- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Shaping World History

About this book

This innovative survey of world history from earliest times to the present focuses on the role of four factors in the development of humankind: climate, communication and transportation technology, scientific advances, and the competence of political elites. Matossian moves chronologically through fifteen historic periods showing how one or more of the causative factors led to significant breakthroughs in human history. Shaping World History is based on original research and also draws widely from the literature on the history of science, technology, climate, agriculture, and historical epidemiology. This compelling analysis is presented in a personal style and includes reflections on how things work and why they are important.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Shaping World History by Mary Kilbourne Matossian in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | FROM HOMINIDS TO HUMAN BEINGS |

Biology, Geography, and Climatic Change

Man is an exception, whatever else he is. If it is not true that a divine being fell, then we only say that one of the animals went entirely off its head.

—G.K. Chesterton

Anthropologists have named us Homo sapiens sapiens, the clever, clever hominid. Over a century ago certain scientists abandoned the Western creation myth and began to seek human origins in nature among the primates (apes and monkeys). If apes and people had many resemblances, what kind of creatures linked the two species? When and where did this linking happen?

The discoveries of physical anthropologists and geneticists have indeed established that we belong to the primate family. The line of hominids (bipedal apes, apes who walk on two legs) differentiated from that of other apes about five million years ago. We share with chimpanzees and bonabos (pygmy chimpanzees) between 98 percent and 99 percent of our structural genes. Who can watch primates in a zoo without experiencing a shock of recognition?

In December 1992 in Ethiopia, Tim White, an anthropologist from the University of California at Berkeley, and his team discovered the earliest hominid yet known. They announced their discovery in September 1994. Anthropologists believe that the bones discovered are almost 4.5 million years old. These hominids walked upright, were four feet tall, and lived in a woodland setting. Their skull capacity was about one third that of ours.1 They lived very close to the time of separation between hominids and apes estimated by geneticists—five million years ago.

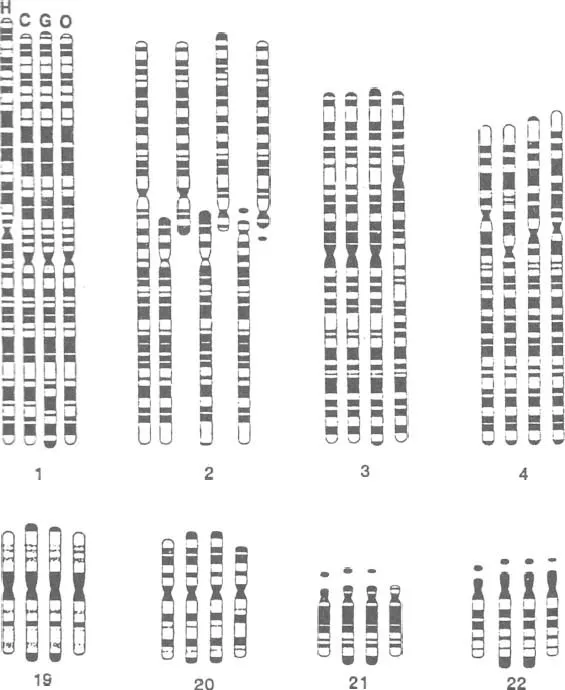

Figure 1. Schematic representation of late-prophase chromosomes (1000-band stage) of man, chimpanzee, gorilla, and orangutan, arranged from left to right, samples 1–4 and 19–22, visualizing homology between the chromosomes of the great apes and humans. (Reprinted with permission from J.J. Yunis and O. Prakash, “The Origin of Man: A Chromosomal Pictorial Legacy,” Science 215 [March 19, 1982], p. 1527. © 1982 by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

In August 1995 Maeve Leakey and her team discovered in Kenya similar hominids that were 4.1 million years old. These hominids are estimated to have weighed between 101 and 121 pounds.2 This is the most recent of a long sequence of discoveries. It now seems likely that hominids differentiated from apes in northeast Africa, in or near the Great Rift Valley of Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania. Hominids had habitually upright posture and walked on two legs. They lived mainly on the ground, not in trees. These attributes appeared long before their brain expanded and they began to make tools.

About fifteen million years ago the environment in East Africa was changing. The earth’s crust was splitting apart in places, while highland domes of up to nine thousand feet formed in Ethiopia and Kenya. These domes blocked the west-to-east airflow and threw the land to the east into rain shadow. Lacking moisture, the continuous forests in the east fragmented into patches of forest, woodland and shrubland. About twelve million years ago the Great Rift Valley, running north to south, appeared in East Africa.

