![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: Why do we need a new psychology of health?

Health really matters. Because of this, stories about threats to health and miracle cures feature prominently in newspapers and magazines, and we are inundated with tips about how to stay healthy on a daily basis. So alongside advice to quit smoking, drink less alcohol, and say no to drugs, we are routinely encouraged to engage in regular exercise, to eat more fruit, and to pay attention to our weight.

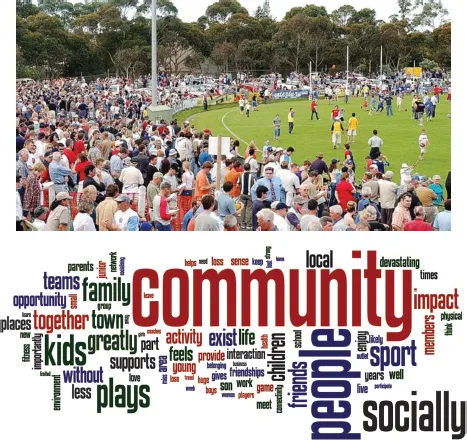

A large body of empirical evidence suggests that this advice is well grounded. We see this, for example, in research on the benefits of physical activity and sports participation in particular. In one study on this topic the Australian Football League joined forces with researchers at La Trobe University’s Centre for Sport and Social Impact (CSSI) to quantify both the health and the economic benefits of physical activity by determining precisely how much participation in sports was worth in financial terms. To do this, they sent a survey to members of 1,677 football clubs asking them not only about football itself, but also about the social connectedness and wider community participation that was associated with their involvement in their club (see Figure 1.1). The findings were striking:

For every $1 spent to run a club, there is at least a $4.40 return in social value in terms of increased social connectedness, well-being and mental health status; employment outcomes; personal development; physical health; civic pride and support of other community groups.

(Centre for Sport and Social Impact, 2015)

Interestingly, this return was not dependent on where people lived, the amount of time they had been associated with the club, or their particular role in the club. More strikingly still, the benefits were not restricted to those who actually played football. Instead, they were observed across the board – among players, coaches, volunteers, and supporters. This suggests that the health and economic benefits of being involved in sport do not just stem from the physical exercise that this entails. Instead, what also matters for health – but what is often overlooked – is the social connection and sense of community that sport provides.

An investment that increases your financial return by over 400% is nothing to scoff at. This is especially true because many (perhaps most) of the advances that are made in health deliver lower returns than this. For example, a comprehensive review by Luce, Mauskopf, Sloan, Ostermann, and Paramore (2006), which looked at return on investment in U.S. health care between 1980 and 2000, found that every dollar spent on treatment produced benefits of $1.10 for heart attack, $1.49 for stroke, and $1.55 for type 2 diabetes. These are important gains, and they point to the undoubted good sense of investing in medical research and treatment. Nevertheless, alongside data of the form produced by the CSSI, they suggest that it makes very good sense to also invest in social activities that are rather less rarefied and that are typically experienced as part of everyday life by those who engage in them.

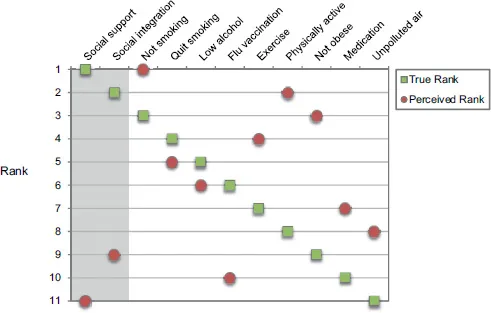

This tendency to turn towards physical and medical factors and neglect the importance of everyday social factors when thinking about improving health was confirmed in research that we recently conducted with 500 members of the general public in the United States and the United Kingdom (Haslam et al., 2018). This involved giving people a survey which asked them to rank 11 factors in terms of their importance for health and mortality. Critically, these were factors whose significance for health had previously been examined by Julianne Holt-Lunstad and her colleagues in an influential meta-analysis of 148 studies involving over 300,000 participants (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010; see also Holt-Lunstad, Robles, & Sbarra, 2017). More specifically, this meta-analysis was interested in comparing the impact that social factors, such as social support and social integration, had on mortality to that associated with established physical risks such as smoking, high alcohol consumption, lack of exercise, and obesity – factors which are the traditional focus of medical research.

