eBook - ePub

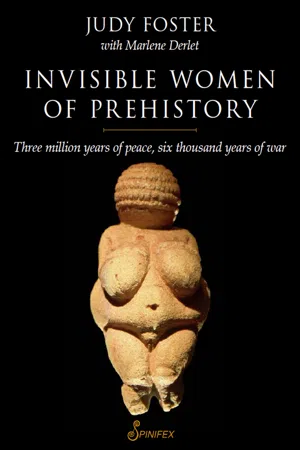

Invisible Women of Prehistory

Three Million Years of Peace, Six Thousand Years of War

- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Invisible Women of Prehistory

Three Million Years of Peace, Six Thousand Years of War

About this book

Based on many years of research into ancient history and prehistory, this insightful tome argues that three million years of peace—a period when women's status in society was much higher than it is now—preceded the last 6,000 years of war during which men have come to hold power over women. The book challenges the idea accepted in academia that history is a linear development in which society is steadily moving out of a violent and patriarchal past to a more equitable and peaceful future, and it reexamines both the archaeological work of Marjia Gimbutas and recent research into the prehistories of Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Australia and Oceania.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Invisible Women of Prehistory by Marlene Derlet,Judy Foster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THE PREHISTORIC FEMALE PRINCIPLE:

THE GODDESS OF OLD EUROPE

THE GODDESS OF OLD EUROPE

PREHISTORIC CAVE PAINTINGS

1. Ariege cave painting, France, 27,000-14,000 BP

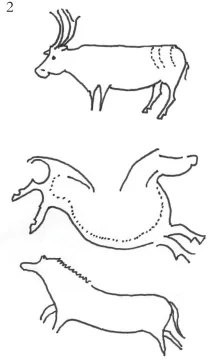

2. Cave paintings, Altamira, Spain; Lascaux, France

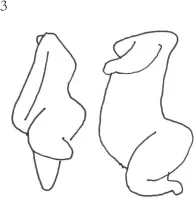

3. Pech Merle figure, France, c. 20,000 BP

(Source 1–3: Pericot-Garcia, Luis et al., 1967)

(Source 1–3: Pericot-Garcia, Luis et al., 1967)

4. Spanish cave art, 8,000 BP

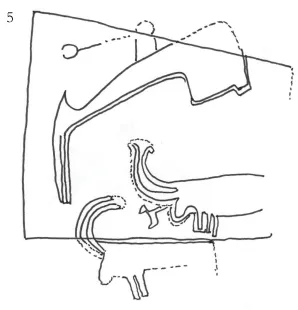

5. Axe and bulls, Gavrini, Brittany, 6,000 BP

(Source 4–5: Gimbutas, Marija, 1989)

(Source 4–5: Gimbutas, Marija, 1989)

All line drawings © Judy Foster, 2013

CHAPTER 1

THE THEORY OF MARIJA GIMBUTAS

Our search for the origins of visual symbolism led to the accidental discovery of The Language of the Goddess (1989), the first of three major works by Lithuanian archaeologist and mythologist Professor Marija Gimbutas. This impressive text illustrates the symbolism and records the underlying meaning of the prehistoric female figurines and associated objects belonging to a prominent female deity whom Marija Gimbutas named the ‘great goddess’. In her second book, The Civilization of the Goddess (1991) she noted the presence of female figurines first appearing in the Upper Palaeolithic period. She recorded in great detail the habitations and cultures in the Neolithic world of Old Europe;1 these were peace-loving and communal agricultural societies in which women were respected, even revered, and highly visible until as recently as 6,500 BP. Marija Gimbutas explained how these societies faded away or ended, often abruptly, as new horse-riding invaders proceeded to spread across Europe and Asia over the next thousand years, bringing with them new hierarchic and violent ideas and practices. So began the present patriarchal period.

In her third and final book, The Living Goddesses (2001), published after her death, Marija Gimbutas provided what has to be conclusive evidence of women-centred societies in prehistory, particularly in eastern Europe, reaching as far west as England and Ireland. She recorded thousands of female figurines and other artefacts reinforcing the powerful presence of the female principle. She followed the development of the multi-faceted goddess cultures from 9,000 years ago through the emergence of the Indo-Europeans and into the early historical period, observing the goddess’s changing and diminishing role until recent times when the goddess has become almost invisible.

