![]()

1 Introduction: Understanding Adults Learning to Read for the First Time in a New Language: Multiple Perspectives

Martha Young-Scholten and Joy Kreeft Peyton

1.1 Adult Migrants with Limited Education and Literacy

You may be well aware that there are adults with limited or no ʟɪᴛᴇʀᴀᴄʏ among those who migrate to a new country. You may also know that the rates of illiteracy are slowly decreasing. Worldwide, 89.8% of males and 82.6% of females over the age of 15 are now able to read and write. However, 75% of the world’s population, 750 million individuals over the age of 15, live in poor, rural areas or conflict-torn regions and have limited opportunities to participate in formal education and limited or no literacy in the language of their home and community. Two thirds of the 750 million are women (World Demographics Profile, 2018).

Educators who work to support adult ᴍɪɢʀᴀɴᴛs with limited education and literacy observe the myriad linguistic and literacy challenges that the learners in their classes face as they seek to adapt to their new country. Meeting these challenges is affected by a range of factors, from visa requirements and constraints to availability of basic skills classes and being taught by teachers and tutors who are specifically prepared to work with this population.

Educational provision for adults with little or no formal schooling or ʜᴏᴍᴇ ʟᴀɴɢᴜᴀɢᴇ literacy is more similar than different worldwide. In most countries, for example, there is no formal qualification attached to the initial steps that learners take toward earning a qualification (e.g. Entry 1 in the United Kingdom). In some countries, unpaid volunteer tutors make an important contribution in one-on-one and small-group teaching, as well as in the classroom, and they may be responsible for their own classes.

Adult migrants who arrive in highly literate societies without the skills for living wage employment, who expect to support the education and well-being of their younger family members and to engage in the civic life of their community, need at least equal the attention from educators as those who arrive with years of schooling and high-level skills, who may be able to learn in formal educational programs, with trained, qualified teachers, and who have high standards for learning and achievement. Researchers, educators and policymakers have until recently paid far less attention to this group of ᴀᴅᴜʟᴛ ʟᴇᴀʀɴᴇʀs. On this basis of similarities in educational provision and an urgent need to share accumulating knowledge, researchers and practitioners from the countries in which these adult migrants resettle have been collaborating. This means that the annual symposium of an organization dedicated to these learners, which was founded in 2005, Literacy Education and Second Language Learning by Adults (LESLLA, http://www.leslla.org), buzzes with the thrill of a Canadian, a Finnish, an Italian, a Turkish and a US teacher or tutor discovering how much they have in common and what they can learn from each other.

Research on these learners shows that, when compared with adult migrants with some home language and literacy, their progress in literacy development is much slower (Condelli et al., 2003; Kurvers et al., 2010) and can also be slower for oral language development (Tarone et al., 2009). For decades, however, research has shown that adults can reach high levels of oral proficiency in a new language regardless of the age at which they are exposed to the language, the amount of education they have and the type of exposure that they have to the language (Hawkins, 2001). Educated adults have the advantage of knowing how to read and write in their native or other language(s), and this provides a bridge to literacy in a new language. First-time adult readers lack such a bridge. It turns out that their cognitive skills support them in laying a foundation on which to develop literacy, and they seem to follow a path similar to that followed by young children learning to read for the first time (Kurvers et al., 2010; Young-Scholten & Naeb, 2010; Young-Scholten & Strom, 2006). However, so far, only a small percentage of adult migrants who start learning to read and write for the first time in their lives, but in a second language, demonstrate progress to higher levels, and the majority struggle to develop these literacy skills and remain at or even below A1 in the Cᴏᴍᴍᴏɴ Eᴜʀᴏᴘᴇᴀɴ Fʀᴀᴍᴇᴡᴏʀᴋ ᴏғ Rᴇғᴇʀᴇɴᴄᴇ ғᴏʀ Lᴀɴɢᴜᴀɢᴇs (Kurvers et al., 2010; Schellekens, 2011).

