![]()

1

COPING IN COUPLES

The Systemic Transactional Model (STM)

Guy Bodenmann, Ashley K. Randall, and Mariana K. Falconier

Origin of the Systemic Transactional Model (STM)

Individual-Oriented Stress and Coping Theories

Coping with stress has historically been viewed as an individual phenomenon. Specifically, psychodynamic theories focusing on the regulation of intrapsychic conflicts (e.g., Haan, 1977), stimulus-oriented approaches focusing on the impact of critical life events on humans (e.g., Dohrenwend & Dohrenwend, 1974), as well as reaction-oriented theories (e.g., Selye, 1974) emphasizing endocrine and physiological reactions of individuals under stress were typically individual-oriented. In addition to these theories, Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) prominent and internationally recognized transactional theory of stress is also in line with the individualistic conceptualization of stress and coping. In this theory, personal appraisals of characteristics of the situation (i.e., significance for the person, characteristics of the situation such as representing threat, loss, damage, challenge) and one’s own available resources to respond to these demands are evaluated by the individual. The individual’s appraisals of the situation will determine a) whether this situation is perceived as stressful (or not), and b) the intensity of the stress experienced. Once the event has been appraised, the individual reacts both physiologically and psychologically (i.e., stress emotions), and engages in stress-related behavior (e.g., approach or avoidance behavior). Therefore, the experience of stress is a result of the transaction between the individual and his/her environment (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Although this approach ascertains that, for example, dysfunctional individual coping may have detrimental effects on the social environment, and thus coping is viewed as embedded in social context, stress and coping are still conceptualized as an individual affair.

From Individual to Dyadic View of Stress and Coping

Starting in the early 1990s, theoretical approaches aimed to expand traditional individual approaches to stress and coping to specifically understand stress and coping as a systemic issue. Specifically, the Systemic Transactional Model (STM) by Bodenmann (1995) as well as other approaches in the early 1990s (relationship-focused coping by Coyne & Smith, 1991; empathic coping model by DeLongis & O’Brien 1990; congruence approach by Revenson, 1994) or the 2000s (developmental contextual model of dyadic coping, Berg & Upchurch, 2007; relational-cultural coping model by Kayser, Watson, & Andrade, 2007) are the first known theories that started to perceive stress and coping as a social process rooted in close relationships, with a specific focus on the romantic partner. The assumption of interdependence between romantic partners (Kelley et al., 1983), which views partners as having a strong and frequent mutual influence on each other across multiple life domains, became a key feature of dyadic coping. Therefore, in the context of stress, one partner’s experience of adversity is not limited to himself/herself, but affects the experience and well-being of the romantic partner as well. Folkman (2009) praised this extension of the original transactional theory by stating that ‘dyadic coping is more than the sum of two individuals’ coping responses’ (p. 73). The assertion that one partner’s stress and coping experiences are not independent of their partner’s stress and coping represents a relational and interdependent process and is a cornerstone of modern dyadic coping concepts (Acitelli & Badr, 2005; Bodenmann, 1995, 1997, 2005; Kayser, 2005; Lyons, Mickelson, Sullivan, & Coyne, 1998; Revenson, 1994, 2003; Revenson & Lepore, 2012; Revenson, Kayser, & Bodenmann, 2005).

Different dyadic coping models have been proposed. One line of research emphasized congruence or discrepancy between the partners’ coping efforts by analyzing the effects of similar versus different individual coping strategies (e.g., problem-versus emotion-focused coping) of the partners facing a stressful event (e.g., Revenson, 1994). Congruence or discrepancy in individual coping strategies such as problem-solving, rational thinking, seeking social support, escape into fantasy, distancing, and passive acceptance are analyzed on a dyadic level.

Coyne and Smith (1991) expanded upon Lazarus’ transactional approach (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) by considering partners’ coping contribution to the other partner’s well-being. Originally, this approach was developed in the context of couples dealing with one partner’s severe health problems, where the ill partner’s health-related stress was defined as a shared fate. Coping in this context represents a ‘thoroughly dyadic affair’ where a mutual exchange of taking and giving occurs. Coyne and Smith (1991) distinguished three forms of relationship-focused coping: (1) active engagement (e.g., involving the partner in discussions, inquiring how the partner feels, and instrumental or emotional engagement in active problem-solving), (2) protective buffering (e.g., providing emotional relief to the partner, withdrawing from problems, hiding concerns from the partner, denying worries, suppressing anger, and compromising), and (3) overprotectiveness (e.g., dominant, aggressive, or submissive strategies to avoid strong emotional involvement).

