eBook - ePub

Beyond Goals

Effective Strategies for Coaching and Mentoring

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

What is there in developmental relationships beyond setting and striving to achieve goals? The presence of goals in coaching and mentoring programs has gone largely unquestioned, yet evidence is growing that the standard prescription of SMART, challenging goals is not always appropriate - and even potentially dangerous - in the context of a complex and rapidly changing world. Beyond Goals advances standard goal-setting theory by bringing together cutting-edge perspectives from leaders in coaching and mentoring. From psychology to neuroscience, from chaos theory to social network theory, the contributors offer diverse and compelling insights into both the advantages and limitations of goal pursuit. The result is a more nuanced understanding of goals, with the possibility for practitioners to bring greater impact and sophistication to their client engagements. The implications of this reassessment are substantial for all those practicing as coaches and mentors, or managing coaching or mentoring initiatives in organizations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Beyond Goals by Susan David, David Clutterbuck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Didattica & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Goals: A Long-term View

The fascination with goals and goal achievement is deep rooted in human history. What is it that makes one person adhere year upon year, with tremendous energy, to a goal for themselves or for others, while other people with similar goals give up at the first hurdle? What is it about the power of a shared goal that encourages and sustains whole groups of people or even nations in tasks and activities that require great personal sacrifice? These are questions that have puzzled philosophers for millennia. Consider Aristotle who, over 2,000 years ago, proposed actions that individuals and communities could take in pursuit of goodness (Irwin and Fine, 1996).

In more recent history, these questions have increasingly preoccupied behavioral scientists and human resource professionals. The link between individual, team and organizational performance has become both clearer and more important as a differentiator in the success of businesses and other organizations (Pfeffer and Veiga, 1999). The study of goals tends to follow two paths: (1) goal setting—how and why people and organizations set goals in the first place, and (2) goal management—how goals are pursued (Locke and Latham, 1990; Locke and Latham, 2002; Riediger, Freund, and Baltes, 2005; Shah, 2005). In this first chapter we examine goals in history, and provide descriptions of the theories and research that have shaped the way we understand goal setting and goal management today.

What is a Goal?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a goal as “the object of a person’s ambition or effort; a destination; an aim” (Allen, 1991, p. 505). This definition explicitly conveys that a goal requires the application of physical or mental energy over a period of time. However, another definition is “a boundary or limit”. Indeed, this is the meaning of both the Old High German “zil”, and the Middle English “gol”, the root words for “goal” (Elliot and Fryer, 2008). This definition implies a very different set of concepts—among them that goals can be confining. It is an aspect that has not often been discussed, although, as we will see in the next chapter, the idea has been acknowledged by goal theorists and has recently come into greater prominence as a result of arguments between academics about the value of goal focus (Ordóñez et al., 2009).

A generally accepted academic definition of a goal is “a regulatory mechanism for monitoring, evaluating and adjusting one’s behaviour” (Locke and Latham, 2009, p. 19). This implies that goals are internal rather than external functions, although they may be focused on achieving change in a person’s environment and may be internally or externally motivated (Deci, 1975). Intrinsic (internal) and extrinsic (external) goal motivation are discussed further in Chapter 5.

Goal-addressed behaviors are fundamental to achievement in almost every aspect of human endeavor. Even infants recognize simple goal-oriented behaviors (Király et al., 2003), demonstrating that goal-related concepts take hold early in the human psyche. Just as we can trace goal orientation to initial stages of human development, we can recognize its existence in earlier periods of history. We consider this in the next section.

Goals in History

Over the centuries, people have found reasons to identify and pursue their ambitions. Dating back to antiquity, many religions have included a notion of a transcendent realm, or heaven, which has carried implications for human behavior (Ellwood and Alles, 2007). For example, in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, it is believed that people who have taken exceptionally good actions during their lives are reborn into heavenly realms. In Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and Islam people subscribe to a similar belief: those who are assessed favorably on the day of judgement will be granted entry to heaven.

