![]()

1

Introducing the Japanese economy

In the modern imperial period after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Japanese government attempted to develop the economy by promoting the national slogan of “rich nation, strong army”. It was the manifestation of economic nationalism in response to western imperialism. Japan began the process of industrialization with the government leadership in the Meiji era, but later private sectors acquired greater scope of business freedom. However, after Japan suffered from a severe economic depression in the late 1920s, the military government began to intervene in the economy in the early 1930s. Eventually, the Japanese economy was devastated during the Second World War. After Japan’s defeat, the United States, which led the Allied Powers, occupied Japan and postwar Japan began its economic reconstruction. The US occupation force implemented several reforms to demilitarize and democratize Japan, including the enactment of a new democratic constitution that proclaimed that sovereign power resides with the people and that renounced war as a sovereign right of the nation. However, its focus moved to the strengthening of Japan as a counter-communism force against a background of the intensification of the Cold War. After achieving independence in 1952, Japan under the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) attempted to remilitarize Japan by amending a new constitution in the 1950s. However, this aim did not materialize. Since then, Japan focused on economic growth and achieved its “economic miracle” in the 1960s. Despite a slowdown due to the oil crises, the Japanese economy continued to grow in the 1970s and had a frenzied period of growth in the bubble economy in the late 1980s. Since 1955, when the LDP was created, Japan maintained political stability under the political dominance of the LDP (called the “1955 system”) until 1993. This political stability provided a favourable condition for economic growth in postwar Japan.

This chapter will introduce the Japanese economy by beginning with an analysis of the major developments of Japanese capitalism in the prewar era. The chapter will examine government economic policy after the Meiji Restoration, Japan’s industrialization with zaibatsu economic conglomerates as an important economic actor, and the war-time planned economy of the 1930s until the end of the Second World War based on the extensive intervention in the economy by the military government. The chapter will then examine the formation of the postwar economy until the collapse of the bubble economy in the early 1990s. The chapter will periodize the postwar economy between 1945 and 1990 into: 1) economic reconstruction after Japan’s defeat in the Second World War (1945–late 1950s); 2) economic miracle in the 1960s; 3) lower economic growth in the 1970s as a result of the oil crises; and 4) trade conflict with the US and the bubble economy of the 1980s. The chapter will examine the impact of the US occupation policy and the “Yoshida doctrine” on the formation of the postwar economy in the first period and then the factors that contributed to Japan’s economic miracle in the 1960s from the perspective of state–market relations (e.g. government intervention in the economy with the industrial policy implemented by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) and business practices). The chapter will then discuss the economic slowdown of the 1970s despite the relatively good performance of the economy compared to western economies. The chapter will highlight that this led to western admiration of the Japanese economy, especially Japan’s industrial relations, and the emergence of the nationalistic nihonjinron (theory of Japanese-ness), which emphasized Japanese uniqueness and superiority. Finally, the chapter will discuss Japan’s trade imbalance with the United States and the economic bubble of the late 1980s.

PRE-SECOND WORLD WAR ECONOMY

Since the mid-seventeenth century, the ruling Bakufu (military government) of the Tokugawa dynasty in Japan had closed the country from the outside world to prevent the spread of Christian influence and to monopolize trade with foreign countries (Elisonas 1991). However, in 1854, Japan was finally forced to open-up the country by Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States, who visited Japan in formidable battleships and threatened the Bakufu with possible attack should they refuse to open the country. Japan was forced to conclude the Friendship Treaty with the US and opened the country. Similar treaties with Russia, Britain and the Netherlands were concluded soon later. After signing the Friendship Treaty, the US sought to enter into a commercial treaty with Japan and the US–Japan Commercial Treaty was concluded in 1858. It was an unfair treaty from the Japanese perspective in two respects: firstly, Japan did not have autonomy to decide its own tariff rates, and secondly, Japan was required to hire foreign judges when foreigners were indicted. Japan later concluded similar commercial treaties with Russia, Britain, France and the Netherlands.1

