eBook - ePub

The Strategic Alliance Handbook

A Practitioners Guide to Business-to-Business Collaborations

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Strategic Alliance Handbook

A Practitioners Guide to Business-to-Business Collaborations

About this book

Strategic alliances offer organisations an alternative to organic growth or acquisition when faced with the need to develop the business to a new level, innovate in terms of products or services or significantly reduce costs. The Strategic Alliance Handbook is a clear and complete guide to the nuts and bolts of the process behind successful collaborations. The book enables readers to understand the commercial, technical, strategic, cultural and operational logic behind any alliance and to establish an approach that is appropriate for the type of alliance they are seeking and the partner organisation(s) with whom they are working. Whether you are an alliance executive, responsible for the systems, strategy and performance of your organisation's alliancing programme or an alliance manager needing to ensure the success of a given partnership, The Strategic Alliance Handbook is an essential guide.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Strategic Alliance Handbook by Mike Nevin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 Alliance Success Factors

Background/Research Methodology

This book is founded on extensive research that has identified a list of common success factors (CSFs) that consistently feature in successful strategic alliances (successful as defined by both or all partners in the relationship).

The original secondary research was conducted by Alliance Best Practice Ltd (ABP) during 2002–3. The research was called secondary because it examined the literature available at the time regarding successful strategic alliances.

The research methodology was relatively simple:

• identification of any research that focused on why alliances succeed;

• identification of any common factors in successful alliances.

ABP identified over 27,000 instances of international (different countries) and domestic (same-country) alliances. These instances came from a wide range of published material by practitioners, academics and consultants.

Having identified over 27,000 instances of alliances, ABP went on to assess how many of these relationships were deemed successful. The ABP definition of success was simple: all parties to the relationship agreed that the alliances delivered the expected or hoped-for results, or better.

ABP found less than 3,000 alliances that satisfied these criteria (the actual figure was 2,840, or 10.52%).

ABP then asked the follow-up question – Why? Why were these relationships successful? We then collected all the reasons for success and found that some reasons seemed to feature in a statistically significant manner, meaning that their occurrence could not be explained by luck or coincidence alone.

An example may help to make this clearer. In our research we discovered that trust was a success factor that was a feature of successful alliances. That is not to say that all successful alliances have a high degree of trust; but it is to say that a high proportion of successful alliances did have a high degree of business-to-business trust.

We designated these recurring success factors as common, hence the term ‘common success factors’, and its acronym, CSF.

Somewhat later in our research, while I was teaching a class of alliance managers for Oracle in Geneva, I was offered another interpretation of the acronym which I also feel holds true: ‘common sense factors’!

It is important to note that not all CSFs are present in all successful relationships.

Having conducted the original secondary research, we then turned our attention to primary research and shared our findings with over 340 members of the Association of Strategic Alliance Professionals in order to validate the original findings. What we wanted to know was:

• Do these results make sense?

• Do they resonate with you?

• Do you recognise these factors as desirable in your alliance relationships?

The answer in all cases was a resounding ‘Yes.’

ABP has since used the resulting framework to analyse and diagnose alliance health and effectiveness, and has developed a benchmarking database (the Database) which allows us to score the degree of CSF use in alliance relationships. This scale is graduated 0–100, with 0 representing a situation in which there is no evidence of any CSF usage in the alliance and 100 representing a situation in which all the CSFs are present and working perfectly.

So far over 340 organisations have contributed to the research, which is ongoing. (For a full list of contributing companies identified by business sector please see Appendix 3 – List of Companies).

As of June 2014, the ABP Database of findings from the research contained over 200,000 entries from organisations in multiple sectors. In each case at least three key stakeholders were interviewed in detail:

• executive sponsors – usually responsible for setting strategic direction and primarily concerned with cost benefit analysis;

• alliance executives – usually responsible for managing more than one alliance and principally concerned with managing multiple alliances as efficiently as possible;

• alliance managers – usually responsible for the day-to-day running of a single alliance and most concerned with a specific relationship and its operational challenges.

The research was conducted by telephone and face-to-face interviews with alliance professionals in the following sectors: IT software, IT hardware, systems integration, airlines, manufacturing, logistics, pharmaceutical, financial services, telecommunications and fast-moving consumer goods.