This unknown world before written history was revealed through the skills of archaeology, anthropology, linguistics, and mythology, combined disciplines which Marija Gimbutas named ‘archaeomythology’, and she used these to reinterpret the period in prehistory from 10,000 BP to 2,000 BP. It was not enough for her just to record the material culture of a society; she also found it essential to utilise other non-material research to discover the true picture of an archaeological site. Marija Gimbutas explained to Joan Marler that this different approach to the archaeology of Europe came about because of her background in Lithuania surrounded by folklore, mythology, and living goddess traditions, and her exposure to both Indo-European sky gods and earlier mythologies which were deeply connected

with the Earth and its mysterious cycles that was still alive in the Lithuanian countryside … The rivers were sacred, the forest and trees were sacred, the hills were sacred … The people still followed traditional ways of working the land.2

She discovered that the great goddess who was to be found everywhere in Indo-European religions had been inherited from the earlier religions of Old Europe, and she came to recognise that there were two distinct systems: firstly, that of the peaceful Palaeolithic and Neolithic women-centred Old Europeans; and secondly, the aggressive male-dominant religious systems of the Indo-Europeans. It became necessary to study symbols through their context and association, and it was in this way that she discovered how the Old European cultures experienced long-term peaceful living with egalitarian social structures and non-material value systems of benefit to all. Until Indo-European contact these were, and where possible, still are, the values of most indigenous people around the world. Although Marija Gimbutas spent 25 years examining the visual symbolism of Old Europe, she felt she had only just begun the search, and her greatest wish was for succeeding scholars to discover the full story of the Old Europeans.

While a researcher at Harvard University, Marija Gimbutas led several excavations in Europe, Yugoslavia and Italy over 13 years. In her first report, The Gods and Goddesses of Old Europe (1974), she began to develop her hypothesis concerning a Palaeolithic and Neolithic multi-dimensional female deity, Indo-European origins and the beginning of the patriarchal period. She always read other excavation reports in their original language so that her overview of the general picture was as accurate as possible.

In her excavations Marija Gimbutas found many artefacts including female sculptures in household sites in positions which suggested they may have had religious significance. She began to notice certain often-repeated forms of symbolism, such as bird and snake imagery, associated with these female goddess forms which suggested a symbolic meaning. It was already known that from earliest times humans were aware of metaphysical forces such as spirits in various animal or other forms, or ancestral beings or deities, often manifested in ritual burial practices or incised rock art imagery that were concerned with some religious aspect. She found that metaphysical beings in the Neolithic context were female and noted not only for their birth-giving and nurturing aspects, but also for their guiding roles as carers of the community.

It also became clear to Marija Gimbutas that Palaeolithic and Neolithic (goddess) female sculptures expressed many more functions than those of fertility and motherhood. She defined the goddess as unifying all natural things, as a metaphor for earth’s powers, and the expression of the power of nature through plant, animal and human life. In The Language of the Goddess (1989) she explains that the goddess religion was “a cohesive and persistent ideological system”3 aspects of which live on into the present time despite being eroded away within the historic era.

Marija Gimbutas regarded as a serious ongoing problem the critical Western male association of female figurines with ‘fertility’ rites and cultic imagery when interpreting societies of the deep past. Such views are more likely to reflect pervasive masculinist and mainstream prejudices, and they assume prehistoric cultures to be similar to our own; it is still hard for most people to admit that a very different world could have existed.

Earlier women-centred earth/nature/goddess symbolic systems in which women and men each had their own role and their own power, were found to be very different to those in the warrior period, where all the gods were warriors. The most important gods in the new Indo-European era were the ‘god of the shining sky’, the ‘god of the underworld’, and the ‘thunder god’, while the goddesses were demoted to become powerless brides, wives or maidens lacking any creative or social powers. These later Indo-European patriarchal cultures were found to be considerably less sophisticated than the earlier goddess culture, and this was clearly demonstrated by the disappearance of the refined and beautiful Neolithic artefacts which, evidence suggests, were replaced by the rather less sophisticated tools of the violent Bronze Age warriors.

