![]()

Part I

The Music Business and Its Components

![]()

Chapter 1

The Record Industry and Record Distribution: Mapping the Territory

Our first chapter is designed to give the reader a concept of exactly how record companies function. Two chapters later there is a chapter on the DIY (Do It Yourself) movement, which for many artists has entirely re-shaped the way prospective artists pursue their careers. Despite these relatively new models and career choices, the fact remains that the remaining three major record labels, Sony, Universal and Warner Brothers, together with their various subsidiaries, still sell the lion’s share of recorded music throughout the world in digital or physical formats.

A Brief History of Recording

The history of the record industry can be told through the evolution of new technologies (recording formats), the growth of the record business (record labels), or through changing musical styles. Each tells us something about how the overall music business has grown and changed from the late nineteenth century to the early twenty-first century. The interplay between these three trends created the music industry as we know it today.

Early Years: 1870–1950

The record industry owes its origins to the experiments of several French scientists. In the nineteenth century, the French inventor Charles Cros designed, but did not actually build, a device that could record sound. It wasn’t until 1877 that the American inventor Thomas Edison developed an early version of the phonograph. Edison’s original vision of the machine did not include musical uses. He had a sort of Dictaphone machine in mind, which would be a valuable office tool. Edison’s machines recorded on wax cylinders, resembling solid mailing tubes. Soon prerecorded cylinders were being manufactured to play back on Edison’s phonographs.

Edison was not alone in these early experiments, and many others tried to improve on his invention. Notably, Chichester Bell, a cousin of Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, came up with a better way of recording onto wax cylinders. For several years Bell and Edison battled in courts over who owned the rights to this technology. Edison stubbornly refused to pay Bell, and launched his own Edison label to market his cylinders. Bell’s patent eventually formed the basis for the second major recording company, the Columbia Phonograph Company.

A major advance in recording technology was made by a German-born engineer named Emile Berliner, who experimented in the 1880s with a disc-based phonograph. It would eventually replace the cylinder-based machines at the turn of the century. In 1891 Berliner formed a company to market his new flat discs, which eventually became the Victor Talking Machine Company, the third of the original recording companies.

After the disc format took over from cylinders around the first decade of the twentieth century, Victor and Columbia shared the rights to the “lateral-cut” method of producing discs. These discs featured grooves on which the phonograph’s needle moved up and down on a layered (and thicker) disc. No other labels could compete until around 1920, when the original patents were beginning to expire. A proliferation of smaller labels blossomed in the 1920s through the early 1930s, when a combination of free music offered by radio and the Great Depression led to a collapse of the record industry. Edison shut down his record business in the early 1920s, and Victor was absorbed by the radio maker RCA. Columbia struggled on through various owners, eventually falling into the hands of the CBS radio broadcasting company in 1948. One new label, Decca Records, emerged as a major player in the early 1930s, thanks to signing singing star Bing Crosby.

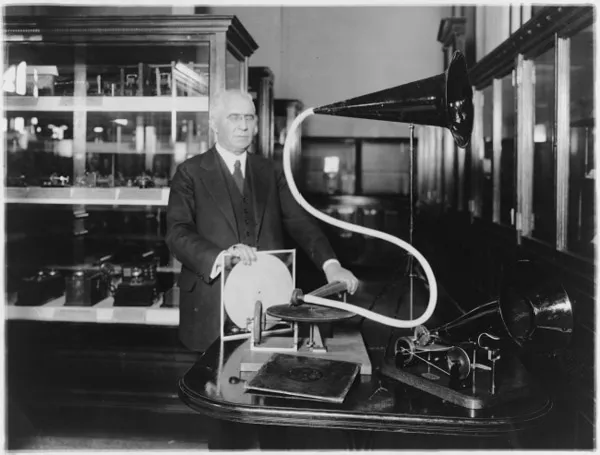

Emile Berliner holding an early flat disc record and standing next to a model of his first phonograph. (National Photo Company Collection, Library of Congress)

The standard recording disc of this era was played back at 78 revolutions per minute (RPM), often referred to as 78s. These discs were heavy but not terribly durable. Early sound recording technologies relied on acoustic recordings made through large horns, and were noisy at best. The introduction of electric microphones in the mid-1920s helped somewhat, but records were still easily broken and would wear out from repeated playback. Radio was introduced in the early 1920s, and it offered superior sound quality and limitless hours of music. The only cost was the purchase price of the radio itself, so that an initial investment yielded years of entertainment. By the 1930s many radio stations featured live music played by combos or orchestras. Phonograph records could not compete.