This development had two major biological consequences. First, the Great Rift Valley was an east-west barrier to the migration of animal populations. Second, although the apes in the dense jungle on the west side of the valley were already adapted to a humid climate and thus were not forced to adjust to a new environment, in the east a rich mosaic of ecological conditions emerged. Biologists believe that mosaic environments drive evolutionary innovation, since competing successfully in such an environment requires new adaptations. The hominids—bipedal apes—developed in such a place. This is the first example of the influence of climatic change on prehistory.

According to Peter Rodman and Henry McHenry, on the east side of the Great Rift Valley, where woodlands were scattered, a bipedal ape had an advantage. It could move more easily from one grove of food-bearing trees to a more distant grove. An ape who walked habitually on two legs was more energy-efficient than an ape who walked on four. Upright posture was also more efficient for cooling the body in the daytime heat. Other anatomical changes made it easier for hominids to stride and to run. The beginning of brain expansion in hominids began in Africa around 2.5 million years ago with Homo habilis and was associated with the appearance of the earliest stone tools. By 1.8 million years ago a more advanced hominid, Homo erectus, was making sharp-edged tools. The process involved knocking one rock against another, chipping off a sharp flake from the “core” stone and using the flake as a knife. Hominids could use this knife to cut through the hides of most animals and get to the meat quickly. Evidence shows that with this innovation hominid meat eating soon increased.

There was probably a positive feedback loop between the expansion of the hominid brain and meat eating. The hominid brain is three times as big as that of an ape of similar body size. Meat is an excellent source of protein and, because of its fat content, is high in calories; this helps to support the larger brain. At the same time the growth of the brain in relation to body weight favored the improvement of human hunting skills and higher meat consumption. In hominid females, the pelvic opening widened to compensate for the increased brain size of the hominid infant. However, that was not enough, and any greater widening would reduce bipedal mobility. A solution to the problem of increased hominid brain size was the natural selection of those hominids that produced children born “too early,” with brain size only one third that of an adult. These infants are slow to mature and so depend on their parents for a longer period. This extends the time that parents can transmit culture (patterns of behavior) to their offspring. In contrast, baby apes are born with a brain one half the size of that of an adult ape. They mature more quickly than hominids do, but have fewer years of dependency to learn from their parents.

What sort of culture did prehistoric humans transmit? Cultural anthropologists who have studied the way of life of foragers (hunter-gatherers) today say that the usual size of a human band is twenty-five persons, including children and adults. A larger unit, the dialectical tribe, includes about five hundred persons. Foragers use only temporary camps and move about on their range. Since longevity was usually only twenty-five to thirty years, many children were raised by relatives, their parents being dead. The band, not the nuclear family, was the principal social unit.3 A band acquires food cooperatively, by hunting and gathering, and shares it. Adults teach their children, who are born self-centered, to become sensitive to the needs of others and to share food.

Is such sharing, social behavior unique to humans? Frans de Waal, a researcher at the Yerkes Primate Research Center in Atlanta, Georgia, discovered that chimpanzee groups consist of caring, sharing individuals who form self-policing networks. He believes that the roots of morality may be far older than we are. A chimpanzee seems to realize that social disorder is a threat to its individual well-being. When rivals embrace, signaling an end to their fight, the whole colony may break into loud, joyous celebration.

However, chimpanzees share food and other treasures only when it is to their advantage. They cheat when they can get away with it by hiding a private stock of food. When cheating, they try to deceive other members of the group. Fortunately, they live in groups of less than a hundred, so they can watch each other and identify the cheaters. Older chimpanzees deny food to young cheaters by excluding them from sharing in the next windfall.4

It appears that both our moral and immoral tendencies are part of the natural order. Both “good” and “evil” are aspects of our adaptive and competitive strategies. We can imagine that human goodness developed out of the need to adjust to a cooperative group. By belonging to such a group an individual had a major advantage in the struggle to survive and reproduce.

No more can we think of stone-tool making and sharing behavior as unique to our species. Nor are we unique in our capacity for tactical deception and savagery. Rather, we have a place in a natural mammalian continuum.

The only behavior unique to humans appears to be the ability to communicate quickly with a large number of phonemes (discrete sounds). We can make fifty phonemes; apes can make only twelve. Humans can speak more quickly and articulately than any other species. The placement of our vocal organs makes this possible.

