- 119 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Essentials of Dyadic Interviewing

About this book

Traditional qualitative interviews typically involve a single subject; interviews of dyads rarely appear outside marketing research and family studies. Experienced qualitative researcher David Morgan's brief guide to dyadic interviewing provides readers with a road map to expand this technique to many other settings. In dyadic interviews, the interaction and co-constructions of the two subjects provide the data for the researcher. Showing the advantages and disadvantages of interviewing two people at once, the first book on this research topic -covers key issues of pair rapport, ethics, confidentiality, and dealing with sensitive topics;-describes the entire process from selecting the participants to the role of the moderator to analyzing results;-uses examples of grad student experiences, physician behavior, substance abuse, services to elderly, and dementia patients to show its many applications.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. Introducing Dyadic Interviews

The goal in dyadic interviews is to engage two participants in a conversation that provides the data for a research project. The broad outline for the content of such conversations—because they are interviews—is determined by the researcher's questions. At the same time, the goal is to provide the participants with a topic that will bring out their interest in what each other has to say. From the researcher's point of view, the conversations in dyadic interviews are the source of data, whereas from the participants' point of view these conversations are a chance to exchange ideas and experiences on a subject of mutual interest.

Traditionally, qualitative interviews have involved a single participant in one-to-one interviews or several participants in a focus group. There is thus an interesting gap in the size range, which does not include interviews that involve pairs of participants. Dyadic interviews fill that gap. However, given the naturalness of having two people talk to each other, it is not surprising that the equivalent of dyadic interviews has received some attention. In particular, two areas where such an equivalent has been used are marketing research and family studies. Within marketing research, focus groups have long been the dominant form of qualitative research (Greenbaum, 1998; Mariampolski, 2001). In this context, dyadic interviews are often referred to as mini- or microgroups. Greenbaum (1998) points to the value of dyadic interviews whenever the categories of participants come in natural pairs, such as partnered couples and buyers and sellers. Mariampolski (2001) highlights the use of dyadic interviews when recruiting the number of participants necessary for a focus group would be difficult or when a more in-depth discussion is preferred. Unfortunately, even though market researchers have promoted the potential value of dyadic interviews, there are very few examples of their use in this field.

By comparison, researchers in family studies (for example, Reczek, 2014) and related areas have made much more consistent use of dyadic interviews. The most obvious example in this field is the joint interview of partnered couples, although pairings of parents and children also occur. Similarly, there are studies that bring together pairs of friends and peers. In each of these cases, the defining characteristic is the use of preexisting relationships, whereby the research begins with an interest in some kind of naturally occurring dyad and then recruits sets of participants that satisfy this requirement. For present purposes, this approach amounts to a specialized form of dyadic interview, which is covered in Chapter 3. In contrast, rather than limiting dyadic interviews to preexisting relationships, this book uses a wider definition that includes the use of strangers who share an interest in a particular topic.

Dyadic Interviews in Practice

To illustrate the use of dyadic interviews, I rely on five examples of studies that have used this method (Morgan et al. 2013; Morgan et al., in press). The remainder of this introductory chapter summarizes each of these research projects.

The Experience of Early-Stage Dementia

Jutta Ataie studied people in the early stages of dementia to learn how their lives were changing after receiving this diagnosis. The primary interviewing technique that she used was photovoice (Wang & Burris, 1997), whereby the participants took photographs of the things that were important in their life and then discussed those pictures with the interviewer. Most of the data in the study consisted of individual interviews, but she also conducted a set of dyadic interviews that served in part as member checks (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) to learn the extent to which participants shared similar views with regard to her preliminary analyses.

Given both the special needs of this population and the sensitivity of the topic, Ataie chose dyadic interviews, which proved to be a good decision. In particular, pairing a participant with a similar person made it easier to create a sense of safety in exploring emotional issues. Further, participants' mutual understanding made it possible to overcome difficulties in communication and produce a lively conversation. As she noted, the participants "engaged in intense discussions that were characterized by sincere interest, respect, and curiosity, as well as a high level of interaction" (Morgan et al., 2013:1278). As the conversations progressed, the participants felt free to express diverging perspectives and even to disagree with each other, and this openness was quite useful in the member checking portion of the interview.

Providing Informal Services to Elderly Residents of Low-Income Housing

Paula Carder studied a variety of social service workers who came in contact with elderly residents of government supported, low-income apartments. Technically, these residents were required to be living independently, but many of them received at least some informal assistance from social service personnel. By definition, this support was not coordinated, and these interviews were often the first chance that the participants had to meet others who had potentially comparable experiences. Thus these interviews were exploratory for both participants and the researcher.

The heterogeneity in these interviews was especially interesting, because the participants had encountered related issues from a diverse range of perspectives. In this case, the rare opportunity to compare similar and different experiences was more than enough to create active conversations in which participants often questioned each other in ways that triggered new discussion topics. This situation led to the expression of what was unique about each perspective as well as a sense of what was shared across the different circumstances that arose from the participants' different jobs.

