eBook - ePub

Coasts for People

Interdisciplinary Approaches to Coastal and Marine Resource Management

- 372 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Coasts for People

Interdisciplinary Approaches to Coastal and Marine Resource Management

About this book

Issues of sustainability and increased competition over coastal resources are changing practices of resource management. Societal concerns about environmental degradation and loss of coastal resources have steadily increased, while other issues like food security, biodiversity, and climate change, have emerged. A full set of social, ecological and economic objectives to address these issues are recognized, but there is no agreement on how to implement them. This interdisciplinary and "big picture book" – through a series of vivid case studies from environments throughout the world – suggests how to achieve these new resource management principles in practical, accessible ways.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Coasts for People by Fikret Berkes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

THE ONGOING AGENDA

A new form of interdisciplinary and adaptive science is required for the coast. Such a science requires both an understanding of global environmental processes and their regional and place-specific manifestations, and also fundamental advances in our ability to address self-organization, resilience and nature– society interactions.

(Brown et al. 2002, p. 2)

At the beginning of the 21st century, the management authority faces a much more complex task than it did 60 years ago . . . Bio-ecological objectives are broader. Social and economic objectives, measures and constraints are more formally recognized . . . The extension of EEZs puts 90 percent of the world resources under national jurisdiction, turning de facto global commons into national commons ready for further reallocation.

(Garcia and Cochrane 2009, p. 452)

The Context

Almost half of the world’s population lives in coastal areas and depends directly or indirectly on coastal resources. Coastal ecosystems are among the most diverse environments on the planet and are critically important for their role in supporting human well-being (MA 2005a). Societal concerns about environmental degradation and loss of coastal resources, livelihoods and values have steadily increased, and other issues, such as food security, biodiversity conservation and climate change, have emerged. Hence, management agencies face a much more complex task than they did in the middle of the last century, especially with the extension of national jurisdictions into the sea to incorporate Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). As a consequence, the education of resource managers is under revision and reorganization, to include the complexities of resource use and social considerations.

As well, there is much interest in civil society in resources and environment, as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), user organizations and various interest groups have become part of governance. These organizations have a major say in decisions; citizen science is on the rise. Influenced by new fields and theories such as commons and resilience, management is no longer top-down, under the control of technical experts. It has become participatory, responding to multiple needs and problems and accommodating an increasingly broader set of objectives and interests. A full set of social, ecological and economic objectives are formally recognized, but there is little agreement on how to implement them.

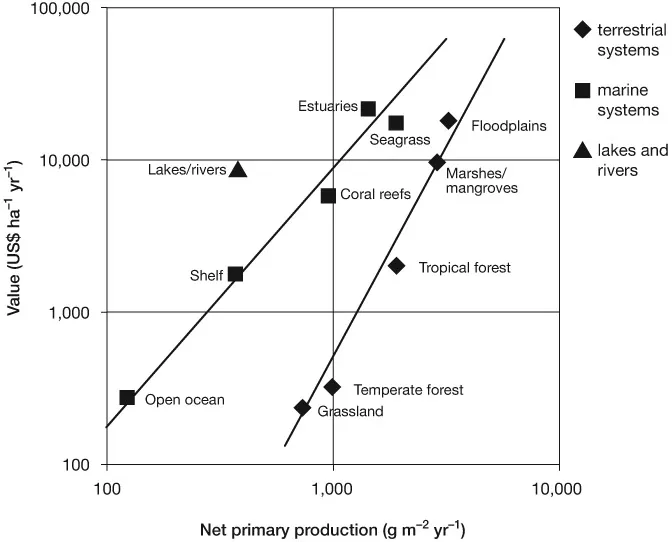

Part of the context is that coastal resources are uniquely valuable and are coming under increasing pressures that lead to loss and degradation. Costanza and colleagues (1997, 1998) estimated the economic values and the net primary production (a measure of biological productivity) of different kinds of ecosystem. Based on these calculations, Figure 1.1 shows that economic values and biological productivity correlate well. The figure further shows that coastal ecosystems such as estuaries, seagrass beds, floodplains, marshes and mangroves tend to be high in both value and bioproductivity, compared with other types of ecosystem. Such data should be used with caution, as some of these environments intergrade into one another. Boundaries of coastal ecosystems are not simple but complex and forever changing. This volume interprets the “coast” rather broadly: we are dealing with a strip of water and a strip of land along this changing boundary (for detailed definitions, see Chapter 7). As well, the volume recognizes the commonalities of saltwater and freshwater environments and uses, to extend the concept of coast to include some major lake and river systems, such as the Mekong and the Amazon and their associated wetlands and floodplains.

