eBook - ePub

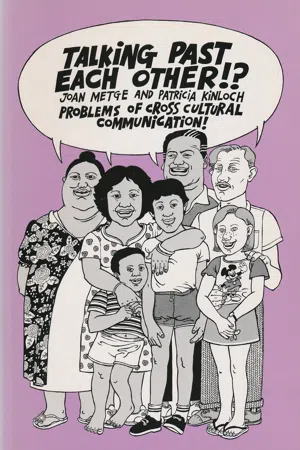

Talking Past Each Other

Problems of Cross Cultural Communication

- 62 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Where numbers of different cultural groups come together, misunderstandings and tensions can arise, even where there is the greatest goodwill on both sides. Sometimes even those involved are unable to explain why. In this book the authors set out to explore the situations and contexts in which cross cultural misunderstandings can occur. Talking Past Each Other was first published in 1978 and has been read widely and reprinted regularly.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Talking Past Each Other by Patricia Kinloch,Joan Metge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Anthropologie culturelle et sociale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Talking past each other

It has become fashionable to refer to New Zealand as a multicultural society, which is one way of saying that the population comprises more than one cultural group. It does not mean that a majority of New Zealand citizens are knowledgeable about other cultures than their own. Certain minority groups, notably the Maoris and other Polynesians, are generally identified as falling below the average level of education and socio-economic achievement.1 Those engaged in the provision of services in various fields—early childhood care, schools, health care, social welfare, marriage guidance, etc.—are concerned that these groups are not taking full advantage of the services they offer. But efforts to encourage greater involvement run into difficulties. Without denying the contribution of other factors (such as social and economic pressures), we should like to focus attention on the problems that arise because of cultural differences, especially those which are not recognised as such.

By and large the wide range of official and voluntary services available to citizens in New Zealand are built upon premises, research and values derived from the majority (Pakeha) culture. Those staffing these services are predominantly Pakeha and vary widely in their knowledge of other cultures. Because of this members of minority groups often shy away from these services altogether, whether from feelings of inadequacy or because they see them as threatening their own cultural values. Or else they seek out particular branches, because of the presence of staff members knowledgeable about and/or sympathetic to their group, because of congenial informality, or because of the reassuring predictability of a formal set-up. Where members of different cultural groups do come together in formal and informal situations, misunderstandings and tensions arise even where there is the greatest goodwill on both sides, misunderstandings which the parties themselves find it hard to explain.

On the basis of our experience working with Maoris and Samoans in their dealings with Pakehas, we the writers of this paper have become convinced that a good deal of miscommunication occurs between members of these groups because the parties interpret each others’ words and actions in terms of their own understandings, assuming that these are shared when in fact they are not—in other words, because of cultural differences that are not recognised because we all take our own culture very largely for granted and do not question its general applicability.2 A culture can be simply and usefully defined as ‘a system of shared understandings’—understandings of what words and actions mean, of what things are really important, and of how these values should be expressed.3 These understandings are acquired in the process of growing up in a culture and most become so thoroughly internalised that we cease to be aware of them, coming to think of them (if at all) as ‘natural’ or at least ‘second nature’, not only the right but the only conceivable way of doing and looking at things, identifying ‘our way’ as ‘the human way’. We are more ready than we used to be to recognise and respect cultural differences—where they are particularly striking. The Maori tangihanga for instance is nowadays recognised as an acceptable way of mourning the dead and no longer widely denigrated as pagan, morbid and wasteful. But differences that are less obvious and involve individuals rather than groups frequently go quite unrecognised. When Maoris, Pakehas and Samoans act on the assumption that they give particular words and actions the same meaning while actually giving them different ones, they ‘talk past each other’, misread each others’ words and actions, respond inappropriately, and judge each other as stupid, odd or rude in the light of their own standards. And because this happens below the level of conscious awareness they can go on making the same mistakes indefinitely, failing to connect, feeling irritated and confused, unless someone opens their eyes to what is happening.

During 1977 we set out, separately but in association, to check and develop this insight by observation, interviews and group discussions involving Maoris, Pakehas and Samoans separately and together.4 The Maoris and Samoans we approached responded immediately and warmly, quickly recognising what we were talking about from their own experience. They were keen to explore the topic, so keen that they invited us to meetings and arranged others especially for the purpose. As they talked, and especially as they responded to the draft abstract of this paper, they brought more and more examples to their consciousness and ours. Valuable contributions also came from Pakehas involved in early childhood care situations.5 The body of this paper represents the fruit of these discussions, integrated with and checked by our own experience. When we speak of Maoris, Pakehas and Samoans in the following pages we are talking, in general terms, of the ideas and practices typical of Maoris, Pakehas and Samoans as groups. We do not mean to imply that every single person who could be identified as Maori, Pakeha or Samoan necessarily holds the ideas or behaves in the way described. We do, however, believe that the ideas and behaviour in question are sufficiently common among members of each group for themselves and/or others to consider them characteristic, and should at least be considered in any attempt to understand inter-group relations.

VERBAL AND NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION

Members of all three groups talk with their bodies as well as their tongues, but Maoris and Samoans emphasise ‘body language’ more and verbalisation less than Pakehas. Pakehas who define communication primarily in terms of verbal expression typically find Maoris and Samoans unresponsive and ‘hard to talk to’, while all the while they themselves are failing to pick up much of the communication directed their way because they are ‘listening’ with their ears instead of their eyes. To Maoris and Samoans, Pakehas often seem deaf to what others are trying to tell them, while at the same time they are ‘forever talking’. This is not of course objectively true, but the quiet ones are submerged by the talkers. So many of the words Pakehas use seem unnecessary, so many of the things they say seem trivial, that Maori and Samoan listeners often ‘cut out’—and then respond inappropriately because they did not ‘get’ the message.