Substance Abuse among Asian and Pacific Islanders

Kim Hoffman (Morgan et al., 2013) interviewed Asian and Pacific Islanders who were substance abusers, and they arranged additional interviews with pairs of counselors who worked with them. One of her concerns was her outsider status as a white researcher, so bringing together participants with shared concerns made it easier for them to discuss this sensitive topic. Further, her use of snowball sampling meant that many of these participants were acquaintances, which made it easy for them to create joint accounts and fill in each other's stories.

The results were, however, rather different in the interviews with the substance abuse counselors. In this case, the conversations produced useful data, but they were less lively and free flowing than the interviews with their clients. One major reason for this hesitancy was that the work turned out to be a sensitive topic for these participants, but not because of privacy concerns. Instead, the issue was that these counselors were universally white and thus experienced their own outsider status. In addition, there was a sense that the researcher, as an educated professional in their field, may have been judging their work performance. There was thus a reversal, whereby the participants who were most different from the researcher were most at ease, whereas similarities in status may have created a barrier to full participation.

Telephone Interviews with Physicians Making Changes in Their Practices

Susan Eliot conducted a study that evaluated a program to support rural physicians who were in the process of switching to a computer-based electronic medical records (EMR) system. Because the participants were both extremely busy and widely dispersed, she conducted the dyadic interviews by telephone. In choosing how to create the pairings, she wanted to have enough heterogeneity for the participants to compare their experiences, especially those who had more and those who had less experience with the EMR system. Throughout the study, she had assistance from a central member of the program itself, who served as a key informant with regard to issues such as which doctors would make good conversation partners, given that most of them were at least somewhat acquainted.

The most obvious implication for dyadic interviews was the success in conducting them by telephone. Because the study also included earlier rounds of individual telephone interviews with the same physicians, Eliot could draw conclusions about the similarities and differences between the two situations. Although the range of substantive topics was very similar, the dynamics of the interviews were quite different: the extended conversations in the dyadic interviews produced both more in-depth and broader data. In particular, the physicians were very interested in exploring each other's experiences with the sometimes difficult transition to EMR systems. This shared interest made it easy for the moderator to allow each interview to progress on its own terms, since the participants stayed on topic and required very little active prompting or probing.

Dyadic Interviews and Focus Groups with First Year Graduate Students

In my own work, I have done both dyadic interviews and focus groups with first-year graduate students, to hear about the experiences of becoming a graduate student. In both cases, the recruitment criteria specified that each participant should be from a different department or program. This requirement created a degree of difference between the participants and generated an interest in discovering what things they had in common and what was distinct. The result was a set of lively interviews in which the participants engaged in a great deal of "sharing and comparing" as they explored what had happened in the year since they entered graduate school. (See Appendix B for a complete transcript of a dyadic interview from this research project.)

Comparing the focus groups and the dyadic interviews showed that they both produced similar content, with the same topics appearing in each and receiving similar emphasis. Where the difference occurred was in the dynamics of the interaction. In the focus groups, each turn at talk tended to be longer and more self-contained, whereas the exchanges in the dyadic interviews were more rapid and intertwined. Note that these were typical examples of each format, rather than particularly "slow" focus groups or especially "energetic" dyadic interviews. Rather, these seem to be characteristic differences between group discussions and pairwise conversations.

2. Positioning Dyadic Interviews

Dyadic interviews have existed for some time under one label or another, including joint, peer, paired, an two-person interviews. Regardless of label, interviewing two people through their shared conversation is a general method that can be used for a wide range of purposes in qualitative research. This means that in many situations there will be a choice about when to use dyadic interviews as opposed to either individual interviews or focus groups. Often, all three forms of interviewing will provide a viable option, so the interviewer needs to have a sense of the specific advantages and disadvantages associated with dyadic interviewing. Hence, this chapter provides systematic comparisons of dyadic interviews with individual interviews and focus groups, respectively.

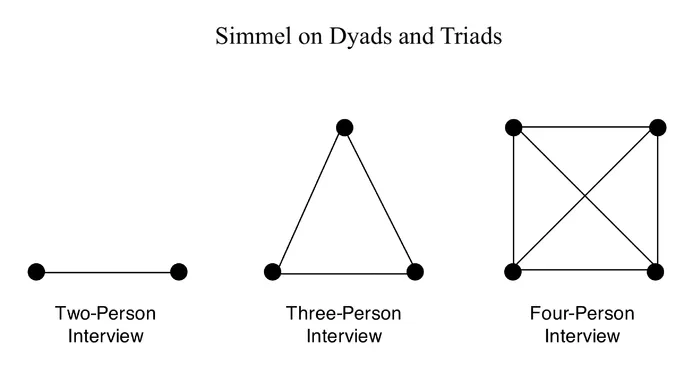

Before considering the comparison to either individual interviews or focus groups, we need to consider one other issue. The literature on focus groups typically treats four as the smallest number of participants, which means that three-person, or triadic, interviews have received just as little attention as dyadic interviews. This raises the question: why concentrate on just dyadic interviews? One obvious reason is that the classic idea of a conversation between two people is unique to dyads. Another reason is that the complexity of the interaction in groups rises rapidly with size. This complexity was famously discussed by Georg Simmel in his essay on the dyad and the triad.