In Western culture the belief in heaven as a reward for good behavior, bestowed in the after-life, was advanced by the Christian church and thus woven into the early social fabric. However, the Christian view of goals was complicated by the concept of grace, which has been defined as, “the unmerited favour of God; a divine saving and strengthening influence” (Allen, 1991, p. 511). Nonetheless, in the sixteenth century the Protestant reformation increased the importance of goal-directed behaviors: pursuing an occupation and excelling in worldly tasks was considered a demonstration of spiritual confidence, and evidence of one’s salvation (Wren and Bedeian, 2009). Fundamental to this approach was the notion that we cannot be complacent—we need to prove or improve ourselves. The existence of goals provided a future orientation. This helped people focus on what change was needed most, and to work diligently towards this.

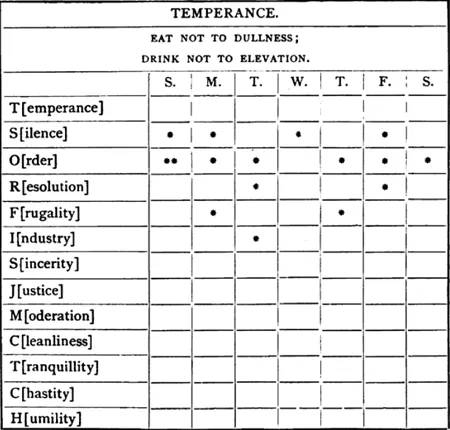

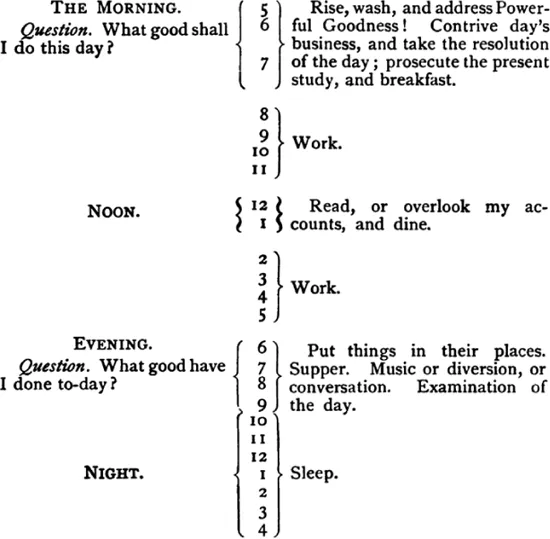

The Protestants’ industriousness continued to impact the worldview of many Westerners in the centuries that followed, including the founding fathers of the United States. Benjamin Franklin is famous for his Puritan-inspired work ethic and thirteen self-proclaimed virtues, which included resolution (doing as you intend), and industry (always engaging in something useful) (Franklin, 1791/1896). From Franklin’s autobiography, penned between 1771 and 1790, we know that he used a chart to monitor the virtuousness of his behavior, and that he kept a schedule of his daily activities. Franklin took advantage of the morning hours to reflect on his good intentions for the day, and he reviewed his accomplishments at night. His record-keeping offers a window into goal-directed behavior at the close of the eighteenth century (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

It was during this time that the Industrial Revolution was bringing sweeping changes to the way people lived and worked in a number of Western countries. The rise of the factory presented new challenges in organizing and coordinating goal-oriented behavior. The labor force consisted largely of those accustomed to farming, performing a trade in a small workshop, or helping their families. There were no established managerial practices or training regimes for factory life (Wren and Bedeian, 2009). The evolution of work life eventually brought management issues into the arena of science and academia, notably with Frederick Taylor’s work on scientific management (Taylor, 1911). This was complemented by the development of scientific psychology in Europe, spurred by Wundt’s pioneering laboratory experiments, as well as Freud’s investigation of the human psyche (Hergenhahn, 2009). Goal-related behavior became a topic of interest for scholars, who began to generate theory and research to enhance our understanding of goal setting and pursuit.

Figure 1.1 From Benjamin Franklin’s book of virtues

Source: Franklin, 1791/1896, p. 99

Figure 1.2 Benjamin Franklin’s daily schedule

Source: Franklin, 1791/1896, p. 101

Goal Theory, Research, and Practice

In this section we discuss the evolution of research on goals, in academia and in practice. Where appropriate, we link this research to key issues in coaching and mentoring. These topics are further explored in subsequent chapters.

