![]()

Section 1

Narrative Writing Strategies Aligned with the Common Core State Standards for Grades 3–8

![]()

1

Engaging and Orienting the Reader

What Does “Engaging and Orienting the Reader” Mean?

A strong piece of narrative writing begins by engaging the reader in the story and orienting them with key information about the characters, setting, and situation. The Common Core State Writing Standards highlight the importance of this concept, as Standards W.3.3.A, W.4.3.A, W.5.3.A, W.6.3.A, W.7.3.A, and W.8.3.A emphasize the significance of effectively engaging and orienting readers of narratives. In this chapter, we’ll discuss the following: what “engaging and orienting the reader” means; why this concept is important for effective narrative writing; a description of a lesson on this concept; and key recommendations for helping your students engage and orient readers of their own narrative writings. Along the way, we’ll examine how published authors engage and orient readers to their narratives, and explore what makes those authors’ works especially effective.

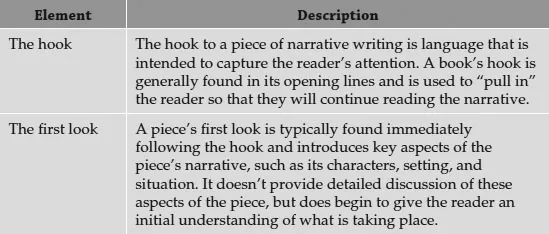

We’ll begin by considering what it means to engage and orient readers to a piece of narrative writing. The first of these components—engaging the reader—captures the reader’s interest and encourages them to want to continue with the piece. The second—orienting the reader—begins to introduce important information about the narrative, such as who the main characters are, where the story takes place, and what is taking place. Language that engages and orients readers provides two significant elements of narrative writing: the hook and the first look. Table 1.1 describes each of these elements.

Table 1.1 Key Elements of Engaging and Orienting Readers

Now, let’s examine how author Kate DiCamillo engages and orients her readers by providing a hook and first look at the beginning of her novel The Tale of Despereaux:

This story begins within the walls of a castle, with the birth of a mouse. A small mouse. The last mouse born to his parents and the only one of his litter to be born alive.

“Where are my babies?” said the exhausted mother when the ordeal was through. “Show to me my babies.”

The father mouse held the one small mouse up high.

“There is only this one,” he said. “The others are dead.”

(DiCamillo, 2003: p. 11)

In this passage, DiCamillo engages, or hooks, her readers with three opening sentences: “This story begins within the walls of a castle, with the birth of a mouse. A small mouse. The last mouse born to his parents and the only one of his litter to be born alive.” These sentences grab the reader’s attention with a few introductory statements about a mouse. Readers who encounter these opening points may keep reading to learn about the importance of this mouse, and why he is the only one of his litter to live. After these opening lines, DiCamillo orients the reader to some of the characters in the text by providing a first look at a conversation between a mother and father mouse. By incorporating this conversation, DiCamillo helps readers begin to develop an initial understanding of what is taking place. In this chapter’s next section, we’ll examine how the strategies of engaging and orienting the reader are especially important to effective narrative writing.

Why Engaging and Orienting the Reader Is Important to Effective Narrative Writing

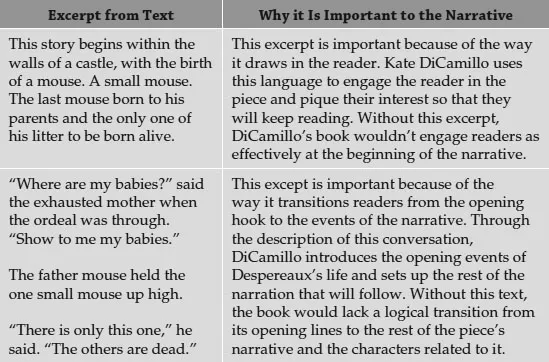

The writing tools of engaging and orienting the reader are integral to the success of a piece of narrative writing. If authors did not employ these strategies, it would be much more difficult for readers to engage with and understand their works. For example, if Kate DiCamillo did not engage and orient us readers at the beginning of The Tale of Despereaux, we would struggle with the opening of the book because there wouldn’t be anything in the text that draws us in, or introduces us to key aspects of the situation. While it’s possible that some readers would eventually figure out what is taking place, it’s also very likely that many readers would grow confused and frustrated by the fact that the author did not engage and orient readers, and would therefore stop reading. Table 1.2 explains why the language in The Tale of Despereaux that engages and orients readers is especially important to the piece.

