![]()

p.1

Chapter 1

Action

| Angie: | “What do you feel like doing tonight?” |

| Marty: | “I don’t know, Ange. What do you feel like doing?” |

| Angie: | “We’re back to that, huh? I say to you, ‘What do you feel like doing tonight?’ And you say back to me, ‘I dunno. What do you feel like doing tonight?’ Then we wind up sitting around your house with a couple of cans of beer watching the Hit Parade on television.” |

(from the 1955 movie Marty, written by Paddy Cheyefsky)

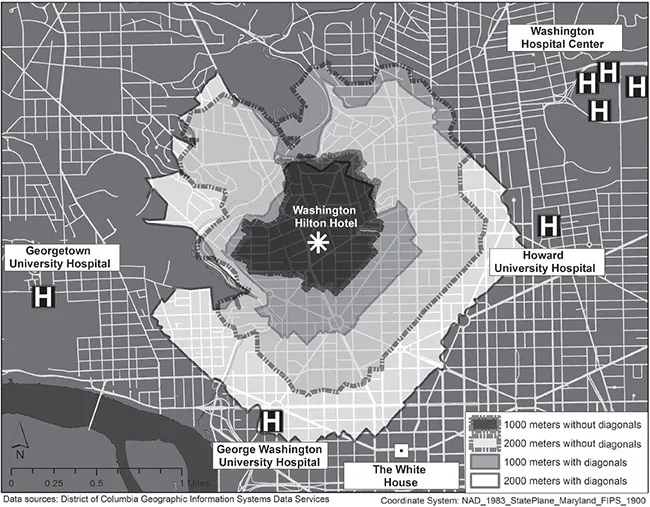

The Washington Hilton Hotel is known to veteran transportation professionals as the one-time home1 of the annual meeting of the Transportation Research Board. The meeting is the world’s largest gathering on transportation issues, attracting more than 10,000 participants every January. Though unmarked by a plaque, the hotel is also the site where, on March 30, 1981, John Hinckley shot President Ronald Reagan, White House Press Secretary James Brady, Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy, and District of Columbia police officer Thomas Delahanty. Within moments, Secret Service bodyguards had hustled Reagan—still unaware that he had been hit—into a limousine and were speeding away from the scene and toward the White House, following Secret Service protocol. But the discovery that Reagan had been injured by a bullet and not, as he initially believed, by the force of being pushed into the limousine, forced Secret Service agent Jerry Parr to immediately order the car re-routed to George Washington University Hospital, the closest hospital to the scene of the shooting.2

With the life of the President of the United States hanging in balance, Jerry Parr had to quickly choose between several nearby hospitals. The President is usually treated at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, northwest of the Hilton; this location was relatively far away. Another hospital roughly the same distance from the Hilton but due east was Howard University Hospital (Figure 1.1), and a little farther east of that were the Washington Hospital Center, the Veterans’ Hospital, and Children’s Hospital, which are clustered together; in the opposite direction (roughly due west from the Hilton) sits Georgetown University Hospital. Routing Reagan to George Washington University Hospital was the best decision given the local geography, the time urgency, and the fact that the car had started out southbound toward the White House.

p.2

Several opportunities (referred to in this book as chances) were quickly evaluated by Jerry Parr: George Washington University Hospital, Bethesda Naval, Georgetown University Hospital, Howard University Hospital, Washington Hospital Center. All of these are highly regarded hospitals, though with different specialties. The quality of care at several of these hospitals would probably have been sufficient to save the President’s life.

One constraint in this particular scenario was time: the President was actively bleeding. Agent Parr was obliged to minimize travel time, subject to another constraint that the quality of care at the chosen destination would be sufficient. The travel time depended on several factors.

There was other traffic on the road, and unlike a normal presidential excursion, the trip lacked a prepared route or advance escort service to clear the way. The road network itself was a constraint, as the presidential limousine could only drive on existing streets, with buildings, Washington’s famous traffic circles, and other objects posed as barriers.3

Other vehicles on the road were clearly competitors in this life-or-death journey. Once at the hospital, other competitors appeared in the form of patients who placed their own demands on the doctors Reagan needed (in this particular case, however, the doctors had been in the hospital at a meeting, and so were readily available).