The academic study of goals dates to the early 1900s, when psychologist Narziß Ach (1905/1951) began investigating volition and willpower at Germany’s Würzburg School. He argued that goal images led to the formation of conscious or unconscious determining tendencies, and these in turn prompted people to take action (Ach, 1905/1951, 1935; Elliot and Fryer, 2008). Kurt Lewin (1926/1961)—best known for his law that behavior is a function of the person and the environment—built on Ach’s work by studying the concept of intention. He went on to analyze forces that either helped or hindered people in their processes of goal pursuit.

The first known empirical research into goal setting was by Mace (1935), who also pioneered what we now call employee engagement. Mace showed that money was not the dominant work incentive, and maintained that people’s will to work depended on circumstances and work environment. His experiments into goal setting laid the foundations for Drucker’s (1954) Management by Objectives (MBO), and for the “giants” of goal theory, Edwin Locke and George Latham (1990), to eventually develop their theories and experiments.

MANAGEMENT BY OBJECTIVES

The technology of goal setting took a leap forward in the 1950s and 1960s with Peter Drucker’s (1954) development of Management by Objectives (MBO). Its driving principle is that defining and focusing on specific goals improves the efficiency of resource use. Drucker observed that managers became trapped in activity, spending most of their time on tasks that contributed little benefit to the organization’s overarching objectives. By focusing on fewer, more significant goals and ensuring that all employees were aware of both the overall goals and individual, specific goals, organizations could be more effective and productive. Clarifying goals thus became more important than controlling how employees achieved them, and negotiating individual goals played a significant part in gaining employee commitment.

The popularization of “stretch” goals has taken MBO theory a step further. A stretch goal is one that the pursuer does not know how to reach, and that may even seem unrealistic (Kerr and Landauer, 2004). The practice of setting stretch goals was popularized in the 1990s at General Electric by the former CEO, Jack Welch. Welch observed that in “reaching for the unattainable” (Krames, 2002, p. 46), people were able to achieve far more than they believed they could.

Today stretch goals continue to be frequent triggers for coaching and mentoring interventions. When faced with a difficult task, one that requires a change in thinking or new perspectives, individuals and teams can benefit from the rigorous processes that effective coaching entails. In particular, coaching and mentoring can help to counterbalance excessive optimism or unwillingness to consider failure—for example, by ensuring that resource issues are discussed.

Proponents of MBO see goal setting as helping organizations and individuals shift their attention from inputs to re-focus on outputs. This is viewed as a liberating process, providing individuals and teams the freedom to choose the means whereby they will achieve goals, and saving senior management from having to pay attention to the details of these means. Indeed, Drucker saw this as an emancipatory force in business (Drucker, 1954).

Many coaches and mentors today encounter busy leaders who are liberated when they step back from daily activity to reflect upon and prioritize tasks. Implicit in this stepping back is an opportunity to gain clarity on what is truly worth doing, and to focus energy on the important, rather than solely on the urgent. Goals make feasible the integration of the efforts of hundreds or indeed thousands of individuals, and so are inevitable and invaluable. With the growing complexity of the workplace, leaders are simply no longer able to master the details of individual jobs. They need to get hold of the outputs and to call for an account of progress towards achieving these. Following Drucker’s MBO, leaders can set targets even when they do not know how they are to be achieved.

MBO has been widely embraced in organizations; however, many objections have been raised over the years. Critics of modern management methods (e.g. Foucault, 1975; Brewis, 1996; Jacques, 1996) have regarded the shift toward defining objectives as enlarging the degree of control exercisable by the leaders of organizations, by enabling them to hold firmly onto the levers of change. They have suggested that individuals in contemporary organizations will find their lives regulated by a cascade of goals from those senior to them, and these will be used to focus employees’ efforts, measure their performance, and determine their financial and reputational rewards. These critics envision that goals will become the means by which a dominant group will exert power and “drive performance”—to use a common phrase in management discourse—in a non-dominant group. In this context, employees’ commitment to the economic objectives of the business enterprise is protected and made subservient to the potentially joyful act of work in and of itself (Foucault, 1975; Brewis, 1996; Jacques, 1996; Peltonen, 2012).

