![]()

| CHAPTER 1 |

INTRODUCTION |

COMMODITY BRANDING IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND ANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES |

David Wengrow

The origins of this book lie in coincidence. About 5 years ago I was reading Naomi Klein’s No Logo (2000), with no special academic interest in the world of branding. At much the same time, I was teaching graduate classes at UCL’s Institute of Archaeology, some of which dealt with the early development of writing, pictorial art, and urban economies in the Middle East. UCL itself was about to undergo an expensive and controversial rebranding exercise. A new university logo was presented to staff, and instructions were provided on how to deploy it, what it represented, and how this was to be reflected in our professional lives and public conduct. My response to this set of circumstances eventually came together in an article (“Prehistories of Commodity Branding”) published in 2008 in Current Anthropology, together with comments—some very favourable, others highly critical—from an unusual combination of scholars in archaeology, anthropology, art history, and marketing. Its main argument, which I summarise below, was (in brief) that something we would recognise today as commodity branding can be found in much older societies, including those of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, where the first cities and large-scale economies emerged around 6,000 years ago.

Within months of its publication, the findings of the article had been reported in a number of major media outlets, such as The Telegraph and New Scientist. I gave a live radio interview about the origins of branding and for a short time was contacted on an almost daily basis by journalists wanting to write about branding in the ancient world. Summaries of the article, many of which exaggerated and/or oversimplified its claims, began to appear in consumer blogs based in such diverse places as India and Poland. A leading business think-tank invited me to a closed debate on the future of global branding, hosted by a well-known TV pundit, where I found myself a lone archaeologist in the company of CEOs from Interbrand and Coca-Cola. Although this was all quite flattering, and fully in line with the new brand image of my university, it was also confusing. I had not, contrary to what some people wrote or said, made any great new “discovery” (a number of my interviewers were disappointed when I explained that I could not provide them with an image of “the ancient brand” I had found). Rather, I had simply interpreted information that is quite familiar in my field in a new way. So, why the fuss?

The reason seemed quite clear, but also problematic. Most people are aware of and talk about commodity branding on the assumption that it is the product of modern capitalist markets, and that we therefore know quite intuitively what it involves. Of course, there are marketing experts and brand gurus, some of whom I have now met, who know far more about how it works than others, but it has generally been assumed that we, as consumers of brands, and they, as designers of brands, are all talking about roughly the same thing. It is also clear that capitalist logo has become an emotive subject, one that draws fire from a variety of moral-ethical standpoints, and is not infrequently a target of grass-roots activism. Much of this critique is directed at “brand bullies”—global multinationals—rather than at the phenomenon of branding itself, but the line often seems blurred. There is a widespread perception that the branding of things, people, and knowledge is a distinctive creation of the postindustrial West, which is now being exported around the world, leading to the erosion of cultural diversity and local identities in new and unprecedented ways.

Viewed against this backdrop, my article was clearly making some unusual claims. Specifically, I was trying to separate the history of branding from the history of capitalism and to locate its origins outside the recent history of Western societies. As an anonymous reviewer of my Current Anthropology submission pointed out (and as I had initially failed to realise), this had already been done some years earlier, by social historians Gary Hamilton and Chi-kong Lai. In their contribution to The Social Economy of Consumption (1989), Hamilton and Lai convincingly argued that a complex system of commodity branding—applied to goods such as rice, tea, wine, scissors, and medicines—had existed in late imperial China, where it can be traced back to the Song dynasty of the 10th century ad (see, more recently Hamilton 2006; also Eckhardt and Bengtsson 2009, but note their incorrect dating of the non-Chinese material). Their basic claim—that branding was neither uniquely “modern,” “Western,” nor “capitalist”—resonated with my own negative response to Naomi Klein’s description of the “origins” of branding in postindustrial Europe. It seemed to me that, in its fundamentals, what Klein was describing could be quite easily traced across much earlier periods of human history: the anonymity of mass consumption, the shift of corporate enterprise from creating novel products to image-based systems of distinction, and the emergence of generic labels that attach (often highly imaginative) biographies to otherwise indistinguishable goods and packaging.