Figure 1.1 A comparison of economic and ecological values of coastal ecosystems and other kinds of ecosystem

Source: Brown et al. 2002; data from Costanza et al. 1998. Reprinted with permission

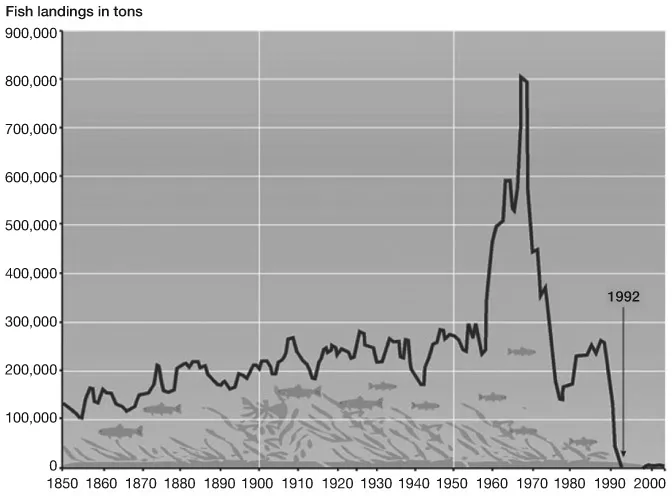

Everywhere in the world, coasts of saltwater, freshwater and mixed ecosystems (e.g., estuaries) have been coming under heavy use, with loss of social, ecological and economic value. The problems are so serious that we are often forced to talk about restoring these ecosystems, rather than managing them. Take, for example, the case of the Newfoundland cod, used by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA 2005a) to illustrate what a resource collapse may look like (Figure 1.2). Cod is not an isolated case. Myers and Worm (2003) have shown a worldwide decline in communities of large, predatory fish (but perhaps not as widely as reported; Hilborn 2006). This accelerating loss of populations and species adds up to a biodiversity decline that is thought to be resulting in declines, not just of sources of food, but of a range of ecosystem services (Worm et al. 2006).

Figure 1.2 Example of nonlinear change used by MA (2005a) shows the growth and eventual collapse of the Newfoundland cod fishery

The focus of the book is on coastal resources and their users. The major resource in question is fisheries, even though I deal with other resources (ecosystem services) as well. Of resource users, the major group worldwide is small-scale fishers. They are more numerous than large-scale fishers and other kinds of resource user. The numbers justify the focus. Globally, 158 million tonnes (mt) of fish were produced in 2012, 11.6 mt from inland fisheries, 79.7 mt from marine capture fisheries, 41.9 mt from inland aquaculture and 24.7 mt from marine aquaculture. Of these, 136 mt were used for human consumption, and the rest for other purposes such as reduction to feed (FAO 2014). Small-scale fisheries account for some 90 percent of more than 120 million fisherfolk, people who depend directly on fisheries-related activities such as fishing, processing and trading (HLPE 2014). Hence, the issues of small-scale fisheries, such as the changing picture of coastal resource use and rapidly increasing aquaculture production, cannot be ignored.

This book is uniquely designed to address some of these issues by contributing to the development of a new interdisciplinary science of coastal and marine resource management. To accomplish this, I develop four strategies.

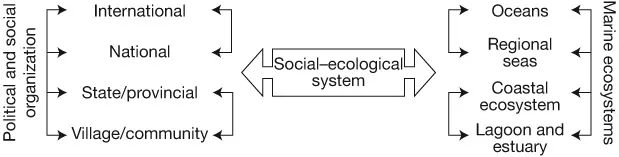

Figure 1.3 Matching social and ecological scales

The first is the use of a systems approach regarding interactions between human and environment systems, or social–ecological systems. The approach involves the consideration of social (human) and ecological (biophysical) subsystems together, rather than separately (Figure 1.3). The two subsystems are linked by mutual feedback and are considered to be interdependent and co-evolutionary (Berkes 2011). Second, I pay special attention to the human dimension of coastal and marine resource use. Most fisheries research focuses on fish rather than on fishers. This book dismantles the divide between natural sciences and social sciences and emphasizes the neglected human aspects of resource use, such as livelihoods.

