![]()

PART C

Corpus-Based Lessons and Activities in the Classroom

![]()

C1

DEVELOPING CORPUS-BASED LESSONS AND ACTIVITIES

An Introduction

Part C of this book presents various corpus-based lessons and activities developed for the classroom and intended for a range of language learners. The three subsections represent the primary themes of the lessons or activities: namely, (1) CL and Vocabulary Instruction, (2) CL and Grammar Instruction, and (3) CL and Teaching Spoken/Written Discourse. There may be overlaps in these themes as, for example, a vocabulary lesson may also include some instructions related to the discussion of a specific grammatical feature or structure. The three themes represent common categories of activities in language classrooms, primarily for English language learners, but may also be appropriate in settings such as academic writing instruction or linguistic variation in spoken discourse for native English speakers in various university-level classes. Instructors or materials developers in intensive English programs, ‘study abroad’ courses or workshops, EAP courses for professionals, or writing and grammar courses, or those in sociolinguistics (focusing on the study of linguistic variation) may also beneficially utilize these model corpus-based lessons and activities.

The contributors of these lessons and activities were all my former students in the master’s or doctoral programs at the Department of Applied Linguistics and ESL at GSU. They have all taken my Corpus Linguistics or Technology and Language Teaching courses, which required materials design projects for the short-term language instruction of a linguistic feature (e.g., collocations, linking adverbials, politeness markers, semantic categories of verbs) taught with a corpus tool. The design of the lessons was often based upon a hypothetical classroom with a specific group of learners that the lesson designers were familiar with. However, some of them based their design on an actual class (e.g., an intensive English program course on academic writing) that they were teaching. After completing the program at GSU, most of the contributors found teaching positions at various universities in the US or abroad, teaching inESL/EFL or EAP settings. Others continued to pursue doctoral studies or work in research and administrative contexts. In many cases, the contributors have, over the years, utilized corpus-based lessons in their classes and have presented papers focusing on CL and language teaching in many national and international conferences (e.g., TESOL Convention or the American Association for Corpus Linguistics Conference).

The tools and databases utilized by the contributors include the COCA, AntConc, WordandPhrase.Info, Compleat Lexical Tutor (especially Text Lex Compare and VocabProfile), WebParaNews (WPN), Text X-Ray, and others. Topics range from academic writing to analyzing spoken data to content-based EAP (e.g., legal English and aviation English). The format of the lessons or activities may follow short lesson plans for a course in a designated computer lab (about 45 minutes to an hour) or a homework assignment, with a worksheet distributed to students. Some of the lessons describe a longer sequence of corpus-based instruction or activities, such as combining data gathering and interpretation, a comparison of linguistic features, or students collecting and analyzing their exploratory corpora or completing a writing assignment. After each complete lesson segment or handout, a short interview with contributors, mainly focusing on what they believe are the important contributions of CL to their teaching, is provided. The contributors highlighted tips and suggestions for teachers and provided ideas for developing related lessons/activities.

Before Sections C2–C4, Section C1 provides a detailed case study of my experiences in developing a corpus-based EAP course for university-level students of forestry in the US In the following sections, I present the creation of this course, the specific corpus components, student comments and feedback, and my overall impression of the course. A paper that described this short-term corpus-based lesson and student vs. professional writing comparisons entitled “Developing Research Report Writing Skills Using Corpora” (Friginal, 2013b) was published by the English for Specific Purposes Journal. A conference presentation and paper coauthored with forestry professors Thomas Kolb and Martha Lee, and my corpus linguist colleagues Nicole Tracy-Ventura and Jack Grieve (2007), “Teaching Writing within Forestry,” briefly documented the development of the course, its rationale, and perspectives from forestry professionals (Proceedings from the University Education in Natural Resources Conference 2007, Oregon State University). I am, as readers of my work would expect, strongly recommending the corpus-based approach in similar EAP settings and contexts but also providing a discussion of potential challenges and limitations.

C1.1 CL for an EAP Course: A Case Study

My first set of corpus-based lessons was developed for a university-level writing course for students of forestry. As a writing consultant and a graduate teaching assistant at a School of Forestry (SOF) at NAU, I was first tasked to propose the structure and components of a Writing in Forestry course. The primary goal of the course was to replace the required sophomore-level writing course taught by the English Department with this new one, taught within the School. The course followed the typical structure of an EAP curriculum, emphasizing the need to improve students’ experience and competence in the types of writing used in upper division forestry courses and by professional foresters. I received enthusiastic encouragement and support from SOF faculty, allowing me, as a language and writing expert, to gain more understanding of the writing requirements they have in their courses. I was amazed at the level and rigor of writing expected of undergraduate students in this forestry program. Before the creation of my actual course, my work (and two other former writing consultants) centered on providing informal writing instruction to students and developing and presenting occasional workshops on writing in undergraduate forestry at the School. Several classes required students to seek suggestions or tutoring for improving their writing for specific laboratory assignments. I was pleasantly surprised at the students’ enthusiasm in discussing with me their work, and I had students lined up for my office hours, especially when a major assignment was due. During my course development stage, I produced a draft syllabus and a coursepack of instructional materials that incorporated data from corpora. I visited forestry courses that required written assignments and interviewed faculty about the types and registers of academic writing in their courses. I started collecting various corpora of published, peer-reviewed academic journals (including papers written by forestry professors from the School). The assignments for the course were developed specifically to teach writing skills to junior- and senior-level students.