THE BRAND: BETWEEN MARXIST CRITIQUE AND MARKET-SPEAK

All of this was quite familiar from my earlier research into the origins of urban societies and writing systems in the Middle East, between around 4000 and 3000 BC. For instance, many examples of what is regarded as the earliest Egyptian writing appear on labels attached to a wide range of commodities such as textiles, oils, and alcoholic drinks that were stored and transported in standardised ceramic containers. These labels not only provide bureaucratic information relating to quality and provenance, but also carry images that link the commodities in question to royal ceremonies and to particular locations in which the king performed rituals to ensure the fertility of the land (Wengrow 2006: 198–207, 2008: 9–10).

A broadly comparable system of product marking can be documented in ancient Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq), where a series of administrative terms (appearing in texts of the 3rd millennium BC) are used to convey information concerning: “(1) emblems or symbols of deities, households, or individuals, (2) marking tools bearing these emblems or symbols, (3) marks which were the result of applying these tools to animals, human beings or boats and, finally, (4) verbs describing these marking activities” (de Maaijer 2001: 301). Daniel Foxvog (1995) actually translates one such term—which denotes the marking of cattle and other commodities—as “to brand.”

Though clearly of little value when considered in isolation, such instances point towards the possibility that temple and palace bureaucracies in the ancient Near East may have been using systems of marking and notation, not only to monitor the quantity and quality of manufactured goods (as has long been recognised) but also to enhance the value of such products through specialised procedures of packaging and labelling. With such considerations in mind, I began to read more deeply into the history of critical theory and semiotics: mid-20th-century theoretical movements that have become highly unfashionable in the social sciences but which at least offered a starting point for thinking in general terms about branding and advertising as cultural phenomena. What I found there were still stronger claims, formulated within a broadly Marxian perspective, for the exclusively modern character of branding and its transformative effects in postindustrial societies.

Both the German (Frankfurt) and French (semiotic) schools seemed to implicate branded commodities in the decline of modes of subjectivity based on kinship, class relations, and caste, arguing that mass consumption creates a new set of normative identities, tying consumers to the exploitative conditions of capitalist production (e.g., Barthes 1977 [1964]; Horkheimer and Adorno 1996 [1944]). Jean Baudrillard (1968, 1970, 1981), for example, saw modern branding practices as a form of cultural alchemy specific to capitalist modernity and unparalleled in earlier social formations. The brand sign, he argued, brings together in an ephemeral material form two conflicting psychological tendencies: the drive for short-term gratification and the long-term need for transcendence—what we might call, for brevity’s sake, the “Coca-Cola Is Life effect.” The intended outcome is a short-lived transcendence of self that can only be sustained through further acts of purchase and consumption, so that commodity branding ultimately seeks to create a whole pattern of social and economic dependency. More recent critiques, including those offered by anthropologists, tend to reinforce the association of branding with “late capitalism” (e.g., Carrier 1995; Wernick 1991). Even analyses of non-Western advertising (e.g., in contemporary Japan; see Tobin 1992) take Western marketing strategies as their touchstone of comparison, rather than pursuing possible continuities with local or indigenous forms of branding.

Turning to the cultural wing of modern marketing literature, I was surprised to find many overlaps with the critical, Marxian tradition of brand analysis. Although the ancient roots of product labelling are often whimsically mentioned in this literature (with a nod to the ancient Greeks and such things as potters’ marks), branding itself is clearly regarded by many marketing professionals (and professors of marketing) as having only recently become a major player on the field of social change (e.g., Chevalier and Mazzalovo 2004; Holt 2006, 2008; for an exception, see Moore and Reid 2008 and comments below). I was particularly struck by how some marketing analysts had picked up on the earlier psychoanalytical literature, arguing that the appeal of brands is rooted in the “quick fixes” they offer for deep existential crises in modern societies, generating distinct and self-perpetuating forms of dependency between consumers and their most coveted products (e.g., Holt 2002: 87, 2004). The major difference seemed to be that 21st-century experts on marketing treat the construction of selfimage through mass consumption as a basis for commercial strategies that, if properly managed and targeted, might transform an ailing business or public institution into a global success story. Their 20th-century ancestors, by contrast, thought the same material-psychological drives were destroying the moral fabric of society in general. Even Raymond Williams’s (1980 [1960]) characterisation of marketing as a modern form of “magic,” “symbolism,” and “mythology,” I discovered, has been enthusiastically incorporated into professional brand-speak, but as an endorsement of good practice rather than a form of psychological warfare waged on the weak by the powerful (e.g., Roberts 2004).