EXAMPLES OF PREHISTORIC FEMALE FIGURINES

1. Figurine, Malt’a, Siberia

2. Lespunge figurine wearing her string apron

3. Two calcite figurines, France, 23,000 BP

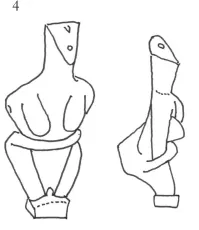

4. Two views of a Malt’a figurine, 7,500 BP

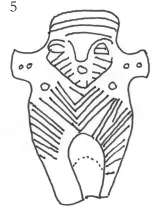

5. Vinča bird goddess, 7,000 BP

6. Romanian ritual vase, 7,000 BP

7. Two Vinča figurines, 6,500 BP

(Source: Gimbutas, Marija, 1989)

(Source: Gimbutas, Marija, 1989)

All line drawings © Judy Foster, 2013

Most (male) archaeologists also assume hierarchical interpretations for village layouts in the Neolithic period when the property of the peaceful agriculturalists had been communally owned; but it was the Proto-Indo-Europeans who introduced individual male ownership of people and goods. Social organisation became class-based, led by powerful wealthy kings or chieftains; women became male property and war victims were reduced to slavery. Villages now had to be surrounded by defensive fortifications in order to prevent unauthorised access or invasion. Agriculture and war did not start at the same time in the past: agriculture was developed over 4,000 years before the emergence of the pastoralist Proto-Indo-Europeans.

Since Marija Gimbutas completed recording her discoveries other evidence has emerged which supports her theory. For example, archaeologist David Anthony (1998), when studying horses’ bit wear in the Russian steppe region, also identified the original Proto-Indo-European homelands in this area north of the Caucasus, a scenario similar to that described by Marija Gimbutas. He examined the jawbones of horses found in the earliest graves on the steppes and dated them to about 6,000 BP,4 providing a date for the earliest horse riding, and for the homelands of the Proto-Indo-Europeans. His dates also align in every way with those of Marija Gimbutas.

In The Mummies of Urumchi (1999) Elizabeth Barber provides interesting and convincing textile evidence for the steppe homelands of the Proto-Indo-Europeans, and includes comparisons of looms and thread used in the Indo-European homelands and surrounds as against those used elsewhere in Eurasia. This research supports Marija Gimbutas’s identification of the Proto-Indo-Europeans’ homelands and their aggressive activities as they spread outward into the surrounding Neolithic European farming lands.

Geneticist Luigi Cavalli-Sforza (2000) has acknowledged the theories of Marija Gimbutas concerning the origins of Indo-European speakers. He also notes that genetic evidence supports David Anthony’s more recent discoveries of the rise of horse riding in southern Russia. He is enthusiastic about the idea of multidisciplinarity (such as Marija Gimbutas’s use of archaeomythology), and considers there are major benefits to be gained by involving many disciplines when examining a field of study.

The inspired scientific investigations of Marija Gimbutas have opened up to us new ways of seeing and understanding our past, but have upset many conservative (male) researchers, most of whom still refuse to recognise her discoveries, even as new evidence continues to support them. She has been greatly respected by European scholars for her meticulous body of work. In 1963, Marija Gimbutas became emeritus Professor of European Archaeology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) where she worked until she retired in 1989. Up until her death in 1994, she remained satisfied that her theories were soundly based, but anticipated that it would take 30 years or more for her theories to become generally recognised.

Achievements of Marija Gimbutas

A number of researchers have endorsed the greatest achievements of Marija Gimbutas.5 Starha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- A Timeline of Human Prehistory

- Part One: The Prehistoric Female Principle: The Goddess of Old Europe

- Part Two: The Indo-Europeans: ‘Civilisation’ and History Begin

- Part Three: The Hidden and New Worlds: Prehistories, the Female Principle and Indo-European Influences

- Conclusion: Weaving the Threads

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Backcover