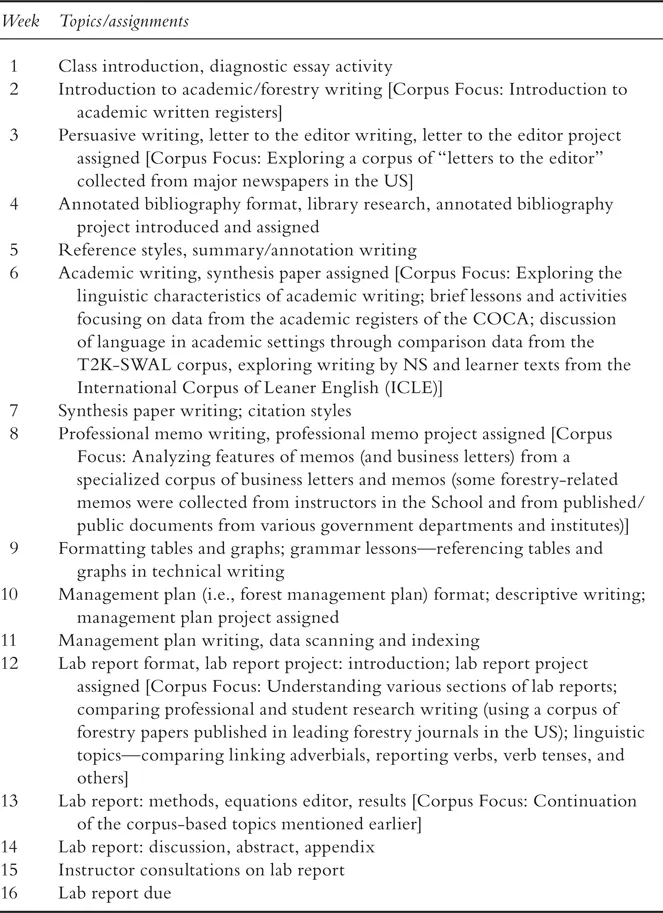

The Writing in Forestry course was approved by the university as a required course in the B.S. in Forestry program. Freshman-level English Composition was a prerequisite, and students took the course in their sophomore year (and before taking a forest measurements class that requires several laboratory-style reports). It was a two-credit course designed to provide a survey and overview of written registers in the professional forestry program and in forestry careers in the US Part of its description included references to “corpus-based approaches” and “corpora and academic and professional writing” (Kolb et al., 2007). Students were introduced to the structure and rhetorical styles of (a) annotated bibliography, (b) technical synthesis papers, (c) laboratory reports, (d) forestry-based memos, (e) professional “opinion pieces,” and (f) selected sections of a forest management plan. The tasks and activities identified for the course were intended to heighten students’ awareness of the written communication component of the professional forestry program and to serve as venues for practice in presenting content information using persuasive, clear, concise, accurate language. Table C1.1 provides a list of weekly topics, highlighting parts that incorporated corpus-based lessons and activities.

TABLE C1.1 Major topics and assignments in the Writing in Forestry course by week

My course started with a diagnostic essay assignment (“Why are you interested in forestry?”) to help me in conducting an initial assessment of each student’s strengths and weaknesses in a more structured academic writing context. The second week introduced students to more specific academic and technical writing in forestry by discussing how forestry and scientific writing may be different from other forms of writing (i.e., register comparison) they have done in the past, including their freshmen English prerequisite course. Empirical fact and data-based argumentation were emphasized for this week’s discussion. Corpus data for comparison and an introduction to CL were provided.

Persuasive writing was the focus of the third week, and I assigned my students to write an approximately 200-word letter to the editor of the local newspaper, expressing their opinion on a forestry-related topic of their choice. The topic had to be current (e.g., forest fires, bark beetle infestation, forest lands thinning concerns) and accessible to the general public. In the fourth week, students were assigned to write an annotated bibliography on a forestry topic of their choice. After choosing a topic, they conducted library research to identify six relevant academic sources (i.e., journal articles, books, technical reports). The sources had to provide different perspectives on the topic and come from credible academic publications. Finally, each source must be cited in the name-year system and be followed by...