![]()

1

Managers

Making a difference

This chapter covers:

- Motivation to manage, lead and learn – why you might accept the challenge of management

- Expectations placed on managers

- Getting the best learning – for yourself and for helping you to develop team members

You have already made a good start in the next stage of your development as a manager and leader by picking up this book. For some people that will be it and no progress will be made. For others they will read some of the contents, maybe even complete some of the suggested Activities and reflect on the Scenarios. Will you be someone who uses this book to add to a whole range of approaches that mean you continue your professional development as an early years manager? If the answer you give is ‘yes’ try this.

Activity 1.1 Motivation at work

What motivates you to do things within your professional work setting? Make a quick list.

Reflection

There are no ‘correct’ answers to this question but you may have identified motivators such as: professional pride; an internal desire to be the best you can be; or a feeling of making a difference to each child, perhaps fuelled by a feeling of righteous indignation focused on the life chances of different children. These would be internal motivators, things that are inside you and drive your behaviours. You may have identified external motivators such as: my manager expects this of me; regulators (like Ofsted) will ask to see evidence of my development; my team deserves a good (or great) manager; and team members need to know I am completing management development.

For most of us there are a mixture of motivators – and a good job too as these will help us to keep going when things get tough or priorities compete for our attention and energy.

Managers do things to make a difference

There is a wide range of ‘things’ that a manager in an early years setting does. This list includes tasks and activities under broad headings such as planning, organising and implementing practices that meet required learning and development, assessment, safeguarding and welfare, monitoring and reviewing practices, quality improvement, securing and allocation of financial and other resources, and many, many other things. It is no wonder that you are busy. This book has a specific focus on your role in relation to working with other people and teams to get all this done effectively and efficiently.

Some understanding of theoretical models can help you in understanding your own behaviours and provide you with options – and more importantly some ideas of how to develop and do things in a different way. Throughout this book there will be references made to models and theories with a brief overview or summary. If that is enough for you to apply to your practice, then that is great. Alternatively you may want to explore the ideas further and even get back to some of the original thinking that resulted in what have become well-known approaches. If so please follow the links and reference included, or embark on your own search. The latter will probably lead to you discovering fascinating and useful things, some of which you were not even looking for.

Motivation

You will have probably explored motivation theories within your practitioner training and education. A few useful theories have been summarised below.

Maslow

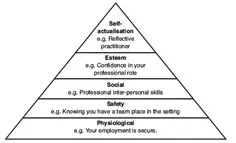

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Need (1943) is a great starting point and can be as applicable to managers and teams of practitioners as it is to parents and children.

Figure 1.1 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Need pyramid

The relevance of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Need for you as a manager and leader of people and teams can be summed up as the ability to focus on the task. Maslow demonstrated that, as individual people, and we would suggest as teams, we all get easily deflected from the work task if some of our basic needs are unmet.

It is useful to understand what motivates or demotivates people in your team. The best way of finding out is to ask them and then watch behaviours when you try to do more of what motivates and less of what demotivates. As with child development, observation is really important and a useful way of evaluating whether or not what people say motivates them does indeed have an impact on their behaviours. For example many people will say that what they get paid is a motivator – probably less so in our sector than in some other vocations and industries. However some research indicates that this is a reasonably short-term and low motivator.

Hertzberg

The work and studies of Frederick Hertzberg produced Motivation Hygiene Theory in 1959 (Kennedy, 1992) and identified two types of factors that impact on job satisfaction.

One type resulted in increased satisfaction among staff and these he called ‘motivators’. Examples included being recognised for doing a good job, appreciation, achievement of outcomes and being given responsibility.

The second type had little positive effect on satisfaction when they were present, but an absence caused dissatisfaction. Hertzberg called these the ‘hygiene’ factors and in a similar way that we assume environmental hygiene is good when there is an absence of illness, then as managers when the working environment is good there is an absence of dissatisfaction. Examples include the physical working conditions – heat, light, noise levels – and policies, procedures and practices.

Seldom will a member of your team overtly thank you for writing such clear policy and procedure statements, or appreciate you for the way you allocate rotas and tasks. However when policies are unclear, confusing or absent when needed, or when there is a dispute over the fairness of tasks and rotas, staff will notice and probably let you know and it will distract them to some extent from their primary task at work.

Activity 1.2 Positively positive

To make a positive difference as a manager you need to find ways of providing ‘job enrichment’. Make a list of ways this is currently done in your work setting.

What other ways can you think of adding to this list?

Reflection

Did you find it easy or difficult to list ‘job enrichment’ approaches currently used? Maybe your list is worth sharing with some colleagues to consider what that tells you about opportunities to maintain or develop a motivational working culture. Are there opportunities to provide risk assessment challenges to teams and people at work? How good and consistent is your work setting at ‘catching people getting things right’, acknowledging this and even celebrating good things? If you are good at these things, can you think of ways to further expand or develop this to keep things fresh and interesting for longer-serving team members?

Great expectation

It often feels like however well you do, however much you do, there is more expected of you – as a manager, as a practitioner and as a professional carer. Consider for a moment who or what sets these expectations?

Probably we can all think of a significant person in our lives who has expected the best from us. From our personal life a teacher or our own parent; from our professional life a colleague, manager or one of the children’s parents; or perhaps a regulatory body that sets a standard, evaluates the impact of our efforts and reports on us, such as Ofsted, Social Services or Investors in People. Perhaps we expect more of ourselves, to be the best we can be or better than we previously were.

While it is probably true that you can’t meet every expectation all the time, as a manager you need to consider which expectations are the highest priorities. Once you identify these, you can be clear what the expectations actually are and how what you do is evaluated against these.

For external regulatory bodies this is usually reasonably straightforward as they publish standards, criteria and evaluation or assessment processes. Ofsted has clearly set out standards and expectations that inspectors use, specifically related to management and leadership. Your challenge is to become familiar with these, relate them to your work setting and your practices and to be able to provide evidence to meet the expectations set. Your work on self-assessment will help this process, as will your early years practice of reflection.

For individuals, such as team members or sometimes your manager, this process can be more difficult. In the case of your manager, there should be a formal appraisal process with reference to your job description and agreed objectives. These can inform what the expectations are and provide a framework to evaluate how well you have met them. For team members this is probably less defined and open to subjective interpretation, however it can still be addressed through establishing effective two-way supervision discussions that provide an opportunity for you to hear their views and experiences of what it is like to be managed by you.

All these expectations and ways of evaluating your performance against them can be used to help you continue to do things that work and identify things that you might change in your management approaches. However remember that you cannot meet everyone’s expectations all the time and you will need to make decisions that are the most appropriate and important for the children, the service and organisation’s purpose.

Learning theory

Take a moment to think about some effective ways that people, including you, learn. This will help you to get the most from this book. It will also be applicable to your management practice.

Have you ever wondered why, when you are presenting some new ideas to staff it sometimes seems ages until they, individually or collectively, seem to understand it and implement changes?

One reason why others take some time in learning something that you are presenting is that the first time you share the information is their first time of hearing or reading or seeing it. For you it will be the next time as you will have probably thought about it, researched it, challenged its application to your situation and rehearsed how you will share it with your team. Therefore you will have gone through some form of learning cycle to arrive at the place when you are feeling confident enough ...