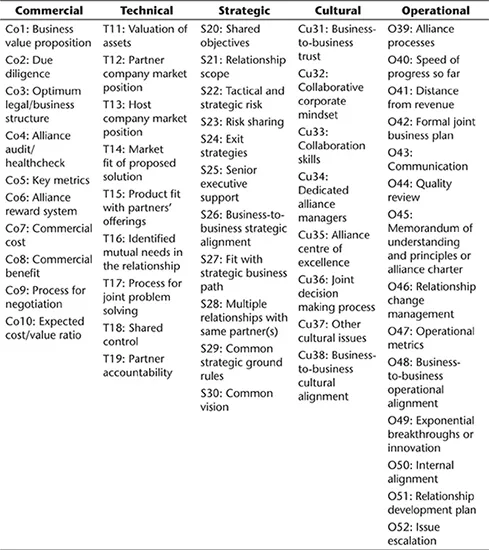

ABP found that there were recurring and consistent common success factors in strategic alliances. The 52 CSFs fall into one of five dimensions or categories:

1. Commercial

2. Technical

3. Strategic

4. Cultural

5. Operational.

All of these dimensions are at play in all strategic alliances, although the degree to which they are important is dependent on geography, business sector, the purpose of the relationship and the stage of maturity of the alliance: (1) opportunistic, (2) systematic or (3) endemic (see Chapters 4 and 15 for explanations of these stages).

Table 1.1 identifies the appropriate dimensions for the full list of CSFs.

Table 1.1 Common success factor list

As mentioned above, not all factors appear in all successful relationships (indeed, it would be remarkable if they did), but Table 1.1 serves to illustrate why some alliance relationships are successful while others are not.

For example, it is entirely possible to have a high degree of synergy and trust in the relationship without generating an equally high degree of commercial value. This is because the commercial proposition has not been identified with appropriate rigour. In such cases organisations get on very well together, but the alliance underperforms in commercial terms because inadequate attention has been given to the commercial or technical factors. Equally, it is possible for two or more partners to hate working together, but for the relationship to be reasonably successful because of the power of the breakthrough value proposition of the product or service being provided by the relationship.

In both cases it can be observed that attention to the missing dimensions would pay significant dividends. The list of factors allows us to develop a number of pragmatic insights:

• Best practice(s) can be developed by combining various CSFs in the most appropriate combination for the situation in which the relationship finds itself.

• The use of a common framework of CSFs allows organisations to initiate and manage alliances more easily since they are all talking a common best practice alliance language which is derived from real life and is synthesised common sense (best practice).

• Further sophistication is possible by combining disparate elements in the model at different lifecycle stages (for example, start-up, ramp to revenue, maturity, extension, decline/renewal).

• The framework allows people to understand that all alliances are unique, but their uniqueness comes from the way individual alliances use the individual elements. Thus the situation can be likened to the human DNA: all people have the same constituent factors, but how they are combined dictates whether people are male or female, light- or dark-skinned, have blue eyes or brown eyes and are right- or left-handed.

This final insight allows alliance professionals to be far more sophisticated in their diagnosis and management of strategic alliances. Until now the tendency was to apply a ‘one size fits all’ solution (we need trust; we need to make money in this relationship; we need a defined process; we need to improve our ability to execute, and so on). Now very flexible long- and short-term action plans can be constructed from the constituent factors.

A Short Explanation of Each of the Common Success Factors

Below is a brief list of the common success factors we found in our research. A longer and more detailed discussion of each of the factors is included in Part III.

COMMERCIAL COMMON SUCCESS FACTORS

Co1: Business value proposition

All parties to the relationship must have a very clear and common understanding of the business value proposition (BVP). In the best cases the BVP is a breakthrough value proposition (that is, a product or service customers cannot currently obtain from other suppliers or combinations of suppliers). Leading companies take great pains to ensure that as far as possible the partnership BVP is difficult to replicate by other consortia. In this way they extend the period during which they can expect to enjoy a market-leading position. The existence of a BVP is critical to alliance success. Although all the other factors may be in place, if you and your partner are not offering customers something they can’t get elsewhere (or offering it for a price at a quality that they can’t get elsewhere), then your relationship is critically hamstrung from the outset. It is a must-have success factor in all your relationships. Those organisations in the Database that do not have this element in place show a very high correlation with failure.

Co2: Due diligence

In many cases a full and formal due diligence process may be inappropriate in the early days of an alliance relationship. However, in the best relationships both parties understand that an assessment of how they will work together before they try is of enormous value. Commonly, organisations perform some form of internal or external diligence around the areas of commercial factors, technical alignment of prospective partners’ products and services, a strategic understanding of where prospective partners are heading, a cultural assessment of the organisations involved, and finally, an assessment of how they will co-operate operationally.

Co3: Optimum legal/business structure

Different alliances have different purposes, and it is important to recognise that a structure that works well for one relationship may not work well for another. Questions such as whether the relationship should be formal or informal and whether the structure should include or exclude an equity element are all important in deciding the best structure. However, bear in mind that the business negotiators on both sides should draw up the overall structure of the relationship before it is finalised by each party’s lawyers.

Co4: Alliance audit/healthcheck

Alliances are typically reassessed regularly to identify dynamic changes in day-to-day operations or because of key personnel changes. However, this CSF refers to the practice of a formal alliance review over an agreed timescale. Typically, this review will be formal in nature and be attended by the full nominated stakeholder teams on both/all sides. This review usually takes place annually and is the means by which original expectations and assumptions are challenged.

