Margaret Lowenfeld

The early roots of Sandplay began with pediatrician, Margaret Lowenfeld, in early twentieth century London. Dr. Lowenfeld had suffered an unhappy, although financially privileged childhood, coming from an upper class family of both Polish and English heritage. Lowenfeld returned to Poland following the First World War and was profoundly moved by the trauma and suffering the children had experienced (Mitchell & Friedman, 1992). From that moment on she was determined to find a way to work with children that would allow her to understand their thinking processes. She also wanted a method that she could record for later study.

In the course of pondering how she might accomplish these goals, Lowenfeld happened to recall a book by well-known social critic and writer, H. G. Wells, called Floor Games (Turner, 2004). This delightful little book is Wells’ account of his young sons’ imaginative play on the nursery floor, which involved a variety of wooden blocks, miniature figures, and objects found around the house and garden. Through the course of each week, the boys built islands, cities, and countries, and had great fun playing with them. Lowenfeld thought that this might be a good approach to working with the children at the clinic, so she gathered small toys and miniature figures together in a large box, calling it the Wonder Box. Lowenfeld noticed that the children in the clinic took the figures from the Wonder Box and put them in the sand box to build their worlds. She thus made a small sand tray where the children would have a private place to build their worlds when working with the therapist. What the children did with the Wonder Box was inspired and this was the birth of Lowenfeld’s World Technique. It is not an exaggeration to say that it was the children who invented Sandplay (Lowenfeld, 1979).

Margaret Lowenfeld was a true pioneer in child psychotherapy who is not given much mention in the annals of psychology. A contemporary of Melanie Klein and Anna Freud, Lowenfeld was the first clinician to treat children through the medium of free play. She had a deep understanding of children and realized that attempting to help children by talking with them would not work. Lowenfeld sat with each child respectfully and asked them to “make a picture of your world” in the sand tray. She sketched the child’s creation and spoke with them about it. Her intention was to understand how children think.

Dora M. Kalff

Dora Kalff, the founder of what we now know as Sandplay, came from a prosperous family. Her father, August Gattiker was a highly respected Army Colonel and politician. He manufactured textiles and had a deep interest in religion. Dora Kalff had a rich education in the humanities. In 1923 she graduated from the prestigious Boarding School Hochalpines Institut Ftan, located in the beautiful Engadin region of the southern Alps. After this she attended Westfield College, London, where she studied philosophy. In Paris she studied piano with renowned pianist Robert Casadesus, receiving a Concert Certificate. Dora Kalff studied Greek, Sanskrit, and Chinese, and was fluent in German, Dutch, Italian, English, and French. It was during her Chinese studies that she discovered a great interest in Eastern religions.

In 1933, Dora Kalff married Dutch banker, Leopold Ernst August Kalff, and moved to Holland. She had two sons, Peter Bedouin and Martin Kalff. The late 1940s proved to be a difficult time for Kalff. The Nazis had invaded Holland and occupied her house. She returned to Switzerland and lived with her sons in a small mountain village called Parpan (Punnett, 2013). Also during this time, Kalff’s father died. Dora Kalff soon realized that she could not support herself and her children and would need to earn an income.

As it worked out, Gret Baumann, Carl and Emma Jung’s youngest daughter, took her holidays in Parpan (Punnett, 2013). Baumann recognized that her own children were always calm and happy when they returned from playing at Kalff’s house, so she decided she should meet this neighbor. Soon Kalff and Baumann became friends and Dora Kalff told her about her financial difficulty and her need to find a career. Baumann suggested that psychology might be good for her, as she was so good with children.

Baumann then introduced Kalff to her parents, Carl and Emma Jung. Kalff did her analysis with Emma Jung, and studied Jung’s psychology for many years, after which Carl Jung suggested that she develop a way to do Jungian analysis with children.