In short, it was becoming clear to me that arguments for the modernity of commodity branding have been widely mounted (both within and outside academia), often from very diverse standpoints, and in the service of very different social agendas. But what happens to these various, entrenched positions on contemporary brand culture if the West actually turns out to be a relative latecomer in its adoption of systematic product branding? What are the implications of decoupling brand economies, as social and historical phenomena, from capitalist modes of production? What happens if we elect to see contemporary Western capitalism as just one context (or better, set of contexts) in which branding—a phenomenon common to large-scale societies since before the time of the Great Pyramids—has taken on new forms and cultural permutations? Before exploring these questions and some of the answers offered in this volume, it seems important to summarise the evidence presented in “Prehistories of Commodity Branding” (Wengrow 2008).

PREHISTORIES OF COMMODITY BRANDING

In a seminal piece on the social construction of value, the anthropologist Igor Kopytoff (1986) argued that commodities are not things in themselves but rather situational entities: elements of material culture (or persons) that have become temporarily enmeshed within a particular set of social and moral codes; codes that determine the character and pace of their circulation. Commodity situations are those in which the exchangeability of one thing for another becomes, for a time, its most socially salient feature. In the same work, Kopytoff also observed that the production of commodities is “a cultural and cognitive process: commodities must not only be produced materially as things, but also culturally marked as being a certain kind of thing” (p. 64). It is this latter observation that has remained underdeveloped in anthropological studies of value and exchange, a neglect that finds its counterpart in recent archaeological theories of commoditisation (e.g., Renfrew 2001, 2005) that pay little attention to concrete mechanisms of sealing, labelling, and marking.

Specialised forms of product labelling in premodern societies have tended to be studied in one of two ways. They may be considered in terms of their administrative roles (i.e., their use in monitoring the circulation of people and goods—an approach usually taken by archaeologists and anthropologists). Or they are studied from a purely iconographic perspective, with various kinds of labels treated as art objects, divorced from the commodities to which they were attached, and hence from the world of social transactions (an approach usually followed by art historians; but for a notable exception, see Winter 2000). My primary aim in “Prehistories of Commodity Branding” was to question this artificial separation of functions (and of modern disciplinary interests) as well as the wider reconstructions of ancient economy and society that it supports. I attempted to do this through a detailed study of how commodities were sealed and marked in Mesopotamia during the transition from village to urban life (ca. 7000–3000 BC).

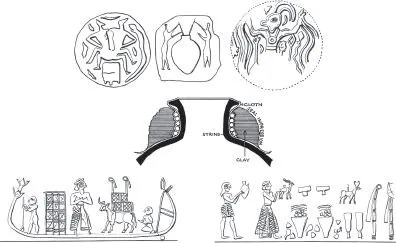

The kind of sealing practices with which I was concerned involve two basic physical components: (1) the seal itself, often a highly crafted object made of some hard substance, which carries an intaglio design that is impressed by rolling or stamping; and (2) the sealing, made of a soft adhesive substance such as clay or wax, which serves the dual functions of receiving the seal image and holding shut the closure of a container through its attachment over the lip (Figure 1.1, centre). Sealing practices of this kind are no longer a standard feature of commercial life. But their replacement by industrial adhesives and synthetic wrapping materials is a relatively recent development, and mass-produced (“skeuomorphic”) replicas of seal impressions continue to be featured on labels for a wide range of modern commodities, notably those—such as alcoholic drinks, perfumes, dairy products, and other comestibles—that must be sealed for practical as well as social reasons, to avoid spoiling through exposure. This modern (symbolic) use of seal imagery to evoke nostalgia and authenticity is perhaps responsible, in part, for disguising the fact that sealing practices of this kind, when viewed from a historical perspective, constitute the earliest-known technique for mechanically reproducing a crafted image (and note their striking absence from Walter Benjamin’s famous [1999 (1936)] essay on “the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction”).

Figure 1.1. Images impressed onto the clay sealings of commodity containers in early Mesopotamia and south-west Iran. (above: stamped impressions, 5th–early 4th millennium BC; below: rolled impressions, 4th millennium BC), and an illustration of the sealing mechanism (centre).

In the alluvial plains between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in Mesopotamia, the practice of sealing containers with impressed images in this manner can be traced back to the late 7th millennium BC, some 2,000 years prior to the emergence of cities in the same region. The function of sealing practices in these early village economies has been much debated (see, e.g., Ferioli ed. 1994). What role did they play i...