Along similar lines, DeLongis and O’Brien (1990) proposed the concept of empathic coping, which encompasses: a) taking the other’s perspective, b) experiencing the other’s feelings, c) adequately interpreting the feelings underlying the other’s non-verbal communication, and d) expressing caring or understanding in a non-judgmental helpful way. A significant conceptual contribution of this approach is that coping extends beyond the goal of solving a specific individual problem and focuses on the benefits for the relationship of shared, responsive coping. This approach also identifies a set of highly destructive coping strategies (e.g., criticism, ignoring, confrontation, or minimizing the frequency of contacts), which predict relationship dissolution in highly dysfunctional couples.

Berg and Upchurch (2007) proposed a developmental contextual model of dyadic coping that is theoretically close to the systemic transactional model (STM; Bodenmann, 2005) regarding shared appraisals and common dyadic coping, but enlarges this model regarding the context of severe chronic disease. The model embeds the coping process in a developmental and historical perspective regarding the different stages of dealing with disease across the lifespan (young couples, middle-aged couples, late adulthood couples) and historical times. Berg and Upchurch (2007) suggest that dyadic coping may vary according to these factors, especially the stage of disease (anticipatory coping, coping with initial symptoms, coping with treatment, daily management), but also socio-cultural aspects (health-related beliefs, access to healthcare, perception of symptoms, role division, individualistic versus collectivistic orientation etc.). Dyadic coping is further shaped by gender, marital quality, illness ownership, and illness severity. Thus, a complex set of variables is considered in the prediction of dyadic coping in the context of chronic illness.

Systemic Transactional Model (STM) of Stress and Coping in Couples

The STM model (Bodenmann, 1995, 1997, 2005) is based upon these above mentioned assumptions (e.g., interdependence between partners’ stress and coping processes) and postulates that one partner’s daily stress experiences, his/her behavior under stress and well-being have a strong and frequent impact upon their partner’s experiences in a mutual way (Kelley et al., 1983). Thus, stressors directly or indirectly can always affect both partners in a committed close relationship. As such, even if a situation concerns primarily one partner, his/her stress reactions and coping affect the other and turn into dyadic issues, representing the cross-over of stress and coping from one partner to the other.

According to STM, partners’ well-being is strongly intertwined, and their happiness is dependent on one another. In this approach a romantic relationship is compared to a couple rowing on the lake. Their boat can only advance if both partners row synchronically and with the same strength; otherwise it turns around in a circle and does not make any progress in moving forward. Therefore, STM emphasizes the interdependence and mutuality between partners, meaning that the stress of one partner always also affects the other one, but also that the resources of one partner expand the resources of the other, creating new synergies. This is true with regard to stress from daily hassles (e.g., work stress) and more severe stressors (e.g., dealing with a chronic illness). For example, one partner’s stress from his/her day at work, can negatively affect the other partner in the evening if the stressed partner was not able to successfully cope with the stress on his/her own (Randall & Bodenmann, 2009). Often the stressed partner comes home upset, withdrawn, or preoccupied, and this negative mood can spill over into the relationship causing the non-stressed partner to experience stress as well (Neff & Karney, 2007; Story & Bradbury, 2004; Westman & Vinokur, 1998). A similar stress spillover process can be observed if one partner has a severe illness (e.g., cancer, heart disease), has lost a beloved person, or has to care for an elderly parent.

Appraisal Processes in STM

The original individual-oriented transactional stress theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) differentiated between two individual-oriented appraisals: (1) primary appraisals, which are defined as the evaluations of the significance of the situation for one’s well-being, and (2) secondary appraisals, which are defined as the evaluation of the demands of the situation and one’s resources to respond to these demands. Bodenmann (1995) expanded the concept of primary and secondary appraisals by including an interpersonal aspect, which focuses on different evaluations of both partner’s independent appraisals as well as their joint appraisal.

