- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Documentary Filmmaking for Archaeologists

About this book

Documentary filmmaker Peter Pepe and historical archaeologist Joseph W. Zarzynski provide a concise guide to filmmaking designed to help archaeologists navigate the unfamiliar world of documentary film. They offer a step-by-step description of the process of making a documentary, everything from initial pitches to production companies to final cuts in the editing. Using examples from their own award-winning documentaries, they focus on the needs of the archaeologist: Where do you fit in the project? What is expected of you? How can you help your documentarian partner? The authors provide guidance on finding funding, establishing budgets, writing scripts, interviewing, and numerous other tasks required to produce and distribute a film. Whether you intend to sell a special to National Geographic or churn out a brief clip to run at the local museum, read this book before you start.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

|

1

FORMING THE ARCHAEOLOGIST/DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKER TEAM |

The Archaeologist/Documentary Filmmaker Paradigm

ADOCUMENTARY FILM IS A STORY that has found its storyteller. Several years ago, documentary filmmaker Professor Pat Aufderheide (American University) astutely wrote, “I believe the role of the filmmaker will be increasingly to work in collaborative partnerships with people who have great stories to tell, passionate convictions, [and] inside access” (Aufderheide 2006:14). The archaeologist/documentary filmmaker paradigm certainly seems like a natural fit!

Documentaries are truthful stories about people, places, events, and things. A successful documentary is an exposition that is as compelling as it is factual. The documentary filmmaking crew creates a story with a noteworthy beginning, a dynamic middle that includes some twists and turns, and then a satisfying ending (Bernard 2011:2–3).

A documentary is not an exercise of parading one “talking head” after another in front of the camera. Barry Hampe, in his book Making Documentary Films and Videos: A Practical Guide to Planning, Filming, and Editing Documentaries, insists that a documentary is a “presentation of evidence—the truth” and functions primarily as a visual argument (Hampe 2007:13). The partnership of the archaeologist and the documentary filmmaker helps to ensure that the subject matter is portrayed accurately and that a proper balance is achieved utilizing the visual argument integrated with interviews and narration.

Most documentary filmmakers, whether employed by network or cable television firms or simply affiliated with local independent video companies, have a primary drive: they want intriguing stories to broadcast! Most documentarians will tell you they also want to be challenged, to be involved in a project that will engage them, one that is exhilarating and will motivate them to do something extraordinary.

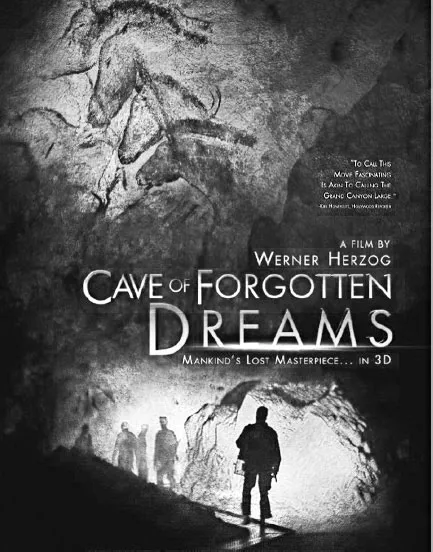

There are many kinds of documentary filmmakers with whom an archaeologist might pursue a collaboration. Some documentarians work for large production houses and may have some other type of funding as well, whether from commissioning stations, government agencies, foundations, or corporations. They may even have a technical support team. Others are independent filmmakers who have to be really creative to secure a contract to produce a film. Regardless, practically all documentarians look for terrific stories that have national or international impact (Bernard 2011:7) (Figure 1.1). Their goal might be for a theatrical release such as Werner Herzog’s 2007 documentary, Encounters at the End of the World, about those dedicated scientists who conduct their research in the harsh environment of Antarctica, or his 2010 3-D documentary, Cave of the Forgotten Dreams, about the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave art of southern France that dates back over 30,000 years ago (Figure 1.2). Other big-time filmmakers seek to have their documentaries broadcast on network or cable television, such as Spike Lee’s 2006 HBO-released documentary about Hurricane Katrina called When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts. Independent filmmakers frequently conduct their work to reach regional and local audiences. Like internationally and nationally esteemed documentarians, independent documentary filmmakers strive for awards and other critical acclaim at film festivals held around the country and the world. An emerging outlet for documentary filmmakers is through YouTube and other sites on the Internet (Bernard 2011:7).

