- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Collaborative Autoethnography

About this book

It sounds like a paradox: How do you engage in autoethnography collaboratively? Heewon Chang, Faith Ngunjiri, and Kathy-Ann Hernandez break new ground on this blossoming new array of research models, collectively labeled Collaborative Autoethnography. Their book serves as a practical guide by providing you with a variety of data collection, analytic, and writing techniques to conduct collaborative projects. It also answers your questions about the bigger picture: What advantages does a collaborative approach offer to autoethnography? What are some of the methodological, ethical, and interpersonal challenges you'll encounter along the way? Model collaborative autoethnographies and writing prompts are included in the appendixes. This exceptional, in-depth resource will help you explore this exciting new frontier in qualitative methods.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1 |  |

What Is Collaborative Autoethnography?

Collaborative autoethnography (CAE) is a qualitative research method that is simultaneously collaborative, autobiographical, and ethnographic. Putting these three terms together in one definition may appear to be oxymoronic. Ethnography, for example, is the study of a cultural group; therefore, pairing it with autobiography, the study of self, seems contradictory. Despite the seeming inconsistency, some qualitative researchers have succeeded in joining these two conceptual opposites to create a research method called autoethnography (AE). To this relatively recent approach to qualitative inquiry, we are adding another dimension—collaboration.

The notion of collaboration requiring group interaction seems directly at odds with that of a study of self. How can a study of self be done collaboratively? To answer this question, we ask you to imagine a group of researchers pooling their stories to find some commonalities and differences and then wrestling with these stories to discover the meanings of the stories in relation to their sociocultural contexts. The obvious follow-up questions are: If anyone intends to study self, why does he or she want to do it in the company of others? What are the benefits of exploring self in community rather than in solitude? These are the very questions we hope you will ask. Moreover, we hope you ask another question: How does one actually conduct a collaborative autoethnographic study?

In this chapter, we discuss how a study of self can be conducted in the company of others and how a study of individuals can be a catalyst to understanding group culture. We begin by explaining what AE is and then how it relates to CAE. We then discuss CAE as a social science research method and explain how the method preserves the unique strengths of self-reflexivity associated with autobiography, cultural interpretation associated with ethnography, and multi-subjectivity associated with collaboration.

AUTOETHNOGRAPHY

AE is a qualitative research method that focuses on self as a study subject but transcends a mere narration of personal history. Chang 2008, 2011) defines AE as a research method that enables researchers to use data from their own life stories as situated in sociocultural contexts in order to gain an understanding of society through the unique lens of self. This definition highlights two vital aspects of AE also noted by other AE scholars: (1) the use of autobiographic data; and (2) cultural interpretation of the connectivity between self and others (Anderson, 2006; Bochner & Ellis, 2002; Denzin, 1997; Ellis, 2004; Reed-Danahay, 1997). Researchers who embark on autoethnographic research methods have agreed on the importance of “data on the self” as relevant in social inquiry. By taking the liberty of “outing” their own experiences as the subject of exploration, autoethnographers reject “claims to objectivity” and value “subjectivity and researcher-participant intersubjectivity” (Foster, McAllister, & O’Brien, 2006, p. 47). Namely, they occupy dual roles of researchers and participants in their study. This approach to research challenges the hegemony of objectivity or the artificial distancing of self from one’s research subjects. Instead, autoethnographers place value on being able to analyze self, their innermost thoughts, and personal information, topics that usually lie beyond the reach of other research methods.