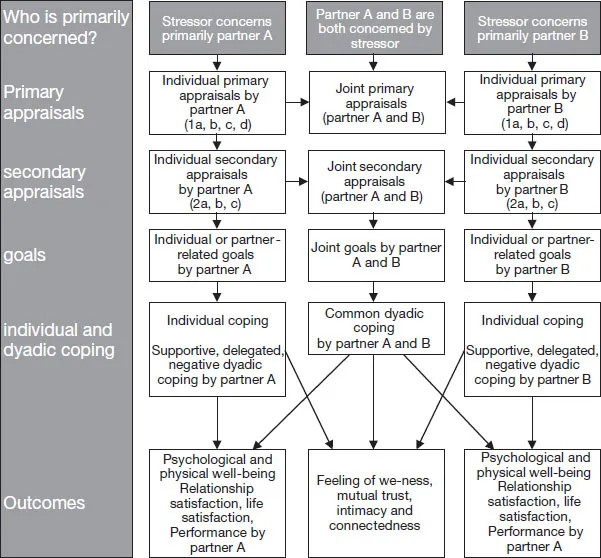

Within the primary appraisals STM differentiates four forms: 1a-appraisal corresponds to the original primary appraisal by Lazarus and Folkman (1984) evaluating the significance of the situation and its profile for the individual (e.g. threat, loss, damage, challenge). 1b-appraisal means the evaluation of Partner B’s appraisal by Partner A (and vice versa). In the 1c-appraisal, the partners evaluate whether the other may have recognized one’s appraisal of his/her appraisal; while the 1d-appraisal consists of a comparison of one’s own and the partner’s appraisal examining potential congruence or discrepancy, resulting in a we-appraisal. In the secondary appraisals, STM proposes three different appraisals: 2a-appraisal means one’s own evaluation of one’s own resources in response to the situation’s demands. 2b-appraisal stands for the partner’s evaluation of the other’s resources, and in the 2c-appraisal partners evaluate congruence or discrepancies in appraisals, resulting in we-appraisals regarding resources. These appraisals lead to individual, couple-related, or joint goals and finally result in individual, partner-oriented coping (supportive, delegated, negative dyadic coping), or common dyadic coping (see Figure 1.1). These different forms of dyadic coping will be described in more detail below.

FIGURE 1.1 Appraisals and goals in the STM

Bodenmann, 2000

Among the different forms of appraisals, joint appraisals (we-stress) gained increased attention. Studies show that joint appraisals (i.e., appraisals by both partners) are significantly linked to dyadic coping and dyadic adjustment in couples in which one partner was diagnosed with cancer (e.g., Checton, Magsamen-Conrad, Venetis, & Greene 2014; Magsamen-Conrad, Checton, Venetis, & Greene, 2014). For example, in couples where one partner was suffering from a chronic disease, Checton and colleagues (2014) found that dyadic appraisals were positive predictors of partner’s support, but also of patient’s own health condition management. Manne, Siegel, Kashy, and Heckman (2014) further support these findings in women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. Shared awareness of cancer-specific relationship impact predicted higher levels of mutual self-disclosure and higher mutual responsiveness. These findings support the notion that we-appraisals are beneficial for patients and partners in their adjustment to illness, while discrepancies in appraisals are associated with higher depressive symptoms in partners (McCarthy & Lyons, 2015). As will be shown below, we-appraisals and we-disease are important aspects of STM.

Factors Affecting the Dyadic Coping Process

The types of coping partners may engage in depend on various factors including (a) the locus of stress origin (Partner A, Partner B, both Partner A and B, or external factors such as circumstances or chance), (b) the direct or indirect involvement of Partner A, Partner B, or both, (c) the general and situational resources of both partners, (d) their individual-oriented, partner-oriented, and couple-oriented goals, (e) their situational and general motivation (e.g., commitment for the relationship) as well as (f) aspects of timing such as whether the stressor affects both partners at the same time or wheather a partner experiences the stress subsequent to his/her partner. When external factors are responsible for stress occurrence, dyadic coping might be more likely (external attribution) than when one partner caused the stress by imprudence, incompetence, or inanity. However, dyadic coping is also likely when one partner caused the stress by his/her inadequate behavior (which would generally lower the likelihood of dyadic coping), but the other partner has partner-related goals (‘I care about my partner independently of why he/she is in this situation’) or couple-oriented goals (‘I am only happy when my partner is happy as well, thus I have to engage in dyadic coping to smooth his/her stress’). In sum, cognitive, motivational, and situational processes are complex and dynamic and affect whether partners rely on dyadic coping and what forms of dyadic coping they choose.

The Process of Dyadic Coping

STM assumes that partners express their stress verbally and/or non-verbally and with implicit or explicit requests for assistance. These expressions of stress are then perceived and decoded by the responding partner within the primary and secondary appraisals described above (see Figure 1.1). He/she may either fail to respond, ignore or dismiss what his/her stressed partner has expressed, engage in his/her own stress communication or offer dyadic coping that reflects his/her own r...