eBook - ePub

Forecasting for the Pharmaceutical Industry

Models for New Product and In-Market Forecasting and How to Use Them

- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Forecasting for the Pharmaceutical Industry

Models for New Product and In-Market Forecasting and How to Use Them

About this book

Forecasting for the Pharmaceutical Industry is a definitive guide for forecasters as well as the multitude of decision makers and executives who rely on forecasts in their decision making. In virtually every decision, a pharmaceutical executive considers some type of forecast. This process of predicting the future is crucial to many aspects of the company - from next month's production schedule, to market estimates for drugs in the next decade. The pharmaceutical forecaster needs to strike a delicate balance between over-engineering the forecast - including rafts of data and complex 'black box' equations that few stakeholders understand and even fewer buy into - and an overly simplistic approach that relies too heavily on anecdotal information and opinion. Arthur G. Cook's highly pragmatic guide explains the basis of a successful balanced forecast for products in development as well as currently marketed products. The author explores the pharmaceutical forecasting process; the varied tools and methods for new product and in-market forecasting; how they can be used to communicate market dynamics to the various stakeholders; and the strengths and weaknesses of different forecast approaches. The text is liberally illustrated with tables, diagrams and examples. The final extended case study provides the reader with an opportunity to test out their knowledge. The second edition has been updated throughout and includes a brand new chapter focusing on specialized topics such as forecasting for orphan drugs and biosimilars.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Forecasting for the Pharmaceutical Industry by Arthur G. Cook in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Past and the Present

Things are more like they are now than they ever were before.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

The future is like the present – only longer.

Goose Gossage

The Inaccuracy of Forecasting

Predicting the future is difficult. A historical look at forecasting over time suggests that we have continually tried to predict the future … and have continually failed to do so with any accuracy. Figure 1.1 indicates the four major challenges when trying to predict the future.

Predicting the future is quite difficult and forecasting accuracy generally is challenged by uncertainties around key assumptions. This text will highlight ways in which this uncertainty can be turned into a positive factor – informing decision makers about uncertainty to increase their awareness in their decision making. Forecasts always contain bias. Sometimes this is the result of data collection methodologies, sometimes it is contributed by the depth of conviction of key opinion leaders, and sometimes it is simply the result of a loud, vocalized stance. Bias is inevitable, but hidden bias is the bane of the forecaster … and contributes to sub-optimal decision making.

Figure 1.1 The challenges of forecasting

The balance between ‘too general’ and ‘too detailed’ is difficult to define a priori. An example of a ‘too general’ forecast is one that is a simple spreadsheet where patients are first multiplied by share and then by price per therapy to generate revenue. This is a valid forecast algorithm, but once more subtle questions are asked – such as, are there different patient segments, how is share constructed, and what is the compliance rate – the forecast loses its utility. At the other end of the spectrum are forecasts that are ‘too detailed.’ These forecasts tend to take the form of complex algorithms and multi-paged spreadsheets with many formulae. This also is a valid forecast algorithm, but the transparency and transferability of the forecast itself becomes quite low.

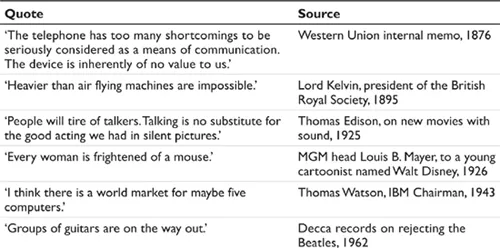

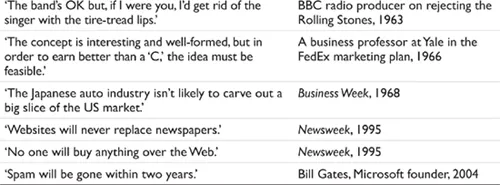

In this text we will address these four main challenges to forecasting. First, we will transform the uncertainty in forecasting into a perspective that enables more informed decisions. We will tackle bias head on, identifying the most prevalent sources of bias in pharmaceutical forecasting and suggesting methods for control of bias factors. The final challenge – balance between ‘too general’ and ‘too detailed’ – is a function of corporate culture and what is acceptable within an organization. This text will, however, examine the characteristics of each extreme and suggest approaches to balanced forecasting. Table 1.1 presents some forecasts by ‘thought leaders’ in their respective fields.