Oral language progress is also slower for those who are not literate, because the ʟᴀɴɢᴜᴀɢᴇ ɪɴᴘᴜᴛ that they can use is initially limited to listening. If they have no literacy skills at all, they will not be able to decipher environmental print. Older migrants may process oral language input more slowly than, and not remember things as well as, their younger counterparts (Tarone et al., 2009), and they also spend less time in the classroom gaining oral language and literacy skills. In some countries, they spend considerably less time due to poor access to educational provision, work and family commitments or health issues. These factors are difficult or impossible to influence. What is possible to influence is the level of awareness, knowledge and skills relevant to their situation of the teachers and tutors who work with them. Research shows that the chances of success of migrant adult learners increase significantly when they are taught by well trained and knowledgeable teachers (Condelli et al., 2010).

1.2 Terminology Used in this Book

In the chapters in this volume, authors interchangeably use the terms ‘home language’, ᴍᴏᴛʜᴇʀ ᴛᴏɴɢᴜᴇ, ɴᴀᴛɪᴠᴇ ʟᴀɴɢᴜᴀɢᴇ, ғɪʀsᴛ ʟᴀɴɢᴜᴀɢᴇ, ʟᴀɴɢᴜᴀɢᴇ ᴏғ ᴏʀɪɢɪɴ and ʜᴇʀɪᴛᴀɢᴇ ʟᴀɴɢᴜᴀɢᴇ, to refer to the language(s) that an individual has spoken since birth or early childhood. We use ‘migrant’ throughout the volume, as does UNESCO (n.d.), to refer to individuals who resettle in a country other than their country of origin, regardless of their status (e.g. asylum seeker, refugee, chain migrant), and who have the expectation of remaining in the country. UNESCO uses ‘adult’ to refer to individuals 15 years and older and those who are past the age of compulsory or free schooling (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2016). Use of the term ‘second language’, abbreviated as ‘L2’, indicates any language (not literally the second language) acquired after early childhood, as has long been the case in the field of Sᴇᴄᴏɴᴅ Lᴀɴɢᴜᴀɢᴇ Aᴄǫᴜɪsɪᴛɪᴏɴ (SLA).

1.3 European Speakers of Other Languages: Teaching Adult Migrants and

Training Their Teachers

The chapters in this volume emerged from the third phase of a project that ran from 2010 to 2018, European Speakers of Other Languages: Teaching Adult Migrants and Training Their Teachers. Surveys conducted during the second phase of the project confirmed the lack of opportunities that teachers and tutors have to gain such knowledge and skills (Young-Scholten et al., 2015a), and between 2015 and 2018, six modules were designed and delivered twice to nearly 1000 teachers and tutors around the world. The modules can still be taken; information is available from the LESLLA website: http://www.leslla.org. Modules can also be delivered in hybrid or face-to-face mode by anyone who teaches or tutors adult migrants with limited education and literacy; contact the editors of this volume.

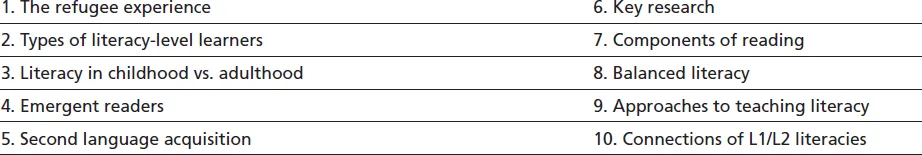

Criteria for choice of module topics to develop and offer were threefold: (1) practitioner need as revealed in a survey; (2) expertise of the EU-Speak 3 partners; (3) additional information, which included contributions to the LESLLA symposia and subsequent publications in the LESLLA proceedings, such as Vinogradov’s (2013) proposition for the knowledge base shown in Table 1.1 (see also Vinogradov & Liden, 2009).

Six module topics emerged from this process that align with the chapters in this book. Key research (6), focused specifically on migrant adults with limited education and literacy, pervades all of the modules and chapters in this book. Here, we connect the chapter topics with the other numbered points on Vinogradov’s list: Language and Literacy in Social Context (2, 8, 10); Reading from a Psycholinguistic Perspective (2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10); Vocabulary (4, 5, 7, 9); Acquisition and Assessment of Morphosyntax (5, 7, 9); Bilingualism and Multilingualism (3, 8, 10) and Working with LESLLA Learners (1, 2). The reader will note when delving into the chapters that research specifically on this learner group does not always exist, and it is often necessary to extrapolate from research on other learner populations.

