- 456 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Practical Guide to Evidence

About this book

Practical Guide to Evidence provides a clear and readable account of the law of evidence, acknowledging the importance of arguments about facts and principles as well as rules.

This fifth edition has been revised and updated to address recent changes in the law and debates on controversial topics such as surveillance and human rights. Coverage of expert evidence has also been expanded to include forensic evidence, bringing the text right up-to-date.

Including enhanced pedagogical support such as chapter summaries, further reading advice and self-test exercises, this leading textbook can be used on both undergraduate and professional courses.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

Summary

Introduction

Evidence and proof

Defining ‘evidence’

Relevance, weight and admissibility

Terminology

Three important characteristics of the law of evidence

The function of the judge and jury

The European Convention on Human Rights

Introduction

Law cannot be properly understood without some knowledge of the context in which it operates. Just as the student of commercial law needs to understand something of what is involved in ordinary commercial transactions, so the student of the law of evidence requires some understanding of what is involved in the trial process and the ways in which evidence can be ‘put to proof’. This chapter begins by outlining the concept of ‘proof’ and then goes on to discuss the definition of what will or will not amount to ‘evidence’. An outline is then made providing a short glossary of some of the technical terms that are commonly encountered when studying the law of evidence. The chapter continues with a consideration of the concepts of relevance, weight and admissibility. These are fundamental to the consideration of all aspects of the law of evidence. Discussion is then given as to the main characteristics of the law of evidence, the role of the judge and jury during a trial and the effect/influence of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Evidence and Proof

A useful way of approaching this topic is by the consideration of a case which was notorious at the beginning of the 20th century and which is still often referred to today. In this case the defendant was a Dr Crippen who was charged in 1910 with the murder of his wife. According to the prosecution, Crippen had fallen in love with his young secretary, Ethel Le Neve, and had decided to kill his wife to leave himself free to marry Ethel. It was alleged that one night he put poison into a glass of stout, his wife’s regular nightcap. The poison might have been sufficient to kill her, or it might merely have made her unconscious. His wife did die and it was alleged that he drained the blood from her body, dissected it, and separated the flesh from the bones. He then buried the pieces of flesh in the cellar of the house where they lived. The bones and the head of the corpse were never found and it was assumed that they had been burned. To explain his wife’s absence Crippen at first told her friends that she was staying with her sister in America and later he said that she had died there. When the police began to make enquiries, he told them that his wife had left him and that he had been too embarrassed to tell the truth to friends and neighbours. Crippen had not yet been arrested, and shortly after his interview with the police he hurriedly left the country with Ethel Le Neve. Meanwhile, the police dug up the cellar floor of his home and discovered human remains buried there. Crippen was then followed and brought back to England to stand trial.

Imagine yourself now in the position of a lawyer for the prosecution in this case. You know, of course, what constitutes murder in English law but, given these facts and the law, what do you think the prosecution would have to establish before a jury would be likely to find Crippen guilty of murder? The first thing that had to be proved was that Mrs Crippen was actually dead. Crippen maintained when questioned by the police and later at his trial that his wife had left him and that he knew nothing of the remains in the cellar. This meant that it was necessary for the prosecution to establish that the remains were those of Mrs Crippen. The prosecution also had to show that it was her husband who had killed her and that he had done so intentionally. This meant that they had to prove that Mrs Crippen had died from poisoning and that the poison had been administered by her husband with the intention of causing her death.

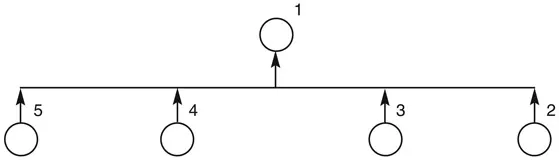

The task faced by the prosecution is illustrated by Figure 1.1. Item 1 represents ‘the thing that has ultimately to be proved’. This expression can be shortened by adopting a term used by JH Wigmore:1 the ‘ultimate probandum’. In this case, it is expressed by the proposition ‘Crippen murdered his wife’. Numbers 2 to 5 inclusive represent what Wigmore called penultimate probanda.2 These are the propositions which, taken together, go to prove the ultimate probandum. Unless there was some evidence to support each one of the penultimate probanda, a defence submission that there was no case to answer would have been likely to succeed.

Figure 1.1

Key list

- Dr Crippen murdered his wife (ultimate probandum)

- Mrs Crippen was dead

- She had died as a result of being poisoned

- Dr Crippen had administered the poison

- He had done so with the intention of causing her death

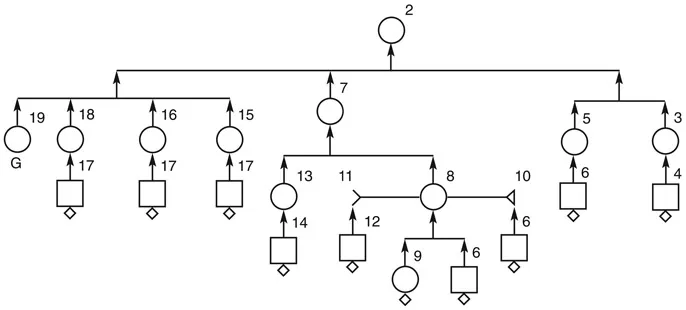

It is not necessary, for the purpose of understanding the process behind proving a case, to show how all of the penultimate probanda were proved in the Crippen case. It is enough to concentrate on the first of these, the fact that Mrs Crippen was dead (noted at number 2 in Figure 1.1). The elements of proof required here are illustrated in Figure 1.2.