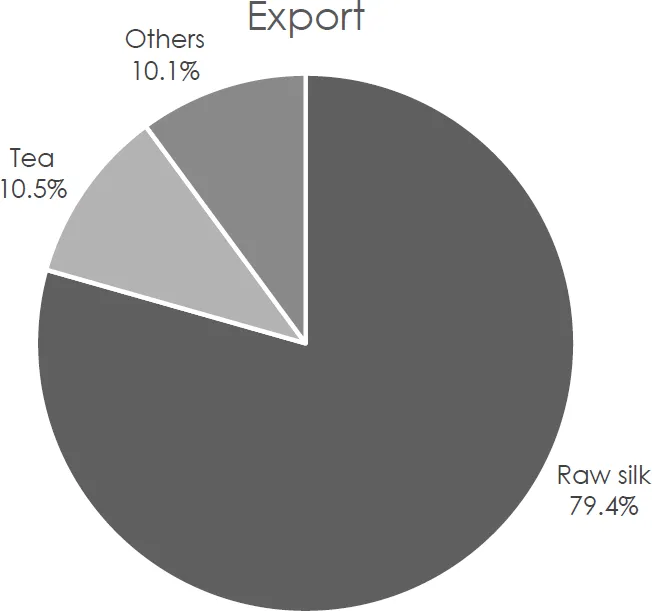

The opening of trade relationships had a great impact on the Japanese economy. Japan’s main export products included raw silk and tea and its main import products included woollen fabric, cotton cloth and military products (see Figure 1.1). While the growth of raw silk exports promoted the silk industry, the import of a large amount of cotton cloth negatively affected the domestic cotton textile industry (Beasley 1989: 306; Hane 1992: 69–70; Jansen 1989: 340). In addition, the difference in the ratios between gold and silver in Japan (1:5) and overseas (1:15) enabled foreign merchants to purchase gold much more cheaply in Japan and sell it more expensively outside Japan. As a result, a large amount of gold outflowed overseas from Japan (Hane 1992: 70). In response, the Bakufu reduced the amount of gold in coins but this devaluation led to a hyperinflation. This created ill-feeling towards foreign trade among Japan’s military nobility, the samurai, and led to the emergence of a radical philosophy and movement called son-nō jō-i (revere the emperor, expel foreign barbarians). However, jō-i (expel foreign barbarians) was replaced with tōbaku (defeat the Bakufu) after fanatic samurai warriors realized the impossibility of expelling western imperial powers and sought to blame the Bakufu instead for opening the country. Eventually, southern and western provinces of Satsuma and Chōshū formed a military coalition and conducted a coup d’état to oust the Bakufu from power. Although the last Shōgun Yoshinobu proposed to surrender power to the imperial court on the condition that a government centered on the Tokugawa clan would be formed in coalition with daimyō provincial lords, Satsuma and Chōshū announced the establishment of a new government centered on the Emperor (Hall 1971: 263–4; Hane 1992: 80–81). The new government defeated the Bakufu forces and the Tokugawa dynasty ended in 1868 with the restoration of power to the Emperor (Meiji Restoration). Edo was renamed Tokyo and replaced Kyoto as the new capital (the location of the imperial palace) of Japan in 1869.

Figure 1.1 Japan’s exports and imports after the end of isolation in 1865

Source: Ishii (1994).

The new government in the Meiji period (1868–1911) adopted the national slogan of the “rich nation, strong army” to survive the era of imperialism and attempted to industrialize the country. For this purpose, the feudalistic socio-economic system was abolished. The government also invited foreign technicians to introduce new technologies and develop the infrastructure. For example, the first railroads connecting large cities such as Tokyo and Yokohama and then Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe were built (Crawcour 1989b: 394). The government also introduced foreign technologies to build factories to spin and produce a large amount of silk and cotton threads and yarns so that Japan would be able to increase exports of those products (Hane 1992: 99). In the process of promoting industrialization, private business families (merchant houses in the Edo period) such as Mitsui and Iwasaki (later Mitsubishi) were provided with several privileges and were called seishō (government merchants).

Matsukata Masayoshi, who became Finance Minister in 1881, established the Bank of Japan as the central bank in 1882. Matsukata implemented a deflationary policy and Japan experienced economic recession with a sharp drop in the prices of goods, including rice (Crawcour 1989a: 614–15; Hall 1971: 305–06). As a result, many farmers became tenants and borrowed land from landholders, who enriched themselves by both charging high tenant fees and engaging in money lending at the same time. The emergence of many poor tenants in villages as well as poor former lower-class samurai created social disturbance (Hane 1992: 100). However, after the implementation of Matsukata’s deflation policy, Japanese exports surpassed imports and there was a boom of establishing companies in the industrial sectors such as railroad and cotton spinning due to an increase in company stock transactions (the beginning of Japan’s “industrial revolution”). With a large amount of indemnity from a victory in the first Sino-Japanese War in 1894–95, the government promoted light and heavy industries by introducing the gold standard and establishing special banks such as the Industrial Bank of Japan for long-term investment and the Yokohama Specie Bank for trade finance.

It was the textile industry, through technical innovation, that occupied the central position in the establishment of Japanese capitalism (Taira 1989: 606). In 1883, Osaka Cotton Spinning Corporation began to produce cotton thread by using imported machines and steam engines, and Japan’s export of cotton thread to destinations such as China and Korea surpassed imports by 1897 (Crawcour 1989b: 423–25; Hane 1992: 140–43). After the Russo-Japanese War in 1904–05, large corporations in a monopolistic position exported cotton thread to the Manchurian market too. However, it was the silk industry that played the largest role in Japan’s acquisition of foreign currencies. Silk thread was the largest of Japan’s export goods and was exported to Europe and North America. Many small factories in agricultural areas produced silk thread and later silk textiles. Japan even surpassed China as the largest exporter of silk thread in 1909.