Table 1.1 Even the experts get it wrong sometimes

Sources: O’Boyle, J. (1999), Wrong!: The Biggest Mistakes and Miscalculations Ever Made by People Who Should Have Known Better, New York: Penguin Putnam, Inc.; Also, see http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Incorrect_predictions [accessed 15 December 2015].

We look at these examples today and chuckle – how could the experts get it so wrong? But we have the advantage of hindsight. At the time the comments were made, they surely reflected the current thinking of these individuals and organizations. The simple lesson – that even the experts get it wrong – is a good one to bear in mind as we review in later chapters the role of expert judgment in forecasting.

A more subtle – and just as important – lesson is to reflect upon the pressures that must have existed on the forecaster in industries associated with the individuals who made these statements. If I am a forecaster for personal computers and the chairman of IBM has made a public statement that he believes the world market for computers is five, chances are that I will be affected by this statement in my view of the future. We will discuss the issue of bias in forecasting in each of the subsequent chapters.

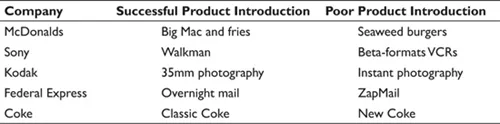

Are companies any better at forecasting than individual experts? The results in Table 1.2 suggest that companies also have a mixed record when it comes to forecasting. Table 1.2 presents some new products that have been introduced by large companies and categorizes the products as ‘leaders’ and ‘laggards’ with respect to their relative success in the global markets. These companies all have successful new product launches to their credit, but also introduced products to the market with limited success. It is reasonable to assume that the planning for the new products included forecasts that presumably justified the product launches. What went wrong? We will explore the answer to this question when we discuss new product forecasting in Chapter 3.

Table 1.2 The success of new product introductions

Forecasting in the Pharmaceutical Industry

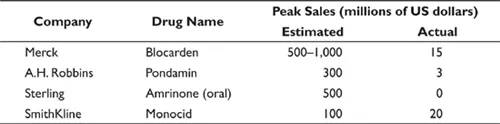

What about examples from the pharmaceutical industry? In 1985 there was an article published in Pharmaceutical Executive that examined the linkage between successful new product launches and a company’s stock price. The authors stated that ‘Projections of the sales of new drugs, especially of blockbuster drugs, have almost always been too high. Investors have been burned so many times with this game that it is difficult to understand why they continue to play it.’1 In support of this statement have a look at the data in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3 Blockbusters that went bust

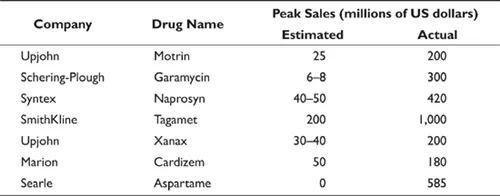

At the other end of the scale are products that achieved forecasts beyond their initial expectations (see Table 1.4). These examples are offered as evidence that some blockbuster drugs are not recognized as such when initially forecast.

Table 1.4 Beyond expectations

The data in Tables 1.3 and 1.4 are those cited in the 1985 article in Pharmaceutical Executive. If updated for sales after 1985 the discrepancy between forecast and actual performance would be even greater.

Do we have more recent examples than those from 1985? Unfortunately, no. The pharmaceutical industry has become more circumspect about publishing internal company estimates of forecast potential for new products. The speed with which financial – and increasingly legal – markets respond to forecasts has dissuaded publication of internal forecast data. Moreover, the accuracy of a forecast is highly dependent upon the the datapoints used in the comparison of ‘actual’ to ‘forecast’ performance. For example, actual performance of a product – compared to its forecast one month previously – is typically more accurate than actual performance compared to a forecast from two years previously. Without knowing the time period of the comparison, claims of forecast accuracy cannot be judged.