The following points should be noted:

- (a) proof is met by establishing several sets of inferences which ultimately go to prove the fact that Mrs Crippen was dead;

- (b) each set of inferences rests on a foundation, which is marked in Figure 1.2 either by a diamond shape or by the letter ‘G’;

- (c) there are three types of foundation on which sets of inferences may be based:

- ■ the testimony of a witness at trial, represented by a square with a diamond beneath it. Examples are the testimony of the forensic scientists on either side of the case (numbers 6 and 12);

- ■ an item of ‘real evidence’, ie, something which the jurors can examine for themselves. An example of this would be a piece of flesh collected from the cellar and said by the prosecution to bear an identifying scar. This type of ‘foundation’ is represented by a circle with a diamond beneath it (number 9);

Figure 1.2Key list

Figure 1.2Key list- 2 Mrs Crippen was dead

- 3 Some remains were found in the cellar

- 4 Police testimony to this effect

- 5 The remains came from a human body

- 6 Prosecution expert testimony to this effect

- 7 The body was that of Mrs Crippen

- 8 A piece of the abdomen bore the mark of an operation scar

- 9 Item of real evidence

- 10 The shape of the mark was more consistent with a scar than with a fold

- 11 The mark may have been caused by folding

- 12 Defence expert testimony to this effect

- 13 Mrs Crippen had an operation scar on her abdomen

- 14 Her sister gave testimony to this effect

- 15 Mrs Crippen had not been seen since 31 January 1910

- 16 Mrs Crippen had friends and relations

- 17 Prosecution testimony to this effect

- 18 Mrs Crippen had a friendly, outgoing personality

- 19 Someone with such a personality who has not communicated with any friends or relations for some months may be dead

- ■ a generalisation about the way things are in the world, for example, number 19, represented by a circle with the letter ‘G’ beneath it;

- (d) all three types of foundation have in common the fact that the members of the jury rely on their own perception in order to analyse them. The jurors can see and hear the witnesses giving oral evidence in the witness box. They are able to see the items of real evidence. They rely on their own previous perceptions and their experience, in order to decide whether or not to accept the truth of a proposed generalisation. If they recognise the statement as being something that is either already part of the way in which they understand the world, or as something that at least fits with their understanding, they are likely to accept it; otherwise, it is likely to be rejected. In this way, members of the jury have a direct understanding of all foundational items. Any item that is not foundational has to be inferred, and every process of inference is open to error and so apt to produce a false conclusion. The majority of the things listed in Figure 1.2 are, like the majority of items of evidence in any case, non-foundational and therefore to be regarded with particular care before their truth is accepted. Direct perceptions are open to error, of course, but inferences relating to events that occurred in the past provide additional scope for error;

- (e) just as a set of inferences is based on a foundation, so each inference in the set is based on those immediately following it. This relationship is hard to define, but for these purposes it will be enough to say that a basing item, often taken in conjunction with other items of evidence, makes another item in the chain of proof to some degree likely. For example: it may be thought that once it is established that a piece of the abdomen bore the mark of an operation scar (number 8) and that Mrs Crippen had an operation scar on her abdomen (number 13), it is likely that the remains were those of Mrs Crippen (number 7). Whether a jury member is convinced by any particular inference will depend on how cautious they are in forming beliefs and what weight they think ought to be attached to the data on which the inference in question is based. Where the prosecution or defence set out to prove something they will ideally be able to rely on an accumulation of different forms of evidence from different witnesses. So, for example, if numbers 15 to 19 (relating to Mrs Crippen’s disappearance) stood alone, a jury may be willing to accept that Mrs Crippen’s death was no more than a remote possibility, but the likelihood that she is dead becomes much stronger when evidence of the discovery in the cellar is added. ‘Likelihood’ in this context is often referred to as ‘probability’, meaning probability of any degree, however slight;

- (f) the significance of a piece of evidence lies in the fact that it makes a particular inference either more or less likely to be true. Note the inference represented by number 8 in Figure 1.2. The prosecution needed to show that the remains found in the cellar were those of Mrs Crippen. The prosecution hoped to establish this by proving that Mrs Crippen had an operation scar on her abdomen and that an identical scar was found on one of the pieces of flesh discovered by the police. The defence countered this argument by calling expert evidence to the effect that the mark on the flesh was not a scar, but a fold that had developed after burial. Numbers 10 and 11 represent the expert evidence relating to this issue. Whether the jury accepted the truth of the inference represented by number 8 would depend on which expert they found the more persuasive.

Wigmore’s chart system is a way of methodically considering the facts of any case. An advocate must ensure that they correlate all available evidence in order to support their client’s case. They must also ensure that they are aware of the weaknesses in their own case and in that of their opponent.

Defining ‘Evidence’

Wigmore thought it ‘of little practical consequence to construct a formula defining what is to be understood by the term “evidence”’, and he may well have had a point. He nevertheless attempted to define the concept of ‘evidence’3 and authors of textbooks on evidence have traditionally also set out to provide a definition. The most satisfactory attempt of its time was that made in the 19th century by WM Best, who, influenced by Jeremy Bentham, defined evidence as ‘any matter of fact, the effect, tendency, or design of which is to pr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface to the fifth edition

- Extract from preface to the first edition

- CONTENTS

- Table of cases

- Table of statutes

- Table of statutory instruments

- Table of European legislation

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Development and current objectives

- 3 Documentary and real evidence

- 4 Facts not requiring proof

- 5 Competence and compellability

- 6 The course of testimony

- 7 Burden and standard of proof and presumptions

- 8 The rule against hearsay

- 9 Hearsay exceptions

- 10 Hazardous evidence

- 11 Confessions and improperly obtained evidence

- 12 Character evidence

- 13 Opinion evidence

- 14 Judicial findings as evidence

- 15 Privilege and public interest immunity

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Practical Guide to Evidence by Christopher Allen,Chris Taylor,Janice Nairns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.