As the figure on the next page shows, the two people in a dyad form a single, direct connection. By comparison, a triadic interview involves three connections between the participants. In addition, it introduces the possibility of indirect connections, whereby what one person says to another must also take into account what the third person might think. The figure also shows the increasing complexity that accompanies larger sizes. The move up to four participants creates six possible connections. From this perspective, the interaction patterns among four participants do indeed look like focus groups, whereas the two-person interaction in dyadic interviews is clearly quite different. Whether triadic interviews also have something distinctive to offer remains an open question that is addressed in the final chapter on future directions.

Comparisons to Individual Interviews

The most obvious difference between dyadic and individual interviews is interaction. Of course, individual interviews involve interaction between the researcher and the participant, but this part of the process is not typically taken as part of the data itself. In contrast, the interaction between the participants in dyadic interviews is what produces the data. This fact points to the importance of the interviewers role in both methods. In each case, it is the interviewer's job to ask the questions that determine the content of the interview, while taking either a more or less active part in directing the interview. In a one-to-one interview, the researchers job is to make sure the participant provides useful data, whereas in a dyadic interview the goal is to get the pair of participants to converse in ways that generate useful data.

The difference in the interactive dynamics of these two kinds of interview is reflected in the concept of rapport (Rubin & Rubin, 2011). For individual interviews a feeling of rapport needs to be established between the interviewer and the participant, so that the participant feels comfortable talking about the research topic. In contrast, it is the rapport between the two participants that is crucial in dyadic interviews. It is still the researcher's job to do everything possible to establish this pairwise rapport, but that is a different task from working directly with one research participant at a time.

The issue of the dynamics between the interviewer and the participant(s), along with the dynamics between the participants in a dyadic interview, is also related to the topic of self-disclosure of sensitive topics. In individual interviews, the nature of the disclosure is directly to the interviewer, whereas dyadic interviews include the additional dimension of what the participants share with each other. Although there is no systematic research on whether individual or dyadic interviews would be a better match for topics that require self-disclosure, the literature on focus groups suggests that there are situations in which the chance to talk to similar others is especially effective in this regard.

For dyadic interviews, talking to similar others highlights the case in which a pair of people share a comparable background with regard to the sensitive topic in question, which allows them to understand each other's experiences in ways that an outsider might not. Examples of this situation from the introductory chapter include the studies on drug abuse among Asian and Pacific Islanders and on earlier stages of dementia, both of which involve experiences that require exchange of potentially discrediting self-disclosures. The opportunity to talk to someone who comes from an equivalent background can make it much easier to negotiate barriers involved in self-disclosure.

Interestingly, dyadic interviews may carry as much risk with regard to telling too much as too little. In particular, the participants in a dyadic interview may be encouraged to higher levels of self-disclosure by the rare opportunity to talk to someone who genuinely understands their circumstances. The extent to which the participants in a dyadic interview share something in common about the topic is the key factor, rather than any fundamental difference between individual and two-person interviews. Researchers thus need to move beyond the assumption that talking to another participant requires an additional level of disclosure, to a recognition that they may be just as likely to encounter over-disclosure

A separate category of differences between individual and dyadic interviews arises from the amount of time that two people share in a dyadic interview. When two people participate in a one-hour interview, the amount of information from each of them is essentially half of what would have been available through an individual interview of the same length. This means that dyadic interviews provide less depth and detail on each participant than a set of comparable individual interviews. The trade-off is that the interaction in dyadic information can elicit a process of sharing and comparing that engages the participants in discussing their similarities and differences; this process is discussed at more length in the chapter on interaction. For now, it is useful to point out that the greater range of topics explored in dyadic interviews can be an advantage that offsets the reduced levels of depth and detail obtained for each person.

Both the shorter amount of time available per participant and the nature of the interaction indicate that there are also likely to be differences in the kinds of narratives that are available from individual and dyadic interviews. In addition to the potential for longer, continuous sections of narrative, individual interviews provide the interviewer more ways to probe, either to extend a given line of narrative or to move things in a different direction. Alternatively, dyadic interviews are more likely to generate a dynamic whereby the participants "co-construct" a joint narrative. In this case,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Chapter 1: Introducing Dyadic Interview

- Chapter 2: Positioning Dyadic Interviews

- Chapter 3: Relationship-Based Dyads

- Chapter 4: Ethical Issues

- Chapter 5: Interaction as the Foundation for Dyadic Interviews

- Chapter 6: Pair Composition in Dyadic Interviews

- Chapter 7: Writing Questions for Dyadic Interviews

- Chapter 8: Moderating Dyadic Interviews

- Chapter 9: Analyzing Dyadic Interviews

- Chapter 10: Conclusions

- Appendix A: Sample Interview Guide

- Appendix B: Sample Interview Transcript

- References

- Index

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Essentials of Dyadic Interviewing by David L Morgan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Research & Methodology in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.