The government privatized public corporations except military and railroad companies and the seishō acquired several businesses including mining. These wealthy business families such as Mitsui and Mitsubishi grew further to become the zaibatsu (business conglomerates) engaged in several businesses across finance, trade, transport, mining and others. For example, Mitsui operated Miike Mine in Kyushu, the largest coal mine in Japan, and Mitsubishi built a large ship building factory in Nagasaki (Hane 1992: 100–101). However, to facilitate military expansion, the government began to operate Yawata Steel Factory in 1901 and nationalized the production of steel, considered necessary for the development of heavy industry (Hane 1992: 142). With an increasing demand for machinery from heavy industry as well as cotton necessary for the spinning industry, Japan’s imports exceeded exports by a large margin once again and its trade deficit increased to a critical level.

After the Russo-Japanese War, the overseas markets in Manchuria, where Japan acquired greater influence, and Korea, which Japan colonized in 1910, increased their importance for the Japanese economy. In the domestic market, many farmers became involved in the production of commercial agricultural products with a growth of Japanese capitalism. While landowners became “parasitic” (called “absentee landlords”) in the sense that they relied on tenant fees for their incomes without cultivating the land themselves and invested in business and company stocks, many farmers became poor tenants. In addition, wage labourers emerged with the growth of light and heavy industries. Factory workers, who were organized and mobilized by then illegal labour unions, demanded the improvement of working conditions by conducting strikes. This led to the emergence of socialism in Japan in the late nineteenth century. However, socialist political parties were severely supressed and dissolved by the government (Hane 1992: 144–8).

The Japanese economy at the end of the Meiji period and the beginning of the ensuing Taisho period (1911–25) was in a critical situation due to economic stagnation and fiscal deficits. However, with the beginning of the First World War, Japan was able to greatly increase export of cotton textile products to Asian markets, from where European imperial powers withdrew to engage in the war in Europe (Crawcour 1989b: 436–7). Japan’s export of silk thread to the US market also increased significantly. The worldwide shortage of ships and vessels allowed the ship building industry in Japan to prosper with several entrepreneurs making huge profits. With the development of steel, chemical, electricity and machinery industries, the ratio of heavy chemical industries among the secondary sector exceeded 30 per cent. Also, the number of wage labourers engaged in the secondary sector exceeded one million as a result of the growth in the heavy chemical industry.

At the beginning of the Showa era (1926–89), Japan experienced a financial crisis. In 1927, the disclosure of unhealthy financial situations of several banks resulted in panic with many depositors trying to withdraw their savings. The crisis was overcome only after the government issued a moratorium and provided rescue finance to those banks (Hane 1992: 235–6; Nakamura 1989: 456–8). However, Japan was later to experience a serious economic depression due to the fiscal restraint policy of the new administration led by Prime Minister Hamaguchi of the Minseitō Party and the Global Depression that began in the US in 1929. The Hamaguchi administration lifted the embargo on gold exports and implemented a deflationary policy to enhance the competitiveness of the Japanese economy (Nakamura 1989: 462–5). As a result, many companies went bankrupt and the number of unemployed workers increased to a significant extent. The poverty of villages also increased due to a sharp drop of agricultural products. The number of labour and peasant disputes increased as a result. Amidst this crisis, zaibatsu, which monopolized the economy through the control of several industries, including finance, retail and heavy chemical industries, deepened their connection with political parties. This gave rise to political corruption involving the zaibatsu and the parties and increased the criticism by right-wing fanatics, who included many young Japanese from poverty-stricken villages (Waswo 1989: 556). Many of them were to join the military later, as Japan saw a rise of military and right-wing fanaticism in the 1930s.

After Prime Minister Hamaguchi was physically attacked by a young right-wing fanatic in the same year (1930) of the signing of the London Naval Treaty and later died, Prime Minister Inukai of the Seiyūkai Party formed a cabinet in 1931 with Takahashi Korekiyo as Finance Minister.2 Takahashi reversed the Hamaguchi administrations’ fiscal restraint and deflationary policy and adopted a policy of fiscal expansion (so-called “Takahashi finance”). He reintroduced the embargo on gold exports and Japan’s exports increased with depreciated yen. His lax fiscal policy by issuing deficit bonds stimulated the economy, and Japan escaped from economic depression before western imperial powers did (Gao 2001: 50; Nakamura 1989: 468). The government policy to expand the military and protect strategic industries contributed to the rapid growth of heavy chemical industry in the 1930s (see Figure 1.2). For example, the government merged steel companies to create a national champion called Nihon Seitetsu Gaisha (Japan Steel Corporation). As a result, the production of steel increased. In addition, many waged workers moved into the heavy chemical industry on an unprecedented scale (Taira 1989: 611). The government also increased economic control by enacting the Important Industry Control Law in 1931 that mandated cartels (Gao 2001: 51).

Figure 1.2 Japan’s manufacturing composition, 1919–3...