Table 1.1 Knowledge base of effective LESLLA instructors (adapted from Vinogradov, 2013: 11)

See the Appendix and Chapter 5 for a description of the two surveys that led to the creation of the modules and of the countries where module participants live and work.

1.4 Literacy and the Acquisition of Linguistic Competence

This volume is, therefore, also intended to rouse readers to consider conducting their own research or working alongside established researchers to fill the gaps in what we know about this learner population. Unfortunately, the field of SLA has become less socially relevant than was the case some 40 years ago, when there was a flurry of research on migrant workers in post-industrialized countries in northern Europe, such as Germany and Sweden (see overview in Young-Scholten, 2013). Absence of an evidence base that such research would result in has serious consequences when advocating for more or specific types of educational provision for adult migrants with limited literacy. In the context of a now vast amount of research on the L2 acquisition of educated younger and older learners, there is almost nothing on the L2 acquisition of ʟɪɴɢᴜɪsᴛɪᴄ ᴄᴏᴍᴘᴇᴛᴇɴᴄᴇ by adults with limited education. When it comes to ʀᴇᴀᴅɪɴɢ, there is much more research on the process of learning to read, and there is advocacy by organizations that aim to boost literacy. But researchers and organizations focus overwhelmingly on first-time readers in their native language and not on those learning a second language with no or limited literacy in their native language. Unlike older native language ᴇᴍᴇʀɢᴇɴᴛ ʀᴇᴀᴅᴇʀs, migrant adults are learning to read for the first time, but in a second language.

One long-standing issue in SLA is whether children and adults differ fundamentally in their acquisition of language, whether there is a ᴄʀɪᴛɪᴄᴀʟ ᴘᴇʀɪᴏᴅ after which a language can only be effortfully ‘learned’ in classrooms rather than ‘acquired’ through mere exposure (Krashen, 1982, 1985). SLA researchers from the generative, Cʜᴏᴍsᴋʏᴀɴ ᴛʀᴀᴅɪᴛɪᴏɴ assume that literacy is not one of the influences on, for example, the acquisition of ᴍᴏʀᴘʜᴏsʏɴᴛᴀx or sʏɴᴛᴀx. Another long-standing issue is that of the so-called Gʀᴇᴀᴛ Dɪᴠɪᴅᴇ in analytic ability between individuals who are literate and those who are non-literate. It was not until Tarone et al. (2009) took up this issue that these two ideas (the critical period and the Great Divide) were investigated with respect to migrant adults with limited literacy, when these researchers treated literacy as a variable in their study of Somali adults’ acquisition of morphosyntax in English. Thus, Hawkins’ (2001) conclusion that education does not determine one’s ability to acquire linguistic competence in an L2 may be premature. This is important for practitioners, where the view one adopts will guide expectations of what learners are capable of.

Taking the research gap as a challenge for the field of SLA overall, Tarone et al. (2009: 1) note that because ‘we know next to nothing about [non-literate learners’] processes of oral second language acquisition’, theories are insufficient. They examined how more moderately literate vs. low-literate 15- to 27-year-old Somalis whose US residence ranged from three to seven years responded to the researcher’s ᴏʀᴀʟ ʀᴇᴄᴀsᴛs of questions they had produced. Results showed that those with moderate literacy were significantly better at recalling and accurately repeating recasts and at including ɪɴғʟᴇᴄᴛᴇᴅ ᴠᴇʀʙs in their recasts. The authors conclude that ᴀʟᴘʜᴀʙᴇᴛɪᴄ ʟɪᴛᴇʀᴀᴄʏ has an undeniable effect on the acquisition of L2 morphosyntax, and they also consider whether and if so, how, literacy might influence ᴡᴏʀᴋɪɴɢ ᴍᴇᴍᴏʀʏ ᴄᴀᴘᴀᴄɪᴛʏ (see also Gathercole & Baddeley, 1989; Reis & Castro-Caldas, 1997 on non-literate ɴᴀᴛɪᴠᴇ sᴘᴇᴀᴋᴇʀs; Juffs & Rodríguez, 2008 on second language learners with limited literacy).