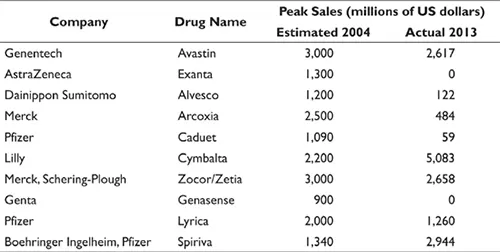

Although we have no concrete public data by which to judge the accuracy of forecasting in the pharmaceutical industry we do have some indicators. In January 2004 an article in MedAdNews presented a list of ‘future blockbusters.’2 These date from 2004 and the reported sales for 2013 are presented in Table 1.5.3 As time progresses, comparing actual data for these products relative to their forecast data will give us an indication of what improvements – if any – have occurred in forecasting pharmaceutical products between 1985 and the present. Of course, the best source of data lies within each company, and readers of this text from within the pharmaceutical industry will be able to judge their company’s relative success in pharmaceutical forecasting from review of these internal data.

Table 1.5 Pharmaceutical blockbusters predicted in 2004

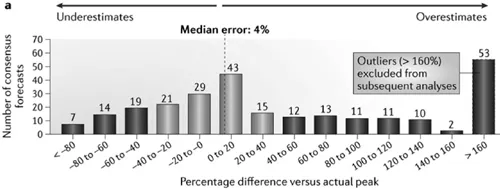

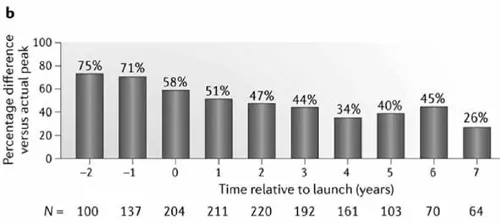

An intriguing article was published in 2013 that took a retrospective look at forecast accuracy for products launched between 2002 and 2011.4 The article examined consensus forecasts (as opposed to internal manufacturer forecasts), but the authors posited that the consensus forecast is ‘not generally that different from other forecasts in our experience.’ The results are shown in Figures 1.2 and 1.3. The authors cite two major conclusions: most consensus forecasts were wrong, often substantially; and accuracy remained an issue even several years post-launch. The data in Figure 1.2 suggest that the majority of consensus analyst forecasts have an error of more than 4 percent. The data in Figure 1.3 suggests that forecast error remains as high as 45 percent even six years post-launch.

History, clearly, provides few comprehensive and simple solutions for forecasting in the future. The lessons of history, however, do provide us with the insights that have led to the best practices we will discuss in the remainder of this book. Before moving on to these solutions, let’s examine the current state of forecasting with respect to its role in pharmaceutical companies. This current state also drives many of the best practices we will discuss.

Figure 1.2 Accuracy of pre-launch forecasts

Figure 1.3 Accuracy of post-launch forecasts

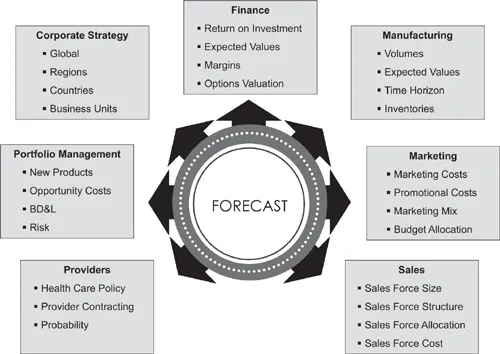

The Current State: Influences Across Functions

Forecasting feeds into and influences many other functional areas within an organization (see Figure 1.4). These linkages may be unidirectional (where forecasts feed into decisions made by the other functional areas) or bidirectional (where the forecast is used to quantify the effects of market changes envisioned by other functional areas). The links reflect the varied uses to which a forecast can be applied – such as revenue planning, production planning, resource allocation, project prioritization, partnering decisions, compensation plans, lobbying efforts, and so forth. These varied uses, and the effect of forecasting on many functional areas in an organization, reflect the first major challenge of forecasting – meeting the needs of varied and diverse stakeholders.

Figure 1.4 Forecast links to other functional areas

The link between forecasting sales revenue and unit volumes is an obvious one; however, the form of the forecast required may differ between these two. The unit volume forecast needs to include detail above that required for revenue demand – including information on sampling units, safety stock, and the distribution of product amongst the various packaging forms. These links should be bidirectional. In other words, the forecaster must understand the needs of the recipients of the forecast in order to...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- 1 The Past and the Present

- 2 The Forecasting Process

- 3 New Product Forecasting

- 4 In-Market Product Forecasting

- 5 Specialized Topics in Pharmaceutical Forecasting

- 6 Thoughts for the Future

- 7 PharmaCo – A Forecasting Case Study

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Appendix C

- References

- Index