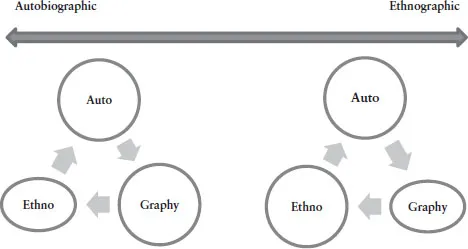

How researchers interject their stories into the research process varies in autoethnographic research. Ellis and Bochner (2000) articulated the interplay among three components—auto, ethno, and graphy—in AE research: “Autoethnographers vary in their emphasis on the research process (graphy), on culture (ethno), and on self (auto)” such that “different exemplars of AE fall at different places along the continuum of each of these three axes” (p. 740). We translate their thinking into a continuum anchoring on two ends, one emphasizing autobiography and the other ethnography (see Figure 1-1). On the autobiographic end, researchers are likely to put more emphasis on self (auto) narration (graphy); on the ethnographic end, researchers focus more on the cultural interpretation (ethno) of self (auto). The continuum of AE research allows researchers of various disciplines to self-select their positionality in telling their interpretive stories. What researchers bring to this method of inquiry is an approach to research that will ultimately reflect their level of comfort with emotive self-disclosure and personal orientation in conducting research.

Attention to self is indeed a unique feature of this method of inquiry. However, AE must be distinguished from autobiography, which focuses on personal stories. Autoethnographers use personal stories as windows to the world, through which they interpret how their selves are connected to their sociocultural contexts and how the contexts give meanings to their experiences and perspectives. Intentional and systematic consideration of various autobiographical data give rise to autoethnographic interpretation that transcends mere narration of their past to help researchers reach explanations of the sociocultural phenomena connected to the personal. They tell stories to explain how they respond to their environments in certain ways and how their sociocultural contexts have shaped their perspectives, behaviors, and decisions. The sociocultural interpretation of self-society connectivity sets this inquiry method apart from other self-narratives such as autobiography and memoir. With this distinctive goal, autoethnographers explore their own experiences to construct interpretive narration (presented most frequently as evocative stories) or narrative interpretation (presented more often in academic discourse).

Figure 1-1 Autoethnography continuum.

Ellis and Bochner, pioneers of autoethnographic work, lean more toward “interpretive narration” (Ellis, 2004, 2009; Ellis & Bochner, 2000). Their approach to AE has been linked to the adjective “evocative” (Ellis, 1997) or “heartfelt” (Ellis, 1999) AE. The focus is on challenging researchers to embrace an approach to writing that favors emotional self-reflexivity as a rich data source. Many followers of this orientation have produced evocative autoethnographies, focusing on personal matters traditionally shunned by social scientists: for example, abortion (Ellis & Bochner, 1992), teen pregnancy (Muncey, 2005), death and grief (Ellis, 1995; Wyatt, 2008), mother-daughter relations in the midst of illness (Ellis, 1996), childhood with a psychotic parent (Foster, McAllister, & O’Brien, 2005), childhood with a “mentally retarded” mother (Ronai, 1996), motherhood with a schizophrenic child (Schneider, 2005), sexual abuse (Fox, 1996), domestic violence (Olson, 2004), bulimia (Tillmann-Healy, 1996), brain injury (Smith, 2005), illness (Ettorre, 2005; Kelley & Betsalel, 2004; Neville-Jan, 2003), pregnancy as a gay couple (Atkins, 2008), and a spiritual journey as an academic (Abigail, 2011; Poplin, 2011).

Anderson (2006), however, was concerned that a narrow focus on “evocative or emotional ethnography may have the unintended consequence” of stymieing the development of this emerging practice (p. 374). Unlike the evocative approach to AE, which can be based solely on the experience of the researcher, Anderson insisted that analytical AE must involve data from others. His advocacy of involving others in autoethnographic studies has not been received favorably by solo autoethnographers (although his suggestion does inform the work of some collaborative autoethnographers). However, his plea for an analytical approach to autoethnographic interpretation is well aligned with the orientation of “narrative interpretation” (the ethnographic end in the continuum). Others (Chang, 2008; Reed-Danahay, 1997) advocate an AE akin to more conventional ethnography, grounded on ethnographic data collection, analysis, and interpretation. This approach has been used for studies of both personal and professional topics. Many examples of analytical autoethnographies have been published. On the topic of the work-life-family balance, Cohen, Duberley, and Musson (2009), Galman (2011), and Geist-Martin et al. (2010)1 stand out. Regarding professional responsibilities in the academy, we can point to works on teaching practices (Duarte, 2007; Hernandez, 2011; Romo, 2004), research agenda (Ngunjiri, 2011), and the role of an administrator (Walford, 2008). These are only a fraction of the autoethnographies written in academic discourse.