Figure 1.1 Illustrations from the CSSI report showing engagement in community football and a word cloud showing what people feel they would lose if their football club disappeared

Note: We tend to see the health benefits of being involved in sport as resulting from the physical exercise that this involves. However, research suggests that these benefits result not only from playing sport but also from the sense of connection and community that sport provides. Moreover, health economists have put a dollar value to this, showing that for every dollar spent in running a football club, the social return on investment was $4.40.

As the green squares in Figure 1.2 indicate, Holt-Lunstad and colleagues’ analysis showed that these social factors were the most important predictors of mortality and that they had an impact that was comparable to (and in fact, slightly higher than) that of the most important behavioural risk factors. Moreover, as recent research has highlighted, social connectedness makes a contribution to mortality risk that is independent of these other health factors (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017). Nevertheless, as the red circles in Figure 1.2 indicate, when members of the general public were asked to rank the importance of these same factors, their ordering was strikingly different. In particular, whereas Holt-Lunstad and colleagues found that social support and social integration were the most important predictors of mortality, our respondents ranked these same factors among the least important.

Figure 1.2 Perceived and true rankings of the importance of behavioural risk and social factors for mortality

Note: This figure highlights the degree to which people tend to underestimate the importance of social factors for health relative to that of established behavioural risks that are the traditional focus of medical research. Specifically, whereas Holt-Lunstad et al.’s (2010) meta-analysis found social factors (specifically, social support and social integration) to be most important for health, the general public perceive these to be among the least important.

So why do people so seriously underestimate the importance of social connectedness and social integration for their health? There is no definitive answer to this question, but it seems likely that multiple factors are at play. One is that the biological mechanisms that impact on health are generally quite well understood theoretically and quite well validated empirically – due in no small part to huge global investment in medical research and technology (Moses et al., 2015; Murphy & Topel, 2010). It is not surprising then, that this has contributed to the dominance of a biomedical model in which the underpinnings of health are understood to be primarily biological or genetic (e.g., see Havelka, Despot Lucanin, & Lucanin, 2009, for a discussion). However, such dominance also appears to be supported by entrenched ideology. This is evident in continued resistance to efforts to expand the medical curriculum beyond the biomedical model (Bowe, Lahey, Kegan, & Armstrong, 2003), and it is also seen in other evidence from our research which suggests that people are more likely to downplay the importance of social factors for health if they have an inclination to follow established authority and convention (Haslam, McMahon et al., 2017).

As a consequence of these and other factors, far less attention has been paid to the role that social processes play in determining health than to biological and medical processes. In part, too, this emphasis reflects the fact that these social processes are harder to pin down. Not least, this is because the ways in which social factors exert their influence on health can vary markedly between individuals – for example, as a function of their living conditions, their culture, their family relationships, their economic circumstances, their work environment, and their social networks. It can also be hard to examine the operation of social factors directly, and so it is often inferred through population-level observations of their impact (e.g., where a lack of social connectedness is found to lead to an increase in depression). We would argue, however, that the existence of this knowledge gap is not a reason to neglect the importance of social factors for health. On the contrary, it is a reason to work harder to try to fill that gap – not only with solid empirical evidence, but also with sound scientific theory.

It is this knowledge gap that the present volume seeks to fill. As we set about this task, we are helped by, and do not want to diminish the significance of, an abundance of previous research which documents the impact and importance of both biological and social factors for health. Nevertheless, what this work is not well placed to provide is an analysis of the psychological processes that mediate between societal dynamics and individual health – an analysis for which, we contend, a new psychology of health is needed. A key reason for this is that, to date, much of the focus of dominant psychological models has been on understanding the psychology of individuals as individuals – the psychology of ‘I’ and ‘me’. What this fails to appreciate is the immense importance of people’s psychology as group members for their health – the psychology of ‘we’ and ‘us’ (Haslam, Jetten, Postmes, & Haslam, 2009; Turner & Oakes, 1986). It is this appreciation that underpins the social identity theorising which informs the novel perspective on health that this book spells out.

