eBook - ePub

Structural Changes in U.S. Labour Markets

Causes and Consequences

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Structural Changes in U.S. Labour Markets

Causes and Consequences

About this book

During much of the 1980s, US wage growth has been unexpectedly slow in the face of relatively low unemployment rates and high capacity utilization rates. This collection of papers resulting from the Wage Structure Conference held by the Federal Research Bank of Cleveland, November 1989, helps explain labour market behaviour in that period. The contributors - academic and research economists in labour economics - provide a comprehensive assessment of the current state of the wage-setting process in the US labour market.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Overview

Randall W. Eberts and Erica L. Groshen

Despite apparently tight labor markets, wage inflation in the late 1980s was much lower than most observers anticipated. The Wall Street Journal quoted one noted economist as saying, “The most interesting phenomenon in the United States today is the existence of enormous labor shortages in some areas accompanied by no upward pressure on wages.”1 The article went on to state that the reasons for this phenomenon raise doubts about forecasts that wage pressures would soon contribute to inflation.

Several explanations were offered at that time for the slow nominal wage growth that occurred during the second half of the decade. Chief among the factors cited was a reversal in labor-management psychology about wage increases, brought on in part by productivity declines, a severe economic downturn, and increased foreign competition. The common perception was that during the 1970s, workers, with the consent of management, felt entitled to automatic wage increases that were at least in line with inflation. The demand for “3 percent plus cost of living” was a common refrain around many negotiating tables. This mindset evaporated as workers saw massive job losses during the twin recessions of the early 1980s and as managers faced mounting foreign competition that eroded market share and placed downward pressure on domestic prices. Instead of focusing on wage increases, negotiations centered on wage concessions in exchange for job security.

In addition to a change in the psychology of wage-setting behavior, institutional changes were also cited as possible causes of sluggish wage growth. Mitchell (1989), in comparing the wage pressures of the 1980s with those of the 1960s, concludes that recent changes in labor-market institutions have pushed wage-setting in a more competitive direction. With the decline of the proportion of employment in the union sector and in big firms, jobs are less likely to be cushioned from labor-market forces by union contracts and bureaucratic personnel practices.

Changes in demographics, particularly the greater participation of women in the labor force, were also said to figure into the moderate wage growth that occurred during the 1980s. To the extent that women are less attached to the labor force than are men, they could provide a buffer by filling vacancies during tight labor markets and by leaving the labor force during slack periods.

The questions that faced many policymakers and analysts during this period were twofold: What was really behind this apparent change in wage behavior, and was the change permanent or temporary? To provide a better understanding of these issues, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland commissioned a set of papers by prominent labor economists to provide a careful and comprehensive analysis of some of the important developments that took place in the labor market during the 1980s. The research focuses primarily on labor-market behavior and industrial relations practices that could explain the macroeconomic relationship between unemployment and wages and the effect of this relationship on output and employment stability. Four of the six papers included in this volume deal with compensation practices, the use of lump-sum and profitsharing payments and fringe benefits, and the structure of union contracts. The remaining two studies examine the effects on wages of increased pressure from international competition and changing labor-force demographics.

I. Comparisons Across the Last Three Decades

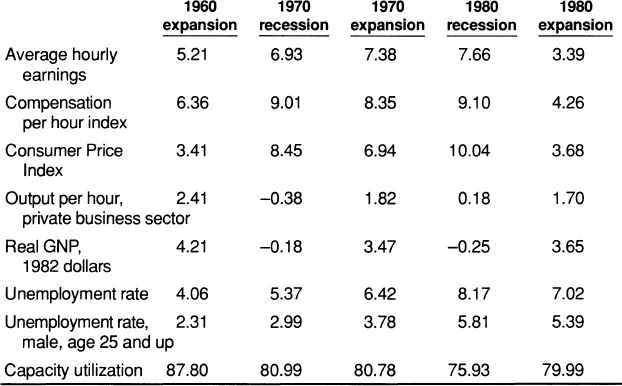

Was wage behavior different during the 1980s than during the preceding two decades? This brief section argues that this may indeed have been the case. Many analysts have noted that nominal wage growth during the expansion of the 1980s fell far short of the wage growth experienced during the expansions of the 1970s and even those of the 1960s (Table 1). The same relatively sluggish growth rates of the 1980s are also evident for the broader measure of compensation per hour, which includes fringe benefits, a growing component of employee compensation. This casual observation alone might tempt one to conclude that fundamental changes in the structure of wage determination and worker compensation during the 1980s dampened the upward pressure on wages.

Table 1: Economic Conditions in Previous Decades

NOTE: The 1960 expansion is defined as the period between 1961:QI and 1969:QIV. The 1970 recessions include the periods 1970:QI to 1970.QIV and 1973:QIV to 1975:QI. The 1980 recessions include the periods 1980:QI to 1980:QII and 1981:QII to 1982:QIV.

SOURCES: Average hourly earnings in the private business sector, the compensation per hour index, output per hour in the private business sector, unemployment rates, and the Consumer Price Index are obtained from the Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Hourly earnings, compensation per hour, and output per hour are shown as annual percentage changes averaged over the respective time periods. The Consumer Price Index and the unemployment rates are average rates over the respective time periods. The capacity utilization rate for manufacturing is obtained from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and is the average rate for the time period. Real GNP is obtained from the Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. It is shown as the average annual percentage change over the time period.

