutely non-democratic equilibrium. This path applies to Belarus, Russia, and the Caucasus. In short, democracy has evolved in different ways across the region.

The fall of communism

Why did communism fall?3 The conventional wisdom about mechanisms goes something like this (see, for example, Chirot 1990–91; Dallin 1992): economic decay in the 1970s and 1980s undermined the legitimacy of the regimes which was premised on providing better living conditions. This in turn prompted leaders, particularly Gorbachev, to engage in reforms like glasnost and perestroika (Brown 1996; Almond 1999). These reforms failed because they did not address the fundamental problems of the economy (Kornai 1992). Their failure undermined the confidence of the regime and encouraged civil society. It was at this point that people power brought down the regime (Tismaneanu 1992). Interestingly, very few scholars mention the explanation most common among the lay public: Reagan’s military build-up.

But as Kalyvas (1999) points out, there is a large difference between decay – which can last for a long time – and breakdown. More specifically, dissatisfaction by itself could not overthrow the regime; genuine civil society as opposed to mass demonstrations played a small role in the actual revolutions (Solidarity in Poland would be the exception), and reformers like Gorbachev believed in communism to the very end. Indeed, while external observers were acutely aware of stagnation, most saw more important sources of stability.

A number of scholars have thus tried to propose stronger mechanisms for the collapse. Most prominent has been Bunce (1999). Her argument is that communist institutions were subversive – they at once created a unified public and divided elites. The institutions of communism homogenised citizens by giving them similar socio-economic positions and thus similar interests. For Bunce, it is no surprise that communism gave birth to a movement calling itself Solidarity. This explanation, however, only goes halfway because it does not account for the timing of the collapse. Bunce thus turns to a second process – borrowed from social movement theory – changes in the political opportunity structure. During the 1980s, a number of events combined to give the public the space to overthrow the regime. Specifically, leadership succession crises, the introduction of “great reforms” like perestroika, and the opening up of the international system gave citizens the opportunity to make 1989 an annus mirabilis.

A number of scholars have gone even deeper into the micro-mechanisms of these dynamics. On the elite side, a key work is Solnick’s (1999) Stealing the State. He argues that Gorbachev’s reforms exacerbated the weakness of bureaucratic control in the Soviet Union. As central direction declined, bureaucrats began to appropriate organisational assets for their own purposes, and this theft hollowed out the regime. Feedback effects accelerated the process as insiders grabbed what they could, lest they be left with nothing. Solnick calls this an “organisational bank run”, and it undid the power of the communist regime over the economy and the country. Roeder’s (1993) Red Sunset shows further how the form of the Communist Party made adaptation difficult. Reforms forced the party into competition, but it did not know how to compete. Members were so used to obeying orders from above that they had difficulty responding to criticisms from new actors.

But the elite side does not provide a full explanation. Even a weakened communist party over-awed the small and disorganised dissident groups that existed; the dissidents more than anyone were aware of this power differential. Somehow a push from the public at large would be needed.

It is hard to ignore the role of nationalism in providing this push. Most of the transitions in the region involved some form of national liberation – whether it was escaping from the yoke of external domination in the case of the satellite states, or breaking free from a perceived dominating nationality in the case of the non-central republics of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia.

Beissinger (2002) focuses on the process of collective mobilisation in the Soviet Union that led to declarations of sovereignty. He argues that structural features mattered – nationalities with better institutions, more resources, and larger grievances were more likely to mobilise – but, after studying some 6,000 events, he finds that these events created their own momentum. There were tides of protest and early movers influenced later ones, so that by the end even the least well-situated groups were carried along on the wave.

These theories still have trouble explaining the individual-level calculations leading to the collapse because active protest carried significant risks and coordination was difficult. The main solution here is to invoke tipping point dynamics. Kuran (1991) argues that in deeply repressive regimes like the Soviet bloc, citizens are fearful of expressing their true opinions; they engage in preference falsification. While dissatisfaction with the regime may have been widespread, citizens never knew what their neighbours were thinking, and the regime exacerbated the problem by forcing citizens to publicly express their support for communism and exerting strict control over the media. Kuran argued that such situations are likely to lead to cascades and tipping points – when enough people gathered on the streets, others would follow (see also Lohmann 1994). So what was necessary was for enough people to go out without being arrested or shot. This happened with the loosening of controls and one-off focal events like the attack on a regime-sponsored parade in Czechoslovakia.

These effects played out equally at the international level. Once the opposition in Poland was able to secure relatively free elections without a crackdown or Soviet intervention, this emboldened the Hungarians, whose success in turn inspired the East Germans and so on. Garton Ash (1990: 78) memorably described these demonstration effects or snowballing in a remark to Václav Havel: “In Poland it took ten years, in Hungary ten months, in East Germany ten weeks: perhaps in Czechoslovakia it will take ten days!” His prediction was more or less correct, and Bulgaria and Romania completed the process about as quickly.

The unpredicted and unpredictable collapses

Were these revolutions inevitable and thus predictable? Few scholars saw the fall of communism coming and of those who arguably did, none thought it would come as early as 1989. Despite widespread acknowledgment of stagnation and decay in the 1970s and 1980s, the dominant emphasis in the literature, even as Gorbachev introduced glasnost and perestroika, was on the stability of these regimes.

The failure of the scholarly community to foresee the revolution has been used to criticise political scientific approaches to the region and to politics in general. Some argued merely that it reflected a widespread inability of experts to predict (Tetlock 2006), while others saw it as an indictment of the methods of normal social science (Gaddis 1992/93; Hopf 1993).

However, while the pre-revolution study of the region surely had its problems, the failure to predict these revolutions is not necessarily a symptom of the failures of social science or area studies. The reasons are both theoretical and practical.

Theoretically, although prediction is an important goal of social science and theories should ultimately be judged by their predictive accuracy, social science should not be held to the standard of making predictions of the form: event X will happen at time Y. Social scientists are not soothsayers. Popper pointed out...