After World War Two, a new recording format led to a rebirth of the record industry. Columbia pioneered a long-playing (LP) disc that played back at 33 1/3 RPM. It offered both more playing time and better fidelity than the earlier 78s. RCA Victor responded with a 45 RPM “single” that was more economical to produce than earlier 78s. The new materials used to make these discs were less prone to breaking than earlier 78s. The LP became the preferred medium for adult listeners, who could enjoy longer works, such as Broadway musicals or classical symphonies. The 45 RPM single was pitched at the youth market, and it would soon become the medium for a new musical style: rock and roll.

The Rise of the Independents

During the first fifty or so years of the recording industry, the business was initially dominated by Edison, and then by Columbia and Victor, which held the crucial patents for making phonograph discs.

Smaller labels began to develop in the mid-1920s, after the patents expired. Smaller labels often catered to special markets, such as country or blues music. Many of these labels were eventually absorbed by the larger outfits, or went out of business. By the end of the 1930s Victor, Decca, and Columbia were the major players in the market.

From the 1930s through the early 1950s, American popular music primarily came from Broadway and Hollywood, and the major labels focused on these most popular forms. The majors also produced music for the smaller country and blues audiences, but in many cases they distributed this product on a regional basis, rather than a national one. Jazz was somewhat different, because it sometimes crossed over into popular music, especially when the band had a singer as a featured vocalist. Many of the popular music stars of the 1940s and 1950s, including Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee, and Jo Stafford, got their start singing with big bands before going on to become hit recordings artists. The genre of popular music before rock was introduced became known as middle of the road (MOR) music. This term has come to mean easy listening music designed to appeal to a broad segment of the audience for music, especially older adults.

Table 1.1 Major Recording Formats, c. 1880–Today Format | First Producer | Period of Popularity |

Cylinder | Edison | c. 1890–1910 |

78 RPM discs | Berliner (Victor) | c. 1910–1950 |

Long-playing (LP) records (33 1/3 RPM) | Columbia | c. 1950–1990 |

Singles (45 RPM) | Victor | c. 1950–1990 |

Cassette tapes | Phillips | c. 1970–1985 |

Compact discs | Phillips/Sony | c. 1985–ongoing |

MP3 | Protocol for file compression developed by an international group of producers | c. 1995–ongoing |

Antique phonograph. (a40757 / Shutterstock)

The growth of a West Coast-based music industry that fed motion picture production led many promising songwriters to settle in Hollywood, including Johnny Mercer, along with many talented musicians who were employed writing or playing film scores. Mercer then partnered with several others to form a new label, Capitol Records, in 1942, which tapped into this growing talent pool.

However, the postwar years would see new musical styles arise that the major labels were slow to recognize or record. This provided an opening for independent producers and small record labels from all around the country to enter the music business. In the early 1940s, rhythm and blues artists like Louis Jordan started to cross over into the pop marketplace. Their audiences spread beyond the African-American population where their music originated to different racial and economic groups. By the mid-1950s, rock and roll had begun to infiltrate America’s musical landscape, and middle of the road popular music began to be replaced by rock recordings. Because many of the A&R (artist and repertoire) executives at the major labels were middle aged and had come out of either a jazz or pop background, they had little interest or enthusiasm for rock and roll. This led to the almost meteoric rise of independent record labels.