INDICATING AGREEMENT AND DISAGREEMENT

Pakehas usually say ‘yes’ and ‘no’, reinforcing the words with a nod or a shake of the head. They accept the words without the action; but regard the actions without the words as inadequate and rude except in situations of intimacy. Maoris and Samoans on the other hand frequently dispense with the verbal forms and rely on gestures only without considering this rude. They recognise the nod and headshake as ‘yes’ and ‘no’ but commonly use other indicators: an upward movement of the head and/or eyebrows for ‘yes’, and an unresponsive stare—straight ahead or down at the feet—for ‘no’. These are easily misread. A Pakeha infant teacher related how she found she was continually repeating herself to her predominantly Polynesian class. She established that she was doing it in response to the raised eyebrows gesture which she had interpreted as ‘Please say it again’, and realised that they were in fact signalling ‘Yes, we understand’. However, though Pakehas so often interpret raised eyebrows as a question, if you watch carefully, you will find that they use variations of it with other meanings, especially to indicate recognition, for instance if friends meet where words are precluded by distance, too much noise or a rule of silence.

OTHER KINDS OF ‘BODY LANGUAGE’

The shrug is another signal which is frequently misinterpreted. Pakehas use it in several forms with different meanings, but in dealing with members of other cultural groups they seem primarily to read it as meaning ‘I don’t care’. Many Maoris recall being punished for insolence at school even in the primers for hunching their shoulders up under their ears, a gesture which in their intention and experience meant simply ‘I don’t know’.

Maori informants also speak of the frown and the sniff as gestures often misunderstood by Pakehas. They use the frown to indicate not only disapproval but also (in the form of a rapid, repeated depression of the eyebrows) puzzlement and a plea for help, while the sniff indicates admission of and apology for a mistake more often than disdain.

Signals for ‘Come here’ vary cross-culturally too. Where Pakehas move the hand up and in towards the chin with the palm turned up, Samoans and most other Polynesians move the hand down and in towards the chest with the palm turned downwards. They also use a nod with the same meaning. Both these gestures are likely to be misinterpreted by Pakehas. One informant recalled seeing a fight erupt in a hotel bar in this way. A Niuean accidentally bumped and spilled the glass of beer a Pakeha was holding. When he apologised, the Pakeha said ‘It doesn’t matter’ and waved his apology down. The Niuean interpreted the gesture as meaning ‘Come here’ and advanced on the Pakeha, who interpreted his advance as a threat and decided to get in first.

Maoris in particular use the discreet cough to convey a range of messages during speech-making on the marae. And when Maoris and Samoans want to send spouses or children off on an errand they first catch their eye and then move head and eyes sideways in the required direction.

Compared with Pakehas, most of whom limit physical contact outside the rugby scrum to situations involving close kin and friends on the one hand or sexual encounter on the other, Maoris and Samoans characterise themselves as ‘very touching people’. They extend the hand of friendship to all comers quite literally: a gathering of Maoris or Samoans expects new arrivals to shake hands with all present before sitting down. Where the gathering is large they will at least shake hands with those passed on the way to a seat. A hand laid on hand, arm or shoulder or a generous hug is variously used to convey sympathy, support, gratitude, apology, and a desire for friendship as well as recognition of an established relation. When Patricia Kinloch arrived at a school staffroom to interview a Samoan teacher, the latter had forgotten she was coming but immediately put an arm round Patricia’s shoulder, began to introduce her, and then had to ask her name. ‘Some friend you are,’ quipped one of the other Polynesian teachers, but the message of intended friendship and support was clear. Because they keep such gestures for a few firm friends, Pakehas often misinterpret Polynesian use of them as ‘hypocritical’ or ‘meaningless’, but this is far from the case. On the other hand, Polynesians often misjudge Pakehas as ‘snooty’ and ‘stand-offish’ because they do not engage in such contact.

THE USE OF THE EYES

The use of the eyes in interpersonal encounter is a fruitful field for misunderstanding. Pakeha children are explicitly instructed to ‘look at’ anyone they are talking to and to look superiors in particular ‘in the eye’. Looking at people signals interest and undivided attention. It also indicates you have nothing to hide. To let your gaze wander from a vis-a-vis is interpreted as boredom and (worse) bad manners for letting it show. To look away from a questioner is a sign of evasion or guilt. Maoris and Samoans on the other hand consider it actually impolite to look directly at others when talking to them. They say that it tends to put the two concerned into a relation of opposition, encouraging the development of conflict and confrontation. It also tends to cut out the others in the group. So they rest their gaze elsewhere, slightly to one side, on the floor, ceiling or distant horizon, or they even close their eyes altogether. In this way they ‘soften’ whatever is said and make it easier to concentrate on the content. Unfortunately behaviour intended to avoid offence is often ‘read’ by Pakehas with other ideas as rudeness or shiftiness. At the same time, Pakehas make Polynesians uncomfortable by the unrelenting way they fasten their eyes on their faces, so that there is no escape or respite from the pressure of their personality.

STANDING AND SITTING

Pakehas take for granted the idea of stand...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-title

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Talking past each other

- Introducing ‘Talking past each other’

- Further Reading

- Copyright