Third, I emphasize community-based resource use, examining institutions and governance from the ground up. Small-scale fisheries and other resource use systems provide livelihoods and contribute to the food security of a far larger number of people worldwide than do industrial fisheries. Nevertheless, the discussion is relevant to all fisheries and some other resources. Fourth, I use an integrative approach to consider multiple theories to deal with the “big picture.” The book offers a synthesis, bringing together several approaches such as social–ecological systems thinking, resilience, commons, co-management, use of fisher knowledge, sustainable livelihoods and ecosystem-based management.

Rethinking Coastal and Marine Resources

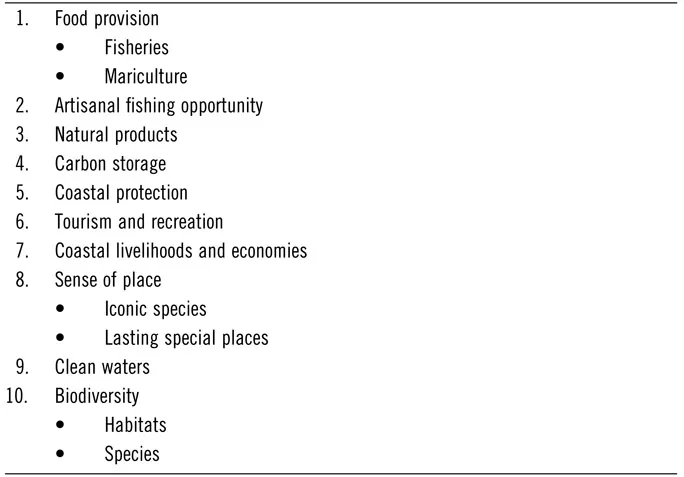

Resource management practices are constantly changing to deal with issues of sustainability and increased competition over coastal resources worldwide. Human impacts such as overfishing, habitat destruction, coral reef and mangrove losses, and pollution have damaged many coastal ecosystems and eroded their capacity to provide ecosystem services. Yet oceans and coasts continue to support human needs physically (food), ecologically (biodiversity), economically (livelihoods) and culturally (sense of place). Fisheries and aquaculture continue to provide food, and coastal resources support economies based on tourism and recreation. Building on the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA 2005a), Halpern et al. (2012) recognized ten “public goals” or major coastal and marine uses (Table 1.1), and the list can be expanded.

Table 1.1 Ten “public goals” or coastal and marine uses, according to Halpern et al. (2012)

Coastal resource management has an unfinished agenda. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say, an ever-changing agenda. The setting and priorities for management are constantly evolving, addressed by a large number of books, reports and papers over the years. This book extends the debates initiated in several volumes, perhaps starting with the 1990 book by McGoodwin, Crisis in the World’s Fisheries, and the 1998 book edited by Pitcher and colleagues, Reinventing Fisheries Management. The McGoodwin book was important in making the point that the fishery problem was not merely a biological problem, but a social problem as well. The Pitcher book took the bold step of questioning the management status quo. Charles’s (2001) book, Sustainable Fishery Systems, charted one of the possible new directions: using systems approaches for sustainable fisheries. Managing Small-Scale Fisheries, by Berkes et al. (2001), argued for a broader, interdisciplinary view of management and attempted to provide new tools for managers of international coastal fisheries.

Coasts under Stress, by Ommer and team (2007), took a creative interdisciplinary approach to pursue parallels between coastal ecosystem health and coastal community health. Fish for Life, edited by Kooiman et al. (2005), brought together an international cast of writers addressing governance, as a broader setting for management. A Fishery Manager’s Guidebook, edited by Cochrane and Garcia (2009), was prepared as a sourcebook, creating a new mix of interdisciplinary management practice, specifically targeting the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) community and international fishery resource managers. Both the Cochrane and Garcia (2009) book and the World Fisheries book edited by Ommer et al. (2011) explored the use of a social–ecological approach. The broader issues of coastal zone management were addressed by Cicin-Sain and Knecht (1998) in Integrated Coastal and Ocean Management. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment evaluated the coastal ecosystems of the world in relation to ecosystem services and human well-being (MA 2005a).

With a rich literature base of books, articles, other publications and web sites to draw from, the present volume is written with two goals in mind. The first is to contribute to the field of coastal and marine resource management and offer alternative approaches that emerge out of recent developments in interdisciplinary fields such as commons and resilience. Here, the audience comprises scholars, management professionals and practitioners. The second goal is to produce a book that can be used as a text in environment and resource management programs, toward a better-educated civil society. The dilemmas of coastal and marine resource management are part of a larger debate on environmental sustainability. They have counterparts in other resource areas, such as forestry and wildlife management, and other environmental fields, such as conserva tion, international development and environmental planning.