We do not argue that one style of expression is superior to the other or that both styles cannot be mixed. The ultimate goal of self-inquiry may differ, depending on philosophical orientations specific to one’s discipline. Whereas those schooled in qualitative social phenomena, as Anderson (2006) described, may adopt more analytic paradigms, others may choose to share the specificity of their experiences in more evocative discourse. All examples we have provided so far have adopted the medium of prose. AE can also be presented in more creative and performative mediums such as poetry (Ricci, 2003) or drama scripts (Cann & DeMeulenaere, 2010; McMillan & Price, 2010; Pelias, 2002). Although means of expression may differ depending on researchers’ personal and professional preferences, Vryan (2006) argues that all kinds of AE engage cultural analysis: “[T]here are many ways analysis via self-study may be accomplished, and the term analytic autoethnography should be applicable to all such possibilities” (p. 406). We agree that it is this embrace of cultural interpretation that distinguishes autoethnography from other autobiographic or self-narrative writings.

The use of self as a window to society gives a particular vantage point to autoethnographers compared to other social scientists because autoethnographic researchers can tap into their most personal thoughts and experiences that are not readily opened to others. In addition, with intimate understanding of their personal data from the beginning, they can significantly reduce the time needed to piece together fragmented data before entering into a holistic interpretation. Despite these benefits, AE has limitations. Since researchers are dealing with self-data all too familiar to themselves, they could be easily influenced by their own presumptions about personal experiences without the benefit of fresh perspectives from others who could question their presumptions. In addition to the danger of self-perpetuating perspectives, a study of one’s self lacks the possibility of demonstrating researcher accountability during the research process because the researcher is also the participant. CAE attempts to overcome the limitations of potentially self-absorbing AE while preserving the wealth of personal data inherent in autoethnographic research.

AUTOETHNOGRAPHY AND COLLABORATIVE AUTOETHNOGRAPHY

AE was popularized as solo work in creative, evocative, and/or analytical AE paradigms within the last two decades. Due to its focus on the researcher self, AE became almost synonymous with the study of a person. However, collaborative projects have branched out of the foundational work of AE. CAE still focuses on self-interrogation but does so collectively and cooperatively within a team of researchers. A variety of labels have appeared in the literature to introduce multi-researcher AE designs, including: duoethnography (Lund & Nabavi, 2008a; Norris, Sawyer, & Lund, 2011; Sawyer & Norris, 2004, 2009), co-ethnography (Ellis & Bochner, 1992), collective AE (Cann & DeMeulenaere, 2010), co/autoethnographic (Coia & Taylor, 2006), CAE (Kalmbach Phillips et al., 2009; Rose, 2008), community autoethnography (Toyosaki et al., 2009), and community-based ethnography (Stringer et al., 1997). These labels grew out of authors’ ingenuity in naming their self-refined methodology, not out of any logical typology of methods. Therefore, some differences among these labels may be merely nuanced and others substantive. In the next chapter, we tease out both nuanced and substantive differences to better understand methodological differences within CAE.

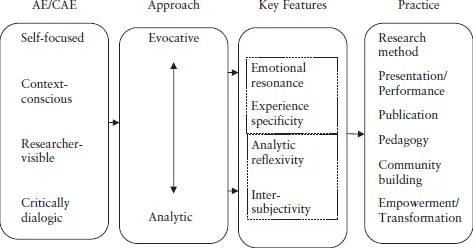

CAE is emerging as a pragmatic application of the autoethnographic approach to social inquiry. Before discussing CAE in depth in the following section, we will compare AE and CAE to identify commonalities and obvious differences (see Figure 1-2).

Figure 1-2 Common dimensions of AA/CAE.

Both AE and CAE are qualitative approaches to research that position self-inquiry at center stage. Though opinions differ about the purpose and scope of AE, the points of agreement remain robust. Drawing from the literature, we see both approaches to be self-focused, researcher-visible, context-conscious, and critically dialogic.

