![]()

p.5

In reading this chapter, you will learn to:

• define the whole and parts of ICT4D;

• outline specific features of ICTs and developing countries;

• explain the connection between ICTs and development;

• contrast different development paradigms;

• categorise key theories and concepts of relevance to ICT4D.

This chapter provides an understanding of what ICT4D means, breaking it down into its constituent parts and discussing and explaining each one. As well as defining ICT4D, this will help understand what makes ICT4D different, and how it determines the relation between ICTs and development in both practical and theoretical terms.

1.1. What do we mean by “ICT4D”?

What is ICT4D:

• A Kenyan farmer uses a mobile phone to find the best price for her crops. Is that ICT4D?

• A doctor in India records the details of his patients on a database. Is that ICT4D?

• A multinational company in Argentina installs improved point-of-sale terminals in its supermarkets. Is that ICT4D?

• An African-American teenager from a low-income family uses Twitter to organise a protest against alleged police harassment. Is that ICT4D?

To understand, we have to go back to first principles, and the meaning of ICT4D.

At one level, what we mean by ICT4D is obvious. It’s an abbreviation, and it stands for “information and communication technology for development”. But that raises two immediate questions: what do we mean by “information and communication technology” and what do we mean by “development”?

p.6

And that in turn means we have to define “information”, “communication” and “technology”. The only thing we can take as read in ICT4D is the word “and”.

1.1.1. Defining information and communication

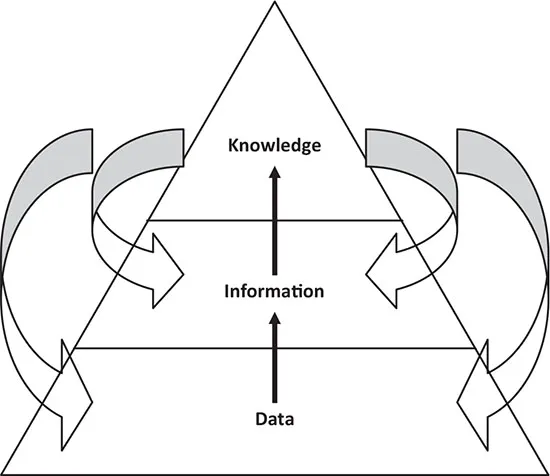

Probably the best way to understand information is as part of three related concepts, illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Data is raw, unprocessed information. This is what you always start with. Often, data consists of descriptions (qualitative data) or numbers (quantitative data) that have been recorded to represent some object, place, event or other phenomenon. For example, the questionnaire responses of community members about their health needs. Data is also produced as part of the routine activities of any person or organisation.

Information is data that has been processed to make it useful to its recipient. This is what comes next. For example, a summary of the analysed responses used by the community health centre manager, laying out in a few graphs and tables the main perceived health needs. Note that amending the old saying about meat and poison, we can say that “one person’s information is another person’s data”: for example, something like details of an individual patient’s health records could be information to a doctor but just data (i.e. requiring further processing, such as adding together) to a hospital manager.

p.7

Knowledge is information that has been assimilated into a coherent framework of understanding: often within the human mind. This comes last and can involve a person receiving information, processing it themselves, understanding it and fitting it into their existing base of knowledge. To complete our health example, once the community health centre manager has read through the analysed responses, s/he will match it against previous information and ideas on provision of health services to the community. Note that, increasingly, knowledge can be stored – even created – by ICTs.

In everyday speech, the words “data” and “information” are often used interchangeably, but in formal terms we can now see that they are different. We can summarise the definitions given above as follows in terms of a forward flow: data is processed into information is assimilated into knowledge (see also Box 1.1). Though note there is also some kind of a reverse flow – see Figure 1.1 – because knowledge explains information, and knowledge filters and processes data.