The mere existence of a road between the hotel and the hospital, of the hospital itself, and of a staff of skilled physicians all depended on the presence of a city full of people who would use those facilities on a daily basis, making them available when needed by the President. These factors acted as complementors. The availability of alternative routes and alternative hospitals is testament to the large number of complementors that could be drawn on. The hospital would not exist but for George Washington University, which though a private university, grew out of a Congressional charter signed by President James Monroe for “The Columbian College.”4

p.3

Predicting Decisions

Understanding why and how people make the transport decisions they do—to get around town and conduct their daily lives—is a messy business. There are countless informants; the degree to which informants are guided by predictable or rational processes is questionable. Why and how public officials in cities make collective decisions about transport–land use matters is even messier. Failing to consider factors for what motivates all sorts of decision-making, we are failing to understand key foundations and how to best address them. As Honest Abe (President Abraham Lincoln) asserted in 1858, “if we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do, and how to do it.”5 If only it were that easy.

Transport and land use systems are multi-layered and complicated. There are many actors who execute different decisions over different time horizons. In this book, we focus on three actors: individuals, developers, and governments. The first part of the book takes on the decisions of individuals and this first chapter explains different ways of understanding that decision-making.

The behavioral and social sciences are long on theories to model and predict human decision-making. The goal of almost all theory is to help explain some outcome (behavior) as a function of some inputs (variables), positing some relationship between them. Some theories are relatively abstract, while others are more applied; some theories are empirically tested, while others are more qualitative. Depending on the context, some hold up pretty well in explaining what they are supposed to explain. However, all have more than a healthy dose of error—an often unaccounted for dimension—and the manner in which this error is incorporated into the prediction process helps set apart the theory most often relied on in travel demand forecasting work.

Imagine that you are presented with a challenge of guessing which of two objects is heavier. Sometimes you will be right, sometimes wrong. The likelihood of being right depends on the difference in their weights as well as your knowledge or skill. In 1929, Louis Leon Thurstone proposed a “Law of Comparative Judgment,” which, greatly simplified, says that perceived weight is w = v + e, where v is the true weight and e is a random error with an average value of zero.6,7 The finding from this experiment is that the greater the difference in weight, the greater the probability of choosing correctly. This experiment is analogous to predicting decisions, such as which mode of travel individuals decide to use. Adapting this approach to study how people make choices, economists have developed a method for explicitly accounting for the actual choice as well as the error term. They do so wrestling with a concept likely familiar to emerging transportationists known as utility (where the observed utility = predicted utility + random term).

p.4

Economists developed the concept of utility based on the general proposition that “people make decisions to advance their self-interest.”8 People prefer alternatives with the higher utility—an unobservable characteristic assessed by examining choices. One of the conditions of utility theory is non-satiation: more is preferred to less of any normal good (and if less is preferred to more, we just define the “good” to be less of something). However, utility theory does not assume that two of something is necessarily twice as good as one of something; it allows for diminishing (or increasing) returns. According to utility theory, the demand for different goods takes into account the prices of all goods, income, and tastes and is subject to budget constraints. In a similar manner to elementary consumer economic theory, consumers take advantage of a good when the utility of consuming the good is higher than the disutility of its cost (including the opportunity cost of forgoing alternatives). The demand for different goods or services (defined as everything from a community, a car, or a cell phone) depends on prices of all goods, household income, and personal tastes.

Travel behavior theory differs from consumer choice theory in that transport choices tend to be discrete (e.g. where to go, when to go, how to go) rather than continuous (e.g. how much to buy).9 The reasons may be continuous. The driver may choose the mode of car because it is safer or cheaper than taking the bus—both safety and cost are continuous variables. However, driving a car is distinct from riding a bus operating on a fixed route; the choices are qualitatively different, a bus is not just a bigger car.

Similarly, the demand for a transit trip may be viewed as a function of both the benefits of the trip and its costs: time (access and egress time, wait time, in-vehicle travel time), money (transit fare and cost of parking at a park and ride in some cases), and uncertainty (schedule adherence, safety, delays). This thought process allows us to identify a basic demand function that incorporates the relationship between the cost (or price) of a good and the level of demand. As long as the cost of consuming a good is lower than an individual’s willingness to pay, the good is consumed (or a mode of travel is chosen).

Mode choice models thus have roots in Thurstone’s psychological theory and in Kelvin Lancaster’s consumer behavior theory,10 as well as in modern statistical methods. Stanley Warner first applied concepts of utility theory to disaggregate travel in 1962. Using data from the Chicago Area Transportation Study (CATS), he investigated classification techniques using models from biology and psychology. Building on the work of Warner ...