When did our ancestors acquire spoken language involving more than twelve phonemes? Some anthropologists think it was as far back as 2.5 million years ago (the time of Homo habilis). Most agree that complex spoken language goes back at least thirty-five thousand years to the time of the cave paintings in Europe. They think that language evolved as a means of social interaction, allowing individuals to prevent fights or settle them more easily.5

Recent discoveries in the Pavlov Hills of the Czech Republic indicate that ceramics and weaving go back twenty-seven thousand years—to before the beginning of settled life. These skills were probably the innovations of women, because women could make pots and weave while they took care of children.6

When did people exactly like us, anatomically speaking, appear? Many anthropologists think that our species (Homo sapiens sapiens) differentiated around two hundred thousand years ago in either south or northeast Africa. From northeast Africa people spread across the earth. They went to the Near East, Europe, China, Southeast Asia, Australia, the Pacific Islands, and the Americas.

Lucky humans settled on lands suited to agriculture. Only they could look forward to sustained population growth and civilization. They were especially lucky if the relationship between land and water in their region was favorable for water transportation, as the cost of moving bulk goods by water for a given distance was one eighth to one twentieth that of moving them by land. Waterborne commerce may have been just as fundamental as the development of farming for the birth of civilization.

Geography and Prehistory

Given limited prehistoric shipbuilding skills, the tamer the water the better. Navigable rivers that did not dry up in the summer were important in moving goods from the interior of continents to settlements on the shores of lakes, inland seas, and oceans. Primitive sailors, without navigational instruments, preferred coastlines with well-marked natural features and deep harbors. The Mediterranean Sea, a tideless inland sea with stepping-stone islands, was a magnet. Seas and oceans with predictable winds and currents, such as those of the northern Indian Ocean, were more attractive than rough and capricious waters, such as those of the North Atlantic.

Eurasia had great geographical advantages. It included a variety of environments, animals, and plants. Its long east-west belt of fertile soil and temperate climate made it highly suitable for food production and exchange. Certain parts of Eurasia had particular advantages. The Middle East was centrally located, controlling east-west trade routes. It included territory such as the Suez Isthmus and the easily navigable extensions of the Indian Ocean: the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Persian Gulf. The alluvial valleys of the Nile, Tigris-Euphrates, and Indus Rivers had rich soil that could support a dense population.

China had two great rivers, the Yellow and the Yangzi, which could be linked by canals. It had great botanical diversity to draw upon for food. But unlike Europe, it did not have an inland sea. Much of the Yellow River was not navigable and frequently flooded. The rocky north and central Chinese coast lacked good harbors. These factors constrained the commercial development of China.

Northern and western Europe were blessed with many navigable rivers linking the interior with the coasts. Water and land interpenetrated: Europe was a peninsula of peninsulas. The North, Baltic, Black, and Mediterranean Seas moderated the climate and served the needs of waterborne commerce. Europe had long coastlines and many harbors. It had 4 kilometers of coast per 1,000 square kilometers of land, while Asia had only 1.7 square kilometers of coast per 1,000 square kilometers of land. This too was an asset for traders.

From a global perspective, most of the water surrounding Europe, even the Mediterranean Sea, was cold. This meant that shipbuilders could use iron nails to fasten together the parts of a ship without fear of early rusting and wood decay. Nailed ships were structurally fit to sail in rough waters. On the other hand, South and East Asia were surrounded by warm water, in which nails quickly rusted and wooden structures accordingly decayed. The boats sailing in these waters were most often held together by fiber ropes—coconut, hemp, etc. Such ships were not sturdy enough to sail in rough waters over long distances.

From a human point of view the Americas, Africa, and Australia were disadvantaged continents. None had an inland s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction: Major Causes of Breakthroughs

- 1. From Hominids to Human Beings: Biology, Geography, and Climatic Change

- 2. The First Farmers

- 3. The Birth of “Civilization,” 4000 to 500 B.C.

- 4. The Roman Empire and the Han Empire, 200 B.C. to A.D. 200

- 5. The Chinese Millennium, A.D. 500 to 1500

- 6. Reasoned Dissent: Printing, Universities, and Transport

- 7. Protestant Maritime Political Culture: The Breakthrough to Freedom

- 8. The Scientific Revolution of the Seventeenth Century

- 9. The Population Explosion, 1700 to 1900

- 10. The Industrial Revolution in Britain

- 11. Social Control Since 1789

- 12. Darwin’s Dangerous Idea

- 13. The Marriage of Science and Technology

- 14. Breakthroughs in Science, 1895 to 1997

- 15. The Third Communication Revolution

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index