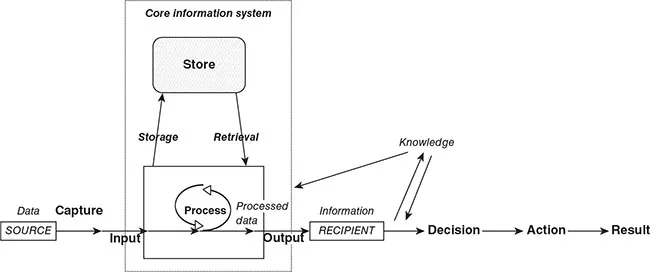

We can represent the process of changing data into information, and information into knowledge in a little more detail, as shown in Figure 1.2. This is a foundational model for the book known as the “information value chain”. It is summarised as consisting of the “CIPSODAR” steps, which can be divided into two parts. First are the “CIPSO” steps associated with the core activities of an information system: Capture (data is first gathered from its source), Input (data is entered into the information system), Process (data is manipulated by categorising it, or filtering it, or totalling it, or performing some other calculation on it), Store (data is held in the information system), and Output (processed data is communicated to a recipient). Then come the “DAR” steps: Decision (the recipient makes a decision on the basis of the information received), Action (some action is taken on the basis of that decision), and Result (this action has some impact on development).

It is a value chain because it shows that data only has developmental value if it becomes information, and information only has value if it is applied to decisions which lead to actions which lead to development results. (Note that sometimes this happens through conversion of information into knowledge – via learning – which is only later applied to a decision and action and result.)

From both Figures, it can be seen that communication is pervasive. Each arrow represents a movement of data: this is communication, and we can therefore define communication as the transmission of data.

p.8

Box 1.1

Data, information, etc: a cooking analogy

When you have all your items of shopping together in a bag, they’re a jumble that doesn’t make much sense. Just the same is true of raw data.

To make sense of your shopping items, you need a recipe. A recipe is explicit knowledge – a framework for understanding your data. Seen in this way, some of your shopping items now become ingredients. The information systems equivalent is that data that are understood are “capta”: those specific items that are relevant to the current situation (on the information value chain diagram, we would indicate those as the specific data that has been captured).

Using the recipe and an oven, pans, food mixer, etc, you then turn your ingredients into something to eat – say, a cake. The information systems equivalent is that you use a combination of knowledge and technology to turn the capta into processed data. The cake is processed data.

It becomes information – data that has been processed to make it useful to a recipient – if someone is hungry. Then they must make a decision to take action: to eat the cake.

Finally, the cake is eaten: an action that leads to results (they are not hungry any more). Perhaps this takes place at a birthday party. Likewise, information is never consumed in a vacuum; it is always consumed in a social context that influences the way the information is perceived, and the impact of its consumption.

And the cake, once eaten, turns into energy that could build muscles; likewise the information, once consumed, turns into knowledge that builds your frameworks of knowledge.

Source: original idea from Norah Stoops

p.9

1.1.2. Defining technology and ICT

There are whole papers, books even, that discuss what is meant by technology, but I will try to keep things fairly simple by teasing out three elements:

a) Technology is a non-human entity. Your hand is not technology. We typically think of technology as a physical device but it can also be intangible: a particular technique or method.

b) Technology applies knowledge. So technology does not occur naturally: it has been created by the build-up of human knowledge; often – though not always – through the formal knowledge-creation process we call science.

c) Technology does something. It has a purpose of undertaking a task such as converting some inputs into different outputs.

Putting those elements together, we can define technology as: “devices or techniques that apply knowledge in order to complete a particular task”.

With that in mind, ICT would be defined as “devices or techniques that apply knowledge in order to process or communicate data”. There are three, increasingly broad understandings of what that means:

• ICT Scope 1: digital ICT – any entity that processes or communicates digital data: smartphones, laptops, computer software, apps, the Internet, etc.

• ICT Scope 2: electrical ICT – any entity that processes or communicates data in electrical or electro-magnetic form: all of ICT Scope 1 plus analogue technologies like radio and TV.

• ICT Scope 3: all ICT – any entity that processes or communicates data in any form: all of ICT Scope 2 plus paper-based technologies like pens, typewriters, books, newspapers, etc.

In this book, we will use Scope 1. So we limit ourselves to digital technologies but note that the technologies of Scopes 2 and 3 are increasingly being digitised.

p.10

1.1.3. Defining development

Just as with the definition of ICT, we can identify three different breadths of understanding of development. In this case, running from broader to narrower:

• Development Scope 3: generic development – any progressive change in a society (for the moment, swerving to avoid the key issue of who and what defines a “progressive change”).

• Development Scope 2: geographically specific development – any progressive change in a developing country. “Developing country” is another minefield. Some people don’t like the term: the idea that countries like the US and UK are “developed” is clearly ridiculous if we equate this with them being the finished article. Hence some prefer to use terms...