Self-Focused

The researcher assumes the dual role of researcher and research participant; his or her views and experiences are under investigation even as he or she leads the investigation. Anderson (2006) calls this dual role “complete member researcher” (p. 378). In both AE and CAE, the researcher is simultaneously the instrument and the data source.

Researcher-Visible

Critical self-reflection is a corollary to being self-focused. The researcher turns the lens inward to make personal thoughts and actions visible and transparent to the audience. This is a critical perspective that is offered only by AE. The researcher is uniquely positioned to interrogate self and simultaneously be able to understand the nuances behind responses. Thus, autoethnographers are able to make the inner workings of their mind visible. Moreover, the researcher is free to explore this process in detail, as the focal point and not a subordinate element of research practice (Anderson, 2006; Atkinson, Coffey, & Delamont, 1999).

Context-Conscious

As part of the larger social context, the researcher’s experiences and interrogation are presented as they shape and are shaped by specific contexts (Anderson, 2006). Ellis and Bochner (2000) describe the intricacy of studying self in context as follows:

Back and forth autoethnographers gaze, first through an ethnographic wide angle lens, focusing outward on social and cultural aspects of their personal experience; then, they look inward, exposing a vulnerable self that is moved by and may move through, refract, and resist cultural interpretations…. As they zoom backward and forward, inward and outward, distinctions between the personal and cultural become blurred, sometimes beyond distinct recognition. (p. 739)

This continual juxtaposing of self and context is an essential element of autoethnographic work.

Critically Dialogic

The autoethnographic research process allows the researcher to become an active instrument and participant in creating meaning and constructing values (Anderson, 2006; Lapadat, 2009). Because AE enables individuals to occupy both researcher and participant perspectives simultaneously, a rich internal dialogue develops. In CAE, this dialogue is further enriched by each team member’s occupation of these dual spaces as well as the dialogue that is created in community. In either scenario, this chameleonic capacity, unique in autoethnographic work, creates a rich space for meaning-making and analysis.

These commonalities are augmented in the teamwork of collaborative autoethnographers. One obvious difference between these two research methods is that autoethnographers interrogate their self-world by themselves and collaborative autoethnographers work together, building on each other’s stories, gaining insight from group sharing, and providing various levels of support as they interrogate topics of interest for a common purpose. In the teamwork, researchers increase the sources of data from a single researcher to multiple researcher perspectives.

COLLABORATIVE AUTOETHNOGRAPHY

If AE is about interrogating the self to gain deeper understanding of “society and self,” is there room for others in these interrogations? We say, “Yes!” We define CAE as a qualitative research method in which researchers work in community to collect their autobiographical materials and to analyze and interpret their data collectively to gain a meaningful understanding of sociocultural phenomena reflected in their autobiographical data. AE is to a solo performance as CAE is to an ensemble. While the combination of instruments creates a unique musical piece, the success of the composition is dependent on the authentic and unique contribution of each instrument. In CAE, each participant contributes to the collective work in his or her distinct and independent voice. At the same time, the combination of multiple voices to interrogate a social phenomenon creates a unique synergy and harmony that autoethnographers cannot attain in isolation.

In CAE, researchers can alternate between group and solo work. We argue that the combination of individual and group works adds rich texture to the collective work. When the group works together, individual voice is closely examined in community. Others’ questioning and probing add unique depth to personal interrogation. The researchers can then r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Chapter 1. What Is Collaborative Autoethnography?

- Chapter 2. Typology of Collaborative Autoethnography

- Chapter 3. Getting Ready for Collaborative Autoethnography

- Chapter 4. Data Collection

- Chapter 5. Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Chapter 6. Collaborative Autoethnographic Writing

- Chapter 7. Applications of Collaborative Autoethnography

- Epilogue: Our Approach

- Notes

- References

- Appendix A Writing Prompts Used for Individualized Data Collection

- Appendix B Article: “Exemplifying Collaborative Autoethnographic Practice via Shared Stories of Mothering” by Geist-Martin et al.

- Index

- About the Authors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Collaborative Autoethnography by Heewon Chang,Faith Ngunjiri,Kathy-Ann C Hernandez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.