Considerably more research is needed before solid conclusions can be drawn about the influence of literacy on the acquisition of linguistic competence. Also rare are studies that look at the linguistic competence of literate vs. non-literate native speakers of a language. One example is Mishra et al. (2012), who describe their study of very low-literate and high-literate adult Hindi speakers in Uttar Pradesh, India, from the same Dalit community. They used a technique referred to as ᴇʏᴇ ᴛʀᴀᴄᴋɪɴɢ, in which they presented the study participants with a visual display of objects and played sentences to them. While participants were listening to the sentences and looking at the display, the researchers measured for each sentence where their eyes moved and watched to see if they anticipated what was going to come next by moving their eyes. The eye tracking showed that the participants with limited literacy were significantly slower at using the cues in the sentences to look at the objects in the display and to anticipate what would come next. However, in the analysis of their results and in their critical review of claims made about the influence of literacy on the mind and on language, Mishra et al. note that it is not clear whether literacy per se affects individuals’ ability to use cues to anticipate information or whether it is because reading allows for faster processing (250 wpm) than listening to spoken language (150 wpm).

The dearth of basic research on adult migrants with limited literacy has consequences for what practitioners believe learners are capable of. Laborious, systematic observation and experimentation have given us wonderful stories about the capabilities of living organisms, from babies to crows. But laborious, systematic observation and experimentation on these learners’ acquisition of linguistic competence is, to date, rare. For those who benefit from this volume and would like to expand their knowledge of these and other issues, Wright et al. (2018), Mind Matters in SLA, is a good place to start. Hawkins (2018) is another volume dedicated to applying cutting-edge ideas to the exploration of all aspects of the acquisition of morphosyntactic and syntactic competence in a second language. Another source is the OASIS project, which is dedicated to providing accessible summaries of SLA research (https://oasis-database.org/about).

1.5 Chapters in This Volume

As mentioned above, the chapters in this volume follow the topics of the online EU-Speak modules offered to practitioners.

In Chapter 2, Language and Literacy in Social Context, Minna Suni and Taina Tammelin-Laine describe the contexts in which adult learners with limited education and literacy live and learn, the impact that this has on their learning and ways that practitioners working with these learners can serve them successfully. They provide examples of research and practice primarily from Finland, the context in which they work, and other Nordic countries. Readers will notice commonalities with their own situations, confirming the premise that practitioners working with this group of learners are similar across countries in many ways.

Chapter 3, Reading from a Psycholinguistic Perspective, is the first of three chapters that focus on aspects of the linguistic competence that underpins reading comprehension. Marcin Sosiński describes the process of reading skills development, including how these link to phonological, phonemic, morphological and syntactic awareness, and pedagogical approaches that can be used to promote learning to read words and longer texts. While there is some research that focuses on the population of migrant adults with little or no formal education, much of the research discussed in this chapter comes from studies of children learning to read.

Chapter 4, Vocabulary, by Andreas Rohde, Kerstin Chlubek, Pia Holtappels, Kim-Sarah Schick and Johanna Schnuch, covers vocabulary and details how learners without literacy, young children, effortlessly amass an impressively vast store of words before they begin to learn to read. Although there is limited research on the vocabulary development of migrant adults, the research presented in this chapter is highly relevant to learners who cannot yet learn words from context during reading, cannot yet use text-based dictionaries and do not have the written-text-based strategies that educated learners have at their disposal. The chapter concludes with applications and implications for teachers and tutors.

Chapter 5, Acquisition and Assessment of Morphosyntax, by Martha Young-Scholten and Rola Naeb, covers a second aspect of linguistic competence that is fundamental to learners being able to comprehend text: morphosyntax. Morpho-refers to ғᴜɴᴄᴛɪᴏɴᴀʟ ᴍᴏʀᴘʜᴏʟᴏɢʏ – words, ᴘʀᴇғɪxᴇs and sᴜғғɪxᴇs that mark grammati...