Changes in coastal and marine resource management can be seen in the context of larger, historical conceptual shifts that have been occurring in ecology and resource management. Various fields of applied ecology seem to be in the midst of three paradigm changes: (1) a conceptual shift from reductionism to a systems view of the world; (2) a paradigm change in the way shared resources or commons are theorized and managed; and (3) a shift from expert-based, technical management, to a broader, participatory governance. These changes are not specific to coastal manage ment but to environmental management in general. They provide the context and benchmarks in many areas of applied ecology, as they begin to incorporate human dimensions explicitly. Resource management is coming under critical inquiry, at a time when the science of ecology itself is undergoing major change. These ideas are explained further in the following three sections and developed in detail in Chapter 2, becoming cross-cutting themes for the rest of the book.

Paradigm Change from Reductionism to a Systems View

The environmental philosopher J. Baird Callicott (2003, p. 239) observed that, “for nearly half a century now, ecology has been shifting away from a ‘balance-of-nature’ to a ‘flux-of-nature’ paradigm.” In Callicott’s view, by the mid 1970s, the latter had begun to eclipse the former, and, by the 2000s, the shift was largely complete. It was a deep-seated change: from a conception of nature in a state of equilibrium, undisturbed by humans, to one in which nature is constantly changing and disturbed by many natural (and human) factors, a view of ecosystems as complex adaptive systems (Holling 1973; Chapin et al. 2009). It also made for a far messier kind of ecology: ecosystems as open, ill-bounded, disturbance-ridden systems, hardly stable.

Instead of possessing one equilibrium, ecosystems may temporarily settle into a domain of ecological attraction (or state) and may flip into other domains through various kinds of disturbance (Holling 2001; Levin 1999). These flips, however, are not at random; ecosystems respond to thresholds or tipping points (Walker and Meyers 2004). Some ecologists have been developing the idea that ecosystems are actually or potentially multi-equilibrium systems in which alternative states may exist over time, and that an ecosystem may flip from one state to another in some general, predictable ways, except that these regime shifts are not exactly predictable in space and time (Scheffer and Carpenter 2003).

There are some serious implications of this kind of thinking, and of the messier kind of new ecology. We can never possess more than an approximate knowledge of an ecosystem, and our ability to predict the behavior of multi-equilibrium complex systems, such as coastal ecosystems, is limited. Hence, models based on equilibrium thinking often do not work, not only because we lack data, but also because ecosystems are intrinsically and fundamentally unpredictable, and would continue to be so even if a great deal more data were available.

Recent practice in fisheries reflects the growing importance of recognizing complex adaptive systems thinking and the necessity of moving away from single-species stock assessment models to protecting the productive potential and resilience of the ecosystem as a whole (Holling and Meffe 1996; Cochrane and Garcia 2009). Once we put aside the idea of controlling nature, then we can then come to terms with the idea of dealing with resources through a learning-by-doing approach or adaptive management (Holling 1978). Adaptive management is the contemporary, scientific version of the age-old trial-and-error learning and knowledge production of traditional societies (Berkes et al. 2000). It starts with the assumption of incomplete information, and relies on repeated feedback learning in which policies are treated as experiments from which to learn.

One way to deal with uncertainty and complexity is to build local institutions that can learn from crises, respond to change, nurture ecological memory, monitor the environment, self-organize and manage conflicts. A complementary approach is to build working partnerships between man agers and resource users. The use of imperfect information for manage ment necessitates a close co-operation and risk sharing between managers and fishers. Such a process requires collaboration, transparency and accountability, so that a learning environment can be created and man age ment practice builds on experience. Focus on institutions, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction: The Ongoing Agenda

- 2 Natural Resources and Management: Emerging Views

- 3 Social–Ecological Systems

- 4 Resilience: Health of Social–Ecological Systems

- 5 Can Commons Be Managed?

- 6 Co-management: Searching for Multilevel Solutions

- 7 Coastal Zone: Reconciling Multiple Uses

- 8 Conserving Biodiversity: MPAs and Stewardship

- 9 Coastal Livelihoods: Resources and Development

- 10 Local and Traditional Knowledge: Bridging with Science

- 11 Social–Ecological System-based Management

- 12 An Interdisciplinary Science for the Coast

- References

- Appendix: Web Links and Teaching Tips

- Index