- 229 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lithic Analysis at the Millennium

About this book

The original research papers in the volume provide a broad review of current approaches to the study of lithic technology from the Palaeolithic to the present. The contributions address both with analytical techniques and interpretive issues. Collectively, they increase our understanding of issues such as tool function, means of production, raw material sourcing and exchange systems, and the evolution of human cognition, social organization and symbolic behavior.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Analytical Techniques in Lithic Analysis

10

A Refitter's Paradise: On the Conjoining of Artefacts at Maastricht-Belvédère (The Netherlands)

Dimitri de Loecker1, Jan Kolen1, Wil Roebroeks1 and Paul Hennekens2

Abstract

Although refitting analysis has been known as a valuable methodological tool for more than a century, it is only seldom explored on a systematic basis for the interpretation of stone age sites. This article reviews the results of a long-term refitting programme for the Middle Palaeolithic site complex at Maastricht-Belvédère. The Netherlands. On the basis of the Belvédère example, the potential value of such refitting programmes for the reconstruction of Palaeolithic site taphonomy as well as early human behaviour will be discussed. Specific attention is paid to the impact of post-depositional processes on artefact scatters, the reduction processes of Middle Palaeolithic core technologies, the complex life histories of single stone tools, the use of space by early humans and the spatial dynamics of lithic technologies.

10.1 Introduction

This wonderful feat was first performed by my friend Mr F. C. Spurrell of Daxtford. On first thoughts the thing seems utterly impossible, and it is obvious that no flake can possibly be replaced upon an implement unless one lights on the exact spot where the implement was made, and finds both implement and flakes in position. (Smith 1881, 582)

Until the late 1970s the Middle Palaeolithic archaeological record of The Netherlands was made up exclusively of lithic surface collections and diagnostic stray finds (Roebroeks 1980, among others). In the Dutch Southern Limburg area these surface scatters were located in the higher landscapes (outside the river valleys) in particular and investigations concentrated mainly on typo/technological interpretations. It was only from the 1980s onwards, and especially as a result of the detailed long-term excavations carried out at Maastricht-Belvédère, that information on a river valley became available as well. The emphasis shifted towards the excavation of stratigraphically 'sealed' and well-preserved settlement remains in sedimentation areas, e.g., the river valleys with a fine-grained fluvial matrix, and also the loess covered plateaux. The well excavated artefact scatters at Belvédère documented a number of different 'on-site' activities and provided a better understanding of early human behaviour in a small segment of a 250,000 year old riverine landscape (Roebroeks 1988; Roebroeks et al. 1992, 1993).

Together with this shift of interest, a wide range of new questions were introduced into Dutch Palaeolithic archaeology along with a series of analytical tools to answer them. As a result, the excavated levels at Belvédère have generated new information on absolute dates, stratigraphy, palaeoenvironment, wellpreserved spatial distributions of artefacts, food procurement and in particular on the technological strategies used (de Loecker forthcoming; Roebroeks 1988; Roebroeks et al. 1992,1993; van Gijn 1988,1989; Vandenberghe et al. 1993). In addition to the use-wear studies (van Gijn 1989) and a very detailed lithic description of the flint assemblages (de Loecker forthcoming; Roebroeks et al. 1997; Schlanger 1994, 1996; Schlanger & de Loecker 1992), conjoining studies were the most instrumental at Belvédère for making inferences on early human behaviour.

It has often been stated that refitting of lithic artefacts proved essential to the (re) construction of reduction strategies. As well as providing typological and technological documentation, the method can be used in the investigation of site formation processes (both human and non-human). Combined with distribution maps, refitting proves very useful in locating areas where artefacts were made, used and discarded, and in determining which artefacts were transported. By doing so refitting can inform us about the spatial and temporal characteristics of 'sites' (Cahen et al. 1979; Hofman 1981; Roebroeks 1988; Roebroeks et al. 1997). Although refitting has a history of more than a 100 years, its analytical importance has only been recognised during the last three decades. In particular, the investigations and refitting results by LeroiGourhan & Brézillon (1966) and Cahen et al. (1979) at the Upper Palaeolithic sites of Pincevent and Meer II respectively and the 'Big Puzzle' symposium organised at Monrepos (Neuwied) in Germany in September 1987 (Cziesla et al. 1990) turned out to be significant milestones in European stone age archaeology. Moreover, they inspired many researchers to go on, or start, using the method of conjoining artefacts.

The aim of this article is twofold; it intends to deal with the methodology of conjoining artefacts and investigate the significance of refitting as a major analytical tool. Moreover, conjoining data from the Dutch Middle Palaeolithic sites at Maastricht-Belvedere will be used to illustrate its informative value for archaeology. Different research topics will be tackled by using information from different excavated areas (sites). The conjoined artefact compositions from Sites K and J are used for monitoring vertical and lateral postdepositional disturbances. Reconstruction of lithic reduction processes, the identification of the recycling and reworking of flakes and tools and the typological transformations during the uselife of these tools are illustrated by the refitting results of Sites A, G, C, K and J. Furthermore, the conjoined material from Site K is used to identify artefacts which were produced elsewhere and were subsequently transported to the excavated surfaces. In addition, site K is relevant for the identification of activity areas, such as loci of manufacturing, use, resharpening or discard and the question of temporal relationship between different loci within the same 'site'.