However, leaping to that conclusion ignores differences in economic conditions across the past three decades. Although observers in the 1980s generally perceived labor markets to be extremely tight (particularly during 1988 and early 1989), typical measures of labor-market tightness do not support this view. In fact, the minimum unemployment rate during the 1980 expansion (5.2 percent) was higher than that of the expansions of the previous two decades (3.4 percent during the 1960s and 4.8 percent during the 1970s). In addition, the maximum rate of capacity utilization was lower during the 1980 expansion than during the expansions of the 1960s and 1970s (84.4 percent versus 91.6 percent and 87.3 percent, respectively). Therefore, it is not clear whether the slow wage growth that occurred during the 1980s resulted from structural changes in wage-setting practices or simply from differences in business conditions.

One way to partially disentangle these effects is to ask the conceptual question: What would have happened to wages if the expansions of all three decades had shared the same economic conditions and differed only in the way wages responded to changes in the economic environment? We use a simple econometric technique to estimate the wage behavior separately for each of the last three decades. These estimates record how wages responded to economic conditions in each decade, and are then used to simulate the net nominal wage change that would have taken place if the wage behavior unique to each decade had responded to alternative economic conditions.

We follow a variant of the wage-change model used recently by Wachter and Carter (1989) and earlier by Gordon (1982). Annual changes in average hourly nominal earnings are explained econometrically by annual changes in the unemployment rate, capacity utilization, labor productivity (measured by output per hour), the GNP implicit price deflator, and the Consumer Price Index (CPI, all items for urban workers). Other specifications of the wage-change model are possible, and many have been posited and estimated. This simple specification is based on the premise that wages respond to pressures in the labor market and to inflation expectations. Therefore, changes in the unemployment and capacity utilization rates proxy changes in the tightness of labor and product markets. The CPI reflects workers’ expectations of price inflation. Labor productivity changes measure workers’ contribution to production and, consequently, employers’ ability to grant higher wages. The GNP implicit price deflator captures changes in producer prices, which also reflect employers’ ability to pay higher wages.

These relationships are estimated separately, using quarterly observations for each decade. A variable that takes the value of one during quarters marked by national recessions is also included in the regression to account for business-cycle effects.

Since our main interest in this exercise is to demonstrate wage behavior under similar economic conditions, we do not dwell on the estimates of individual coefficients. Suffice it to say, however, that most of the variables in Table 2 appear to have the expected effect on nominal wage changes. For the most part, higher nominal wage increases are associated with higher inflation expectations, increased capacity utilization, gains in labor productivity, and higher producer prices. However, the relationship between changes in nominal wages and unemployment rates is not what one would normally expect, showing a positive correlation in the 1970s and 1980s. These results are consistent with periods of stagflation during the 1970s and with the long, gradual recovery of the 1980s, when the rate of wage increase declined as inflation moderated and unemployment rates fell.

1960 | 1970 | 1980 | |

|---|---|---|---|

Intercept | 0.465 | 6.022 | 0.473 |

(0.63) | (7.43) | (2.11) | |

Consumer Price Index (percentage change, lagged one quarter) | 0.887 | 0.082 | 0.325 |

(2.07) | (1.18) | (5.70) | |

Unemployment rate (percentage change) | −0.018 | 0.027 | 0.051 |

(−1.74) | (1.84) | (6.09) | |

Capacity utilization rate (percentage change) | 0.045 | 0.150 | 0.142 |

(0.63) | (2.66) | (6.19) | |

Labor productivity (percentage change) | 0.286 | −0.221 | 0.002 |

(2.07) | (−2.70) | (0.03) | |

GNP implicit price deflator (percentage change) | 0.271 | 0.138 | 0.498 |

(0.77) | (1.12) | (5.60) | |

Recession (variable = 1 for quarters marked by recession) | −0.387 | −0.674 | −0.138 |

(−1.10) | (−1.80) | (−0.43) | |

R2 | 0.89 | 0.52 | 0.99 |

NOTE: Observations are quarterly and percentage changes are year over year. Separate regressions are run for each decade. T-ratios are in parentheses.

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations.

The net effects of these differences in the relationship between nominal wage changes and changes in economic conditions are shown in Table 3. The bottom row is of primary interest. The first entry in that row is the average annual nominal wage change that would have taken place in the 1980s if labor during that period had responded to economic conditions in the same way it did during the 1960s. In this hypothetical case, wages would have increased 6.43 percent annually on average during the 1980s. Subjecting the wage behavior that prevailed during the 1970 expansion to 1980 economic conditions yields a slightly higher annual growth rate of nominal wages of 6.65 percent. Both of these growth rates are substantially higher than the 4.24 percent increase that actually took place during the 1980s.

Structure (relationship between conditions and wages) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

1960 | 1970 | 1980 | ||

Explanatory variables (economic conditions) | 1960 | 5.41 | 6.17 | 3.65 |

1970 | 9.52 | 7.51 | 6.97 | |

1980 | 6.43 | 6.65 | 4.24 | |

NOTE: The values are the average annual percentage changes in nominal hourly earnings during the decade. Simulations are performed by multiplying the explanatory variables for a given decade by the c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Overview

- 2. International Trade and Money Wage Growth in the 1980s

- 3. Lump-Sum Payments and Wage Moderation in the Union Sector

- 4. Profit Sharing in the 1980s: Disguised Wages or a Fundamentally Different Form of Compensation?

- 5. The Decline of Fringe-Benefit Coverage in the 1980s

- 6. Indexation and Contract Length in Unionized U.S. Manufacturing

- 7. Gender Differences in Cyclical Unemployment

- 8. Macroeconomic Implications

- Contributors

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Structural Changes in U.S. Labour Markets by Randall E. Eberts,Erica L. Groshen,Lee Hoskins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.