Sometimes, an independent documentary filmmaker or a staff member of a production company working for a television network might approach an archaeologist about collaborating on a documentary or television production. David Starbuck, an archaeology professor at Plymouth State College in New Hampshire, specializes in eighteenth-century battlefield sites in the northeast United States. He has worked with the History Channel, The Learning Channel’s Archaeology series, and National Geographic Channel on several archaeology television productions. Starbuck says, “A number of producers learned about our work because of an Associated Press release that was printed across the country” (personal communication, 2012). Television production companies likewise approached him following the publication of a magazine article on one of his archaeological excavations: “All of the programs in The Learning Channel’s Archaeology series (which aired in 1993, 1994, and 1995) were based on articles that first appeared in Archaeology magazine. So each of these shows was based on separate articles that I had published in the magazine. The show’s producer, New Dominion Pictures, was put in touch with me by the editor of the magazine” (personal communication, 2012). Thus, getting the word out about an archaeology project and establishing oneself as the expert on that topic certainly helps in attracting documentary filmmakers and television production companies. “If you have an interesting story to share, public audiences absolutely love joining with you in the thrill of discovery,” says Starbuck (personal communication, 2012).

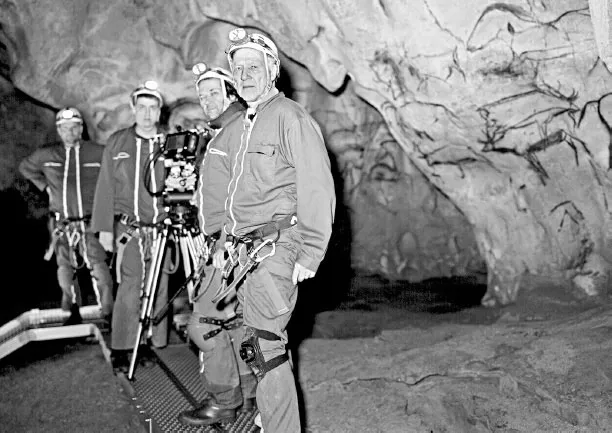

Figure 1.1: Award-winning documentarian Werner Herzog with Peter Zeitlinger and documentary film crew with rock art during the production of the documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams (credit: Marc Valasella & Creative Differences).

Figure 1.2: One of the most talked about archaeology-related documentaries in years is Werner Herzog’s production Cave of Forgotten Dreams, a 3-D documentary (credit: courtesy of Sundance Selects).

Pursuing the Documentary Filmmaker

So, archaeologists can sit around waiting for a television production company to contact them, or those with a first-rate story just waiting to be told can actively pursue a documentarian or television production firm for a collaborative endeavor.

How does one chase down a documentary filmmaker? If you are looking for an independent filmmaker from your geographical area, there are numerous ways to find one. Start by checking the Internet via a Google search, or go old-school and consult the Yellow Pages in your local phone book for video production companies. Find local or regional film festivals and then attend one or two of them. Most film festivals have a documentary category, and frequently they feature regionally produced documentaries. Watch a few, and if you find a documentary style you really like, contact the film festival to hunt down that documentarian whose work you enjoyed. Many larger cities also have film forums which host monthly screenings of films. Visit your local film forum and absorb as much as you can. Who knows, you might meet some local film aficionados who can direct you to a documentary filmmaker living near you.

You might also want to visit and even join Withoutabox, a website devoted to helping filmmakers submit their movies and documentaries to film festivals in the United States and elsewhere. It was founded in 2000. In 2008, IMDb, a division of Amazon, acquired Withoutabox. You can become a member of Withoutabox (there is no cost to register) and thus uncover more information about what film festivals may be located near you. The website allows you to search over 3,000 film festivals worldwide. Members can also sign up to receive e-mail notices on upcoming film festival entry due dates and other relevant film festival information. Though this website is primarily used by filmmakers, it is nevertheless a very useful tool for anyone interested in documentary filmmaking.

You can also seek out local corporate video production companies that make television commercials or video productions for websites. They have the technical skills to make a documentary, but possibly are never approached to do so.

If you want to find an established documentarian, consult the International Documentary Association website (www.documentary.org). The IDA is a not-for-profit corporation that was established in 1982 to support programs for documentary filmmaking. They have a wonderful quarterly magazine and an awards program for documentaries. By perusing their website, you may find a documentarian who would be open to a documentary project partnership.

Most community colleges teach a basic course in filmmaking or video editing. These colleges might have a filmmaking club and may even have a campus television studio. Find your local community college and check its website. It’s not uncommon to find a wealth of filmmaking talent on a community college campus. Any of these folks might like to partner with you to produce a short documentary on your local archaeology project.

If you locate a local video production company, you really need to unearth a little information about the firm before contacting them. What is the core of their business? Do they have up-to-date video cameras and computer editing equipment as well as experienced personnel with sufficient computer editing skills to complete a documentary?

Once you find your documentarian, you should set up a meeting. Before you meet, you should develop your pitch to the documentary filmmaker (see Chapter 8). In preparation, view as many different types of documentaries as possible to get a general understanding of the kind of documentary styles that communicate information and are also sterling storytelling vehicles.