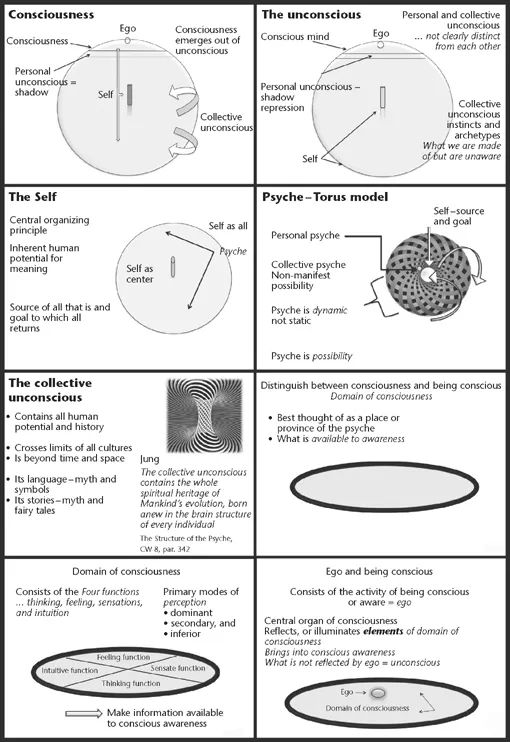

In the 1950s Kalff attended a presentation of Lowenfeld’s World Technique at a psychological congress in Zurich. Being familiar with Lowenfeld’s method, Carl Jung encouraged Kalff to go to London to study with her (Mitchell & Friedman, 1992). While in London, Kalff also studied with D. W. Winnicott and consulted with child analyst, Michael Fordham (Kalff, 1980/2003). As she witnessed the worlds that the children were making in Lowenfeld’s clinic, Kalff recognized what Jung called the process of individuation spontaneously occurring over the course of several worlds. Individuation is the psyche’s process of integrating new material from the unconscious with the conscious personality, for the purpose of self-discovery grounded in the wholeness, or the truth of oneself. As Lowenfeld traditionally discussed the sand worlds with the children, Kalff was greatly concerned that this would force too much conscious awareness on the tray’s content and would interfere with the individuation process. Kalff recognized that it was critical that the therapist not interpret the world, or sand tray construction with the client. Kalff knew that the therapist’s ability to understand and hold, to provide silent support, the client’s work provided the necessary safety the newly developing psychic material needed to come into its maturity. She did say that a verbal discussion of the work could be beneficial, after sufficient time has passed for it to integrate into consciousness (Kalff, 1991). In 1957, Kalff discussed her concerns with Lowenfeld and they agreed to have two separate methods. Lowenfeld’s would continue to be called the World Technique and Kalff’s would be known as Sandplay.

A great influence in Dora Kalff’s life and work was her meetings with several Eastern spiritual teachers (Kalff, 1980/2003). Among these included Daisetz Suzuki, Trichang Rinpoche, the teacher of the Dalai Lama, and the Dalai Lama. Kalff’s understanding of the depth and meaning inherent in all beings and events matured and flourished during this time. In the principles of the Eastern traditions, Kalff recognized what Carl Jung described psychologically as the rectification of the conscious mind, or ego, to the central truth of the personality, the Self. Although Kalff did her analysis with Emma Jung and studied at the Jung Institute of Zurich for six years, she was denied certification as a Jungian Analyst for not having a tradition university education (Mitchell & Friedman, 1994). This surprising rejection was a great disappointment, but Kalff, nonetheless, carried forward with her work. Both Emma and Carl Jung attempted to intervene on her behalf, but to no avail. Much later she was accepted as a full Analytic member of the Jung Institute for having made such a great contribution to the field.

In 1966, Dora Kalff wrote what we know in English as Sandplay: A Psychotherapeutic Approach to the Psyche (2003). Following her death in early 1990, Dora Kalff’s Sandplay method continues to grow. In addition, several clinicians have developed alternative ways of working therapeutically with the sand tray and miniature figures for a variety of purposes. We will explore some of these methods in this volume. Although Sandplay is not a panacea and is often used in conjunction with other treatments, particularly in cases of complex trauma, I can say unequivocally that Kalff’s Sandplay method is a very profound and far-reaching form of psychotherapy. We are indebted to this wise and courageous teacher for the gift that she continues to give to thousands of children and adults.