In the broadest sense all writing is about yourself. Even your laundry list. Wise readers have always known that words reveal the person. Every kind of prose—exposition, argument, description—tells us something about the writer.—Thomas S. Kane and Leonard J. Peters, Writing Prose, 3

Words that convey no information may nevertheless move carloads of shaving cream or cake mix, as we all know from television commercials. Words can start people marching in the streets—and can stir others to stoning the marchers. Words that make no sense as prose can make a great deal of sense as poetry. Words that seem simple and clear to some may be puzzling and obscure to others. With words we sugarcoat our nastiest motives and our worst behavior, but with words we also formulate our highest ideals and aspirations. (Do the words we utter arise as a result of our thoughts, or are our thoughts determined by the linguistic systems we happen to have been taught?) To understand how language works, what pitfalls it conceals, what its possibilities are, is to understand what is central to the complicated business of living the life of a human being.—S.I. Hayakawa, Language in Thought and Action, vii

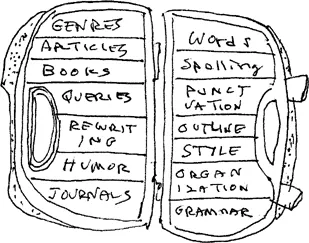

Literally speaking, tools are tangible devices that we use to make or do things. But a broader definition of tools includes anything we use to accomplish a task. In Academic Writer’s Toolkit, our tools are strategies and suggestions to aid in the process of writing. Before choosing specific tools, let’s begin with a look at the term “academic” and at academic writing, in general.

Defining Academic Writing

There are a number of definitions of the term “academic” in popular culture, most of them negative. Dictionary definitions, for the most part, tie the term to scholarship and university settings. One stereotype suggests that academics are so deeply involved in their research and other scholarly pursuits that they are often unaware of what is going on in the “real world,” the world outside the academy. These academics are generally viewed as incapable of functioning in this real world.

Another stereotype suggests that academics focus on theoretical concerns without any regard for practical matters. These stereotypes include absent-minded professors—often viewed as inept, boring, even ridiculous. The term “academic” functions as a framing device for all the negative attitudes listed above. This frame also affects our perceptions about what we will find when we read academic writing, but there’s no reason why academic writing can’t be as interesting and vibrant as that of the best travel writers and others who write for the general public.

I understand academic writing to mean expository writing, generally done in university settings, that observes certain rules and conventions about what is appropriate as far as the content and style of what is written are concerned. In the passage that follows, by Thomas S. Kane and Leonard J. Peters from Writing Prose, we find a more comprehensive discussion of exposition:

Different kinds of writing achieve different purposes. On the basis of controlling purpose, we traditionally divide all prose into three kinds: narration, description, and exposition. Of these, exposition is especially important to the college student since much of what he reads, and most of what he writes, is expository prose. Exposition is writing that explains. In generally, it answers the questions how? And why? If we go into any university library, most of the books we find on the shelves are examples of exposition. (169)

There are many different kinds of academic writing—from book reviews and scholarly essays to monographs, theses, doctoral dissertations, and books. But just because a written text is academic doesn’t mean it must be boring or filled with jargon. You can offer your readers answers to the “why” and “how” questions that Kane and Peters mention in a readable and accessible style—and should work hard to do so.

Some academic writers adopt a style full of hypersyllabic Latinate words and jargon with a purpose in mind. These writers are concerned with technical matters or complicated concepts and are writing for specialized audiences of other academics familiar with the jargon used. In such cases, the use of this kind of writing is understandable.

Philosophers, for example, are notorious for writing in a convoluted style that is often unintelligible and impenetrable to anyone except other philosophers. Consider the following passage from Immanuel Kant’s masterwork, Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals:

Since the universality of the law governing the production of effects constitutes what is properly called nature in its most general sense (nature as regards form)—that is, the existence of things so far as determined by universal laws—the universal imperative of duty may also run as follows: “Act as if the maxim of your action were to become through your will a universal law of nature.”

This extremely complicated sentence, sixty-eight words long, expresses one of Kant’s most important and influential ideas: the existence of a “categorical imperative.” This idea, of acting as if our actions were to become universal has been, it turns out, one of the most fundamental concepts in Western ethics. But because of the complex nature of Kant’s ideas and the complicated sentence structure found in this passage, the writing is difficult to read and understand.

Not all philosophers write this way. Depending on the purpose of the writing and the audience addressed, even philosophers can be informal, conversational, or irreverent. Consider, for example, this course description written by the philosopher Robert Nozick in the Harvard University bulletin:

Philosophy 25: The Best Things in LifeA philosophical examination of the nature and value of those things deemed best, such as friendship, love, intellectual understanding, sensual pleasure, achievement, adventure, play, luxury, fame, power, enlightenment, and ice cream.

He lists some of the “best” topics included in his course and ends his description with a playful and comedic touch—ice cream. Since professors need to “sell” their courses, they sometimes write course descriptions that will attract students.

Woody Allen has seized upon the college bulletin course description genre and written a wonderful parody of the typical course description in “Spring Bulletin,” which appeared in the New Yorker in 1967 and was later published in Getting Even:

Philosophy 1: Everyone from Plato to Camus is read and the following topics are covered: Ethics: The categorical imperative and six ways to make it work for you. Aesthetics: Is art the mirror of life, or what? Metaphysics: What happens to the soul after death? How does it manage? Epistemology: Is knowledge knowable? If not, how do we know this? The Absurd: Why existence is often considered silly, ...