Johnson and Bröms (2000) have critiqued the mechanistic mind-set that is seen as being promoted through MBO’s goal orientation. Their research has demonstrated that targets set by the big three US automotive manufacturers had distorting effects on the flow of products through the manuafacturing process: the targets incentivized manufacturing divisions to produce and sales people to sell, regardless of the balance between supply and demand. Toyota, on the other hand, benefitted from having no targets beyond the call for continuous improvement, and with each car on the production line being manufactured in response to a specific order from a customer.

Johnson and Bröms have advocated for an approach that draws on the work of one of Drucker’s contemporaries, William Edwards Deming, who formulated a contrasting perspective to MBO. Deming’s leadership of the Quality Management movement is discussed in the next section.

DEMING AND THE QUALITY MANAGEMENT MOVEMENT

Deming began his work in Japan at the close of the 1940s, and later gained notoriety in the United States for his work at Ford Motor Company (Wren and Bedeian, 2009). Deming emphasized pride in work through continuous improvement, and freedom from the constraint of targets against which individuals and teams had to perform (Deming, 1986). The twelfth of Deming’s famous fourteen principles was to:

Remove barriers that rob the hourly worker of his right to pride of workmanship. The responsibility of supervisors must be changed from sheer numbers to quality.

Remove barriers that rob people in management and in engineering of their right to pride of workmanship. This means, inter alia, abolishment of the annual or merit rating and of management by objective. (Deming, 1986, p. 24)

Deming (1986) also pointed out that statistical understanding was necessary to measure work, and that an appreciation of statistics would demonstrate that individual performance is at the mercy of a wide range of factors outside of the worker’s control. Moreover, he maintained that the most important things could not be measured.

Drucker’s MBO and Deming’s Quality Management movement have offered contrasting theories and methodologies that have impacted the way organizations approach goals. Another important source of influence is the work of psychologists Edwin Locke and Gary Latham, who are responsible for generating what has become standard goal setting theory.

LOCKE AND LATHAM’S THEORY OF GOAL SETTING AND TASK PERFORMANCE

In the mid-1960s Locke began studying the relationship between goals and performance. Based on a review of goal setting literature, he concluded that more challenging goals were related to better performance (Locke, 1968). Latham subsequently helped to validate this claim by performing field studies with logging crews (Latham and Locke, 1975) and typists (Yukl and Latham, 1978). The positive relationship between goal difficulty and performance was replicated many times in laboratory settings (Locke et al., 1981).

Locke and Latham (1990, 2002) subsequently joined forces to generate goal setting theory. Building on Ryan’s (1970) work on con...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Editors

- Notes on Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Reviews of Beyond Goals

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Goals: A Long-term View

- 2 Goals in Coaching and Mentoring: The Current State of Play

- 3 Researching Goals in Coaching

- 4 New Perspectives on Goal Setting in Coaching Practice: An Integrated Model of Goal-focused Coaching

- 5 Self-determination Theory Within Coaching Contexts: Supporting Motives and Goals that Promote Optimal Functioning and Well-being

- 6 A Social Neuroscience Approach to Goal Setting for Coaches

- 7 Putting Goals to Work in Coaching: The Complexities of Implementation

- 8 The Coaching Engagement in the Twenty-first Century: New Paradigms for Complex Times

- 9 Goal Setting: A Chaos Theory of Careers Approach

- 10 When Goal Setting Helps and Hinders Sustained, Desired Change

- 11 The Goals Behind the Goals: Pursuing Adult Development in the Coaching Enterprise

- 12 GROW Grows Up: From Winning the Game to Pursuing Transpersonal Goals

- 13 Goals in Mentoring Relationships and Developmental Networks

- 14 Emergent Goals in Mentoring and Coaching

- 15 Goal Setting in a Layered Relationship Mentoring Model

- 16 Working With Emergent Goals: A Pragmatic Approach

- 17 The Way Forward: Perspectives from the Editors

- Index