Table 1.2 Independent Labels of the 1940s and 1950s Label | Founding Year | Home Base | Some Major Artists |

ABC Records | 1955 | Hollywood | The Impressions, Three Dog Night |

Atlantic Records | 1947 | New York City | Ruth Brown, Ray Charles |

Chess Records | 1947 | Chicago | Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry |

Duke and Peacock Records | 1952 | New Orleans | Bobby Blue Bland |

King Records | 1944 | Cincinnati | James Brown |

Mercury Records | 1945 | Chicago | Patti Page |

MGM Records | 1946 | Hollywood | Connie Francis, Hank Williams |

Motown Records | 1959 | Detroit | The Supremes, Smoky Robinson & The Miracles |

Stax Records | 1957 | Memphis | Sam & Dave, Otis Redding |

Sun Records | 1952 | Memphis | Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley |

United Artist Records | 1952 | Hollywood | Sound Track Albums, Little Anthony & the Imperials |

Warner Bros. Records | 1958 | Hollywood | Peter, Paul & Mary |

The independent labels operated in a very different way from the major labels. At the major labels, decisions were often made by committee, with sales, promotion, and A&R staff all listening to prospective artists before agreeing to sign them. The independent labels were run on shoestring budgets and often made decisions based on gut feeling rather than on a disciplined approach to the bottom line. They signed artists quickly and promoted their records in a freewheeling style that often included bribing disc jockeys or radio station program directors with cash, expensive gifts, or even participation in songwriting or publishing rights (see later in this chapter). The changing of the music business was best represented by the success of Sun Records, from Memphis, Tennessee. Operating out of a closet-sized studio with a tiny budget, Sun was able to successfully launch the 1950s best-selling artist, Elvis Presley, without any major label support. Elvis was so successful in his first years of recording that Sun was able to sell his contract to industry leader RCA Victor for $30,000, a stunning sum in those days. In later years independent labels have sold for sums in the hundreds of millions and even more.

In the 1950s, the major labels often didn’t understand the new music that young people liked, and they had no notion of how traditional song structures and written musical arrangements fit into the new idioms of rock and roll. But by the mid-1960s, the major labels had all joined the rock and roll parade. Newer and younger personnel moved the companies into the world of contemporary pop music, the artist roster of the major labels changed, and European record companies and artists became worldwide competitors for American record labels and artists. The European influence—particularly from Great Britain—was greatest in the mid-1960s when the Beatles and other British Invasion groups conquered the pop charts.

Victor 78 RPM record label from the late 1920s. (Recorded Sound Section, Library of Congress)

By then, Capitol Records was owned by the British company EMI (Electrical Musical Industries), which subsequently acquired the Liberty, United Artists, and Virgin labels, among many others. Similarly, German-based electronics maker Siemens and Dutch-based Phillips combined their label holdings in 1962, creating Polygram Records, which in turn bought Mercury, MGM, and Decca, and then acquired Island Records as well.

American-based companies followed suit in merging into larger conglomerates. Warner Brothers bought Frank Sinatra’s label Reprise, and more importantly it acquired Atlantic in 1967, Elektra in 1970, and Asylum (David Geffen’s label) in 1972. There were a number of reasons for these acquisitions. On the one hand, the larger companies saw new opportunities by acquiring producers and artists who seemed to understand musical styles that were a bit of a mystery to the majors. The independent labels, like Island, Atlantic, or Elektra, were often founded by a single owner or a small group of owners who were doing quite well but were always cash poor because their profits went back into the business. By selling to a major label, these individual entrepreneurs acquired better financing and distribution for their labels, and also suddenly became wealthy. In some cases the founders stayed with the companies for years after selling their ownership stakes in the companies. Columbia Records grew in a different way by acquiring related entertainment businesses, including Fender Guitars, Steinway Pianos, and the New York Yankees baseball team.

The story since then has been one of continuing consolidation in the recording industry. In 1986, the German publishing company Bertelsmann bought RCA, and a year later Japanese electronics giant Sony purchased Columbia Records. Sony and BMG then entered into a joint operating agreement for their labels in 2004. The Japanese company Matushita bought MCA, then sold it to Canadian liquor company Seagram, which in turn was bought by the French engineering and sewage company Vivendi. This left Warner Brothers as the only American-owned label. Vivendi’s record division is named Universal, and besides owning Decca, ABC, and MCA, they also own rap record labels Interscope and Def Jam. In 2008 Sony bought BMG’s music holdings, including RCA. In 2011 Universal added EMI to their portfolio, reducing the number of major labels to a mere three: Sony, Universal, and Warner Brothers.

How Major and Independent Labels Are Organized: Business and Creative Functions

Major labels have branche...