Table 1.2 Importance of Language that Engages and Orients Readers in The Tale of Despereaux

As this table describes, these opening passages are essential to the reader’s engagement in and understanding of The Tale of Despereaux: they reveal Kate DiCamillo’s ability to grab the attention of her readers and orient them to key elements of a narrative. To further illustrate the importance of the narrative-writing tools of engaging and orienting readers, let’s explore how Lemony Snicket uses these strategies in the opening of The Bad Beginning (the first book in his A Series of Unfortunate Events sequence). First, let’s take a look at the opening text of this book:

If you are interested in stories with happy endings, you would be better off reading some other book. In this book, not only is there no happy ending, there is no happy beginning and very few happy things happen in the middle. This is because not very many happy things happened in the lives of the three Baudelaire youngsters. Violet, Klaus, and Sunny Baudelaire were intelligent children, and they were charming, and resourceful, and had pleasant facial features, but they were extremely unlucky, and most everything that happened to them was rife with misfortunate, misery, and despair.

(Snicket, 1999: p.1)

Lemony Snicket uses the first two sentences of this opening passage to hook the reader, as statements such as “If you are interested in stories with happy endings, you would be better off reading some other book” can intrigue potential readers, and encourage them to continue with the book. After these surprising and engaging first lines, Snicket begins to introduce the book’s characters and the challenges they face. Language such as “they were extremely unlucky, and most everything that happened to them was rife with misfortunate, misery, and despair” gives readers an opening look at the book’s events.

This excerpt from The Bad Beginning is a great example of the importance of engaging and orienting readers to effective narrative writing; without the text that hooks readers, and without the information that gives them a first look at the Baudelaire orphans’ situation, readers’ experiences with The Bad Beginning would vary significantly from their current ones. As this book is currently constructed, Lemony Snicket prepares his readers for the story he will tell in The Bad Beginning, by capturing their attention and providing information about the forthcoming challenges they will face (using an amusing and irreverent tone to do so). Without the language that performs these functions, readers would not be introduced to the book’s characters and events in the effective way that they currently are. In the next section, we’ll take a look inside a third-grade classroom and examine how the students in that class consider the importance of this writing strategy.

A Classroom Snapshot

“Since we’ve been talking about how authors engage and orient readers,” I tell my third graders, “I’ve been thinking about this in everything I read. Yesterday, I was reading Charlotte’s Web to one of my children and I was so struck by the way the author engages and orients readers that I wanted to bring it in to share it with all of you.”

The students smile, interested to see how the author of Charlotte’s Web, E.B. White, utilizes this strategy. These students and I have spent the past few classes discussing the narrative-writing strategy of engaging and orienting readers. On our first day working on this concept, I introduced this strategy to the students, explaining that when narrative writers engage and orient their readers, they provide a hook designed to interest readers in the story, and then a first look meant to introduce readers to some aspect of the piece. Next, we spent two class periods discussing why this strategy is important to effective narrative writing; we looked at the examples from The Tale of Despereaux and The Bad Beginning, discussed in this chapter, examined how those passages engage and orient writers, and talked about why doing so is important to those narratives. Today, I’m going to give the students more responsibility for their learning through the use of an interactive lesson: after the students and I discuss the language in Charlotte’s Web that engages and orients readers, I’ll divide them into groups, and ask each group to work together to do the same kind of identification and analysis with published texts they choose.

“Let’s take a look at the opening of Charlotte’s Web,” I tell the students, placing the book on the document camera and projecting the following text to the rest of the room:

“Where’s Papa going with that ax?” said Fern to her mother as they were setting the table for breakfast.

“Out to the hoghouse,” replied Mrs. Arable. “Some pigs were born last night.”

“I don’t see why he needs an ax,” continued Fern, who was only eight.

“Well,” said her mother, “one of the pigs is a runt. It’s very small and weak, and it will never amount to anything. So your father has decided to do away with it.”

(White, 1952, p. 1)

I read the text out loud as the students follow along and then ask, “What parts of this passage do you think the author is using to try to engage readers?”

Thrilled to see a number of student hands fly up around the room, I call on a young lady who answers, “The question in the first sentence. I think that’s supposed to engage us.”

“Well said,” I reply. “Why do you all think that the question in the first sentence is meant to engage readers?”

“Because,” responds another student, “it makes you wonder what the answer to the question is.”

“Nicely put,” I tell the student. “Putting a question at the beginning of a narrative, like E.B. White does here in Charlotte’s Web, is a great way to get a reader’s attention because, as you said, readers will wonder what the answer is to that question, which gets them engaged in the piece.

“So,” I continue, addressing the whole class, “if that part is meant to engage us, what language in this passage does E.B. White use to orient us to the situation in this narrative?”

“I think the rest of [the passage] does that, especially the parts about the pig,” states a student sitting in the front of the class.

“Why do you think that is?” I inquire. “Why do you thin...