In the remainder of this introductory chapter we provide an overview of the biological, psychological, and social approaches that dominate the contemporary health landscape. Rather than explore these in detail (something we will do in later chapters), the goal here is to clarify why a social identity analysis is well placed to provide (1) an overarching framework that integrates and builds upon these existing approaches and (2) a basis from which to develop a new appreciation of the social and psychological dimensions of various physical and mental health conditions. This will then provide a platform both for a detailed exposition of the social identity approach in Chapter 2 and for more forensic exploration of these various conditions in the chapters that follow.

Current approaches to health

Biomedical approaches

Of all approaches to health, the biomedical is unquestionably the most influential. This model understands health primarily through the lens of disease, and it attributes the cause of ill health to some breakdown in normal biological and physiological functioning. In so doing, it gives a clear direction in how best to manage health – and this is to focus on repairing or treating the source of breakdown in the body. There are obvious merits to understanding these physiological influences, not least to treat infectious diseases, which were the main cause of ill health and death until early in the 20th century. However, as Engel (1977) recognised, ill health is not reducible to disease processes alone, and if it were, then there should be much greater consistency in how people experience and respond to disease and its treatment than is actually observed. It is also the case that the health landscape has changed dramatically to one in which chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes, depression, cardiovascular disease, arthritis) have become the prevailing cause of ill health. For these conditions, there is generally no simple biomedical fix that can be administered to restore health.

In light of these changing realities, Engel criticized the biomedical approach as overly “physicalistic” (1977, p. 130) and neglectful of both the human condition and the lived experience of disease (see also Deacon, 2013; Hewa & Hetherington, 1995). In this, he led a revolution in medicine to make health more human by supplementing a biological analysis with awareness of the contribution of psychological and social factors to the experience of illness. This recognises that a person’s health has important cognitive, emotional, and behavioural dimensions and that it is structured by factors such as culture, socio-economic status, family, and religion.

Nevertheless, the challenge has always been to understand how these social and psychological elements present and interact in health contexts to influence outcomes. Engelʼs solution to this was to advocate for a biopsychosocial approach that gives equal weight to the biological, psychological, and social dimensions of health. However, many researchers have argued that the biopsychosocial model is still dominated by the ‘bio’, even in behavioural medicine where efforts are made to integrate the biological and psychological (Epstein, 1992; Suls, Luger, & Martin, 2010) and that the social elements in particular are not well defined (Havelka et al., 2009). The result is that these elements tend to be ‘tacked on’ to medical models rather than properly integrated within them. Amongst other things, this means that the model fails to consider the ways in which each of the three elements has the capacity to restructure the others – so that, for example, a person’s biology is shaped by their psychology, and their psychology is shaped by the groups to which they belong (Caporeal & Brewer, 1995; Ghaemi, 2011).

One consequence of this is that although the biopsychosocial model has proved tremendously appealing, it primarily offers a list of “ingredients” that affect health, rather than a specified theory, and as a consequence it is difficult to test empirically (McLaren, 1998). Moreover, Ghaemi (2009) argues that rather than biological analysis being enriched by a concern for the psychosocial dimensions of health, these limitations have further entrenched the dogma of the traditional biological model. He therefore suggests that if we are to move beyond the limitations of this model and update it in ways that are both theoretically and empirically powerful, we need an approach that is “less eclectic, less generic, less vague” (Ghaemi, 2009, p. 5). As we will see in the chapters that follow, this is a challenge that the new psychology of health takes very seriously and one that it strives to confront head on.

Psychological approaches

Despite the ongoing dominance of the biomedical model (Deacon, 2013), in recent decades psychological approaches have proved increasingly influential as a framework for understanding and managing health. This is largely due to the attention they pay to those factors that Engel identified as vital in shaping the manifestation and course of disease. In particular, approaches that attend to the cognitive and behavioural dimensions of health now provide a strong and compelling evidence base that informs theory and practice related to a wide range of health conditions (e.g., Beck, 2011; Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Harvey, 2004). This work focuses on understanding the combined influence of a person’s thoughts (e.g., their appraisal of symptoms, their sense of personal efficacy) and feelings (e.g., their mood, their sense of loneliness) on their health behaviour (e.g., consuming alcohol, taking medication) and health outcomes (e.g., depression, obesity).

Also prominent is an individual-difference approach that focuses on the way in which health behaviours and outcomes are shaped by psychological traits and personality (e.g....