10.2 Refitting: a short historical review

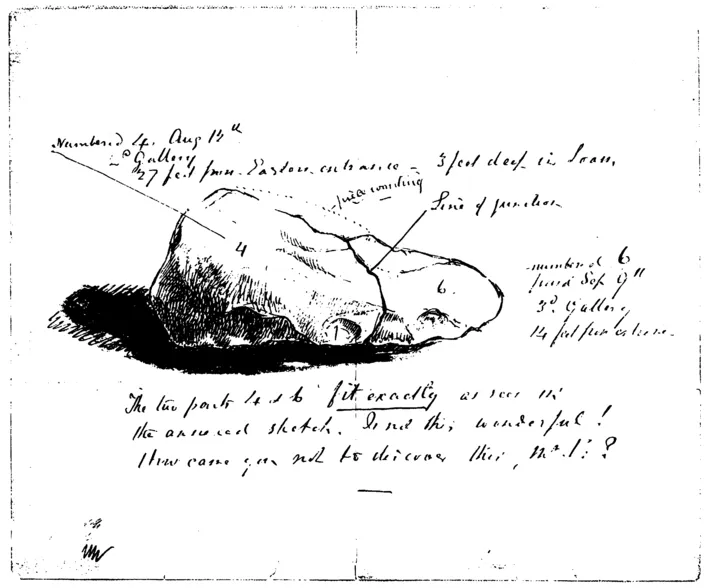

The method of conjoining artefacts goes back to the 19th century. One of the earliest refits was reported from the Palaeolithic site at Brixham Cave, Devon, England (Evans 1897, 512-6; Lubbock 1872; Pengelly 1867, 1874; Prestwich 1873). During the August/September 1858 excavations, conducted by Pengelly and his colleagues, two pieces of a handaxe were recovered at different times and from different areas of the cave but from the same geological layer. According to Evans' description of Brixham cave (1897) some time afterwards (possibly at the end of 1858 or the beginning of 1859) Falconer discovered that the two fragments could be rejoined so that the true character of this tool was seen (Fig. 10.1), although no further inferences were made (Berridge & Roberts 1990). In the late 19th century other 'restorations' of broken tools were established at the Upper Palaeolithic site of Solutre near Mâçon, France (de Mortillet & de Mortillet 1881, 1903) with the conjoining of broken Solutrean leaf points (feuille de laurier) found some distance from each other. The first successful attempts to systematically refit flint artefacts were undertaken at the Middle Palaeolithic site of Crayford in Kent, England, where Spurrell refitted a number of flakes onto a flint handaxe and was able to reconstruct the original form of the flint nodule and the flint knapping technology employed (Smith 1881; Spurrell 1880a,b). However, he did not go beyond the observation that the nodule had been reduced on the spot. In the words of Arts & Cziesla (1990) he was in fact only 'restoring' the artefact's original form. Spurrell's refitting skill is referred to again in a monograph on the Egyptian site at Medum (Petrie 1892, 18). Here, he was able to conjoin a sequence of 17 well made blades in their original order of production and reconstruct their mode of manufacture.

In the late nineteenth century, a very systematic and detailed refitting analysis was also done by Worthington G. Smith (Evans 1897, 598-600; Smith 1892, 1894). In Man, the Primeval Savage (Smith 1894, 126-8) he described the elaborate conjoining and 'replacing' of the Acheulian flint assemblage from Caddington, England. A total of more than 500 artefacts were refitted in about three years (1890-1893). Not only was his working method very similar to the one we are still using today but he also interpreted some of the results in terms of human behaviour.

It is remarkable that some of the cores found by me axe of a certain colour, or naturally marked in some peculiar way, and that no flakes of a similar colour or marking have been found. I assume that the flakes were struck off these cores for some special purpose, and carried to some other position not lighted on by me. Again, some flakes axe of a peculiar colour, or naturally marked in special way quite distinct from any core; these flakes, I suppose, must have been struck off elsewhere, and brought to the spot examined by me.

(Smith 1894, 128)

In addition to these interpretations on artefact transportation he also made inferences on recycling, (re) sharpening and modes of flake and tool production/manufacture. In fact his analysis was a reconstruction of reduction schemes avant la lettre. Smith also undertook refitting, but with less success, at the Palaeolithic 'floors' of Stoke Newington Common in North London (Smith 1883, 1884, 1894) and Round Green in Luton, England (Smith 1916).

Another remarkable early conjoining of artefacts was established by de Munck (1893). At the Lower/Middle Palaeolithic quarry site of StSymphorien-Hardenpont, Spiennes, Belgium, he managed to refit an almost complete Levallois core; only the larger prepared flakes could not be refitted as they had probably been transported to another location. As Otte noted (1995) this is probably the first true description and interpretation of a Levallois core in Belgium. In its early days refitting was not only confined to Palaeolithic material; for example at a Neolithic findspot near Dundrum Bay, Ireland (Archer 1881), part of a flint pebble, consisting of 22 flakes, was restored. Refits are also reported from the Neolithic flint mining industry at Spiennes Belgium (Cels & Depauw 1885-1886). Moreover, the publications of Henri-Martin 1907, 1909 show that the conjoining of faunal remains was not unusual either.

Figure 10.1: Brixham (Windmill Hill) cave. Falconer's sketch of an ancient broken and refitted handaxe (round-pointed lanceolate form). Note the text written underneath the sketch: 'The two parts 4:6 fit exactly as seen in the annexed sketch. Is not this wonderful! How came you not to discover this Mr. P?' (after Falconer's sketch, late 1850s-early 1860s, and used with the kind permission of the trustees of the British Museum).

Refitting was used sporadically during the 19th and early 20th centuries, and until the 1960s mainly for technological reconstructions. From the 1960s onwards new excavation methods involving more precise documentation of finds were introduced for Palaeolithic sites. Through the innovative use of refitting at Pincevent (Leroi-Gourhan & Brezillon 1966) it became clear that the potential of the method exceeded reconstructing proced...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Lithic Analysis at the Millennium: Introduction

- I Interpretative Approaches to Lithic Analysis

- II Analytical Techniques in Lithic Analysis

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Lithic Analysis at the Millennium by Norah Moloney,Michael J Shott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.