Co5: Key metrics

Many organisations are finding that the selection and appropriate support of a balanced set of key metrics is critical to the success of their relationships. When deciding on their set of measurements, best practice companies bear the following factors in mind:

• Commercial success tends to be an effect rather than a cause.

• Causes tend to be leading indicators, and effects tend to be lagging indicators.

In a balanced set, not only do organisations consider the different dimensions (Commercial, Technical, Strategic, Cultural and Operational), but they also consider short-term and long-term influences.

Co6: Alliance reward system

This point is very closely allied to factor Co5 above. Only after they have decided on the important aspects to measure do best practice companies embed the right behaviours for those key metrics. Always remember that the operational level is where the grandest partnering schemes and strategies need to be implemented. At this most basic level it has never been truer that ‘what gets measured gets done’. It is no use an executive team for either partner talking a good game of alliance inter-operation while rewarding direct sales and confrontational behaviour.

Co7: Commercial cost

Most organisations have no idea how much their alliance relationships cost. Many organisations are now looking actively at this area to identify first line costs, such as the cost of the staff employed by both sides to manage the relationship, the joint marketing funds available to both organisations to achieve common goals, and the direct costs of interaction (for example, buildings, R&D and training). However, leading-edge organisations are now going one step further and identifying the second-line ‘add-on’ costs of such things as the time of line managers taken up by alliance initiatives, the opportunity costs of not pursuing suitable initiatives or pursuing them in an ineffective manner, and the costs of knowledge leakage to one’s partner.

Co8: Commercial benefit

It may appear to be stating the obvious that organisations should be clear about the value they receive from their alliance relationships, but in fact many organisations are insufficiently exact when identifying the commercial value they receive. Most can identify new sales and new market share which they would not have received were it not for the partnership. However, many do not allocate value to such aspects as knowledge of new markets or technological services, the innovative opportunities available to them through interaction with their partners, or access to clients which would not otherwise be available. Best practice companies are now trying hard to allocate commercial value to some non-tangible factors. The reason they are doing this is to better understand the full value of their relationships in terms of the only commonly available measure – cash revenue!

Co9: Process for negotiation

It could be argued that good negotiating practice would be best positioned in the ‘Cultural Common Success Factors’ section below. But in the ABP methodology it appears here because it has such a powerful effect on the commercial value of the deals which are agreed. Typically, when negotiating a deal both parties take an adversarial position and believe that for either of them to win, the other must ‘lose a little’. However, in true collaborative relationships both partners understand that they are not looking to strengthen their personal position per se, but rather they are trying to strengthen the value and effectiveness of the relationship. This leads to some interesting insights into what constitutes good negotiating practice in alliance relationships. ABP calls this unusual type of negotiating ‘co-collaborative negotiating’, to emphasise the aspect of understanding and strengthening one’s partner’s commercial position and the role that such a view plays in outstanding alliances.

Co10: Expected cost/value ratio

As discussed earlier, best practice companies are increasingly looking in more detail and with more exactitude at the twin elements of commercial cost and commercial benefit. This allows them to develop cogent views around the cost/value return ratio of selected relationships or alliance programmes. However, this success factor goes slightly deeper than this simple observation. Increasingly, best practice companies are conducting their own internal research to identify similar classes or families of alliances which can be directly compared. When they do so, they discover that increasingly they can start to set expected standards for such relationships; when they do so, the best indicator of success is the expected cost/income ratio. If relationships are not performing to the norms established for good alliance performance, then they are quickly dissolved to save scarce collaborative resources to be used for other and better-performing relationships.

TECHNICAL COMMON SUCCESS FACTORS

T11: Valuation of assets

It is important for both partners to feel that they are receiving equal and reciprocal amounts of value in any balanced collaboration. Consequently, many leading-edge organisations are now beginning to put a monetary value on the assets in the relationship. This is usually a two-stage process. The first stage identifies and quantifies the hard assets (for example, marketing funds, R&D facilities and personnel), and the second usually includes aspects such as intellectual property rights, client mindshare and knowledge transfer. Identifying any actual or perceived differences in value provision in the relationship in this way avoids deep-seated but unspoken disquiet fermenting into active discouragement and sabotage.

T12: Partner company market position

...Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Case Studies

- About the Author

- Reviews of The Strategic Alliance Handbook

- Foreword

- Preface: How It All Began

- Conventions Used in This Book

- How to Read This Book

- Part I Emerging Alliance Best Practice

- Part II Alliance Analysis

- Part III Common Success Factors

- Part IV Special Strategic Alliances

- Part V Developing Alliance Capability

- Appendix 1 About Alliance Best Practice

- Appendix 2 The Alliance Best Practice Database

- Appendix 3 Companies in the Alliance Best Practice Database

- Appendix 4 Definition of Terms

- 5 Further Reading

- Appendix 6 Useful Additional Resources

- Index