When you find a corporate video or documentary filmmaker, you will need to craft a well-written but short letter, essentially a tease. There is no standard tease letter, but we can give you some general hints to help you in drafting that all-important letter. This is the beginning of the all-important relationship. Be direct. Tell the filmmaker you are interested in collaborating on making a documentary about one of your archaeology projects. Briefly cite your professional credentials and convince the filmmaker you are an authority on that topic and that you desire to work with the filmmaker in a collaborative project. Be ready with a catchy title for your documentary, too, and provide the gist of your documentary story in a couple of sentences. Do not overwhelm the filmmaker with details. Just provide a tease. Ask to set up an appointment. You can send your tease letter by U.S. mail or e-mail. If needed, follow up your letter with a telephone call. Remember, when you approach the filmmaker, you are starting a relationship to pique his or her interest. The documentarian wants to know that the archaeologist is well respected, knowledgeable in his or her field, and, if possible, is one of the experts on that subject.

Before we move on to suggestions for developing your formal pitch to a documentarian, the next chapter provides a little background on the history of documentary filmmaking. It will give you a sense of how and when documentaries started.

Documentary Filmmaking for Archaeologists, by Peter Pepe and Joseph W. Zarzynski, 17–22. © 2012 Left Coast Press, Inc. All rights reserved.

| 2 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE DOCUMENTARY FILM GENRE |

IN CHAPTER 1, WE GAVE A BRIEF DEFINITION of the word “documentary.” It is now time to describe the word in greater detail, give a brief history of filmmaking development, outline the history of documentary films, and review the introduction of television, since it is one of the prime conveyers of documentaries.

What a Documentary Is

Simply stated, documentaries are truthful stories about people, places, events, and things set in the past or present. Before the advent of television and video, documentaries were called “documentary films” because they were shot on film stock, the medium of that earlier time. Today the term “documentary” is more often used to describe the genre.

Archaeology documentaries are essentially stories about the past and the people who lived during the event or time being documented. Many Americans are intrigued about history and about the science of archaeology, too. Thus, it should not be surprising that Hollywood also has a love affair with the past. According to archaeologist Vergil E. Noble, who wrote a section in the 2007 book Box Office Archaeology: Refining Hollywood’s Portrayals of the Past (edited by Julie M. Schablitsky), of the movies produced in the twenty-five-year period from 1981 to 2006, more than half of the 125 films nominated for an Oscar for Best Picture were set in a time before the present. Those Hollywood blockbusters covered periods from the Roman Empire to the Vietnam War (Noble 2007:226). Yes, you certainly could say that Americans do love movies and documentaries about yesteryear.

It is believed that the word “documentary” was coined by John Grierson (1898–1972), a Scotsman who wrote a review of Robert J. Flaherty’s film about Polynesia called Moana. Grierson’s review was published in the New York Sun newspaper on February 8, 1926, under Grierson’s pen name at the time, “The Moviegoer.” In his review, Grierson wrote, “Of course Moana, being a visual account of events in the daily life of a Polynesian youth and his family, has documentary value.” The term soon caught on to describe nonfictional films. John Grierson would...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1: Forming the Archaeologist/Documentary Filmmaker Team

- CHAPTER 2: A Brief History of the Documentary Film Genre

- CHAPTER 3: The Introduction of Home Video, Television, and Documentary Filmmaking

- CHAPTER 4: Production Equipment and Screen and Standards Formats

- CHAPTER 5: The Popularity of Documentaries

- CHAPTER 6: The Stages of Documentary Film Production

- CHAPTER 7: Considering Making a Documentary—Your Idea and Title

- CHAPTER 8: Pitching a Proposal and Writing a Treatment

- CHAPTER 9: Developing a Budget and Securing a Contract

- CHAPTER 10: Shaping Your Archaeological Documentary

- CHAPTER 11: From Outline to First Script

- CHAPTER 12: Preproduction—Production Costs, Funding, Assembling the Crew, Compiling the Shot List, and On and On

- CHAPTER 13: The Art of the Interview and B-roll

- CHAPTER 14: Work Following the Interviews and B-roll

- CHAPTER 15: Choosing the Narrator and Other Voice Talent

- CHAPTER 16: Shot Making

- CHAPTER 17: Shooting Reenactments for Your Documentary

- CHAPTER 18: Using Still Photography, Historic Film Footage, Illustrations, Maps, Historic Newspapers, and Animation

- CHAPTER 19: Postproduction and Editing

- CHAPTER 20: Thoughts on the Beginning and the End of Your Documentary Film

- CHAPTER 21: The Digital Revolution and Its Role in Documentary Filmmaking

- CHAPTER 22: Television, Theatrical Release, Finding a Distributor, Self-Distribution, and Other Outlets

- CHAPTER 23: Promoting Your Documentary

- CHAPTER 24: Documentaries in Miniature

- CHAPTER 25: Creating Your Trailer

- CHAPTER 26: Conclusion

- APPENDIX 1: Sample Documentary Proposal

- APPENDIX 2: Documentary Treatment

- APPENDIX 3: The Lost Radeau Video Script

- APPENDIX 4: Simplified Sample Budget Outline

- GLOSSARY

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Documentary Filmmaking for Archaeologists by Peter J Pepe,Joseph W Zarzynski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.