eBook - ePub

Managing Religious Diversity in the Workplace

Examples from Around the World

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing Religious Diversity in the Workplace

Examples from Around the World

About this book

Many observers propose the exclusion of all religious related aspects from organizational life, others promote a more tolerant approach of certain practices, symbols and ceremonies, and few commentators highlight the values, diverse religious beliefs and experiences that employees could bring to the organization. Arguments, conclusions and recommendations are often contradictory and inconclusive due to the complexity and dividing nature of religion diversity. In Managing Religious Diversity in the Workplace the editors present a selection of essays, conceptual papers, empirical studies and case studies about how religious diversity and spirituality are managed. The book explores how firms address organizational and managerial challenges deriving from the religion diverse backgrounds of their employees. The different contributions discuss policies and practices, how implicit and unmarked religious norms influence the 'managing' of religious issues in organizations, and what the benefits of a religion diverse workforce are. It also includes contributions which address aspects of spirituality in the workplace, and the role of legal frameworks and their influence on organizations and their policies and practices regarding religion diversity. The perspectives and contributions include a wide range of disciplines by authors from leading academic institutions around the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Managing Religious Diversity in the Workplace by Stefan Gröschl,Regine Bendl in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

This book provides a collection of texts dealing with religious and spiritual perspectives in organizations and societies, as there has been much debate about religious and spiritual diversity in the workplace in many countries around the world. From a secular perspective, religious and spiritual identity as a key characteristic of personal identity has moved into the centre of societal, political and organizational attention. Much of this debate has had negative connotations with the focus often being religious militantism, dogmatic prejudices, uncompromising and excluding attitudes, and religious worshipping practices and ceremonies disrupting organizational life and performance. Often, organizational contexts are considered as ‘religious neutral’ spaces without considering the fact that organizations operate in contexts shaped by religions in general, and often by unmarked and implicit religious norms in particular. Depending on the context, many (mostly secular) observers propose the exclusion of all religious- and spiritual-related aspects from organizational life, others promote a more tolerant approach to certain practices, symbols and ceremonies, and a few commentators highlight the benefits that the values, diverse religious beliefs and experiences of employees could bring to the organization. Arguments, conclusions and recommendations are often contradictive and inconclusive due to the complexity and dividing nature of religious and spiritual diversity and to the different cultural, political and legal contexts.

Our motivation for this book was to collect and present examples of how religious and spiritual diversity is managed in the workplace. In general, we wanted to understand how organizations address organizational and managerial challenges deriving from the religiously diverse backgrounds of their employees (believer/non-believer, spiritual or non-spiritual persons, different religions, and so on). As editors of this book who are working in the field of diversity in management and organizations, not only do we have a great scholarly interest in the topic but believe that scholarly interest goes far beyond the organizational boundaries and the workplace: it is the context and the relational perspective between the micro, meso and macro context (Syed and Özbilin, 2009; Tatli and Özbilgin, 2012; Tatli, Vassilopoulou, Al Ariss, and Özbilgin, 2012) which matters and influences the workplace and organizational practices of managing religion and spirituality. Thus, this collection on Managing Religious Diversity at the Workplace: Examples from Around the World addresses two levels: organizational practices as well as macro socio-political and/or legal perspectives. The chapters provide many organizational examples which address the different religious and spiritual beliefs of employees on the one hand and refer to cultural, socio-political and legal country perspectives on the other hand. The wide range of geographically different contexts covered in the book provide the reader with insights as to how organizational practices differ culturally when it comes to managing the religious and spiritual diversity of employees, and how religion and spirituality (re)produce workplace arrangements.

We have chosen regions as the structuring principle for the book, starting with the North American region, comprising chapters about Canada and the United States. Part II covers Africa, referring to South Africa, Uganda, Tanzania and Algeria. Part III represents the Middle East and Asia with chapters covering the United Arab Emirates, India, the Philippines and Indonesia. Last but not least, Part IV deals with European perspectives from Spain, Belgium and Germany. What all these texts have in common, despite their different cultural, political and legal contexts, is the fact that they show how religion and spirituality are deeply ingrained in organizational, societal and national values, cultures and laws and that they represent discursive elements which shape organizational, societal, legal and national as well as cultural discourse. In detail the chapters of this collection read as follows:

The first part of this book, the North American context, starts with religious and spiritual diversity in the Canadian context. In ‘Accommodations in Religious Matters: Quebec and Canadian Perspectives’, Sylvie St-Onge offers an overview of the state of law and practice in Canadian and Quebec organizations regarding accommodation based on religious grounds. Next, in ‘Accommodating Religious Diversity in the Canadian Workplace: The Hijab Predicament in Quebec and Ontario’, Rana Haq presents two stories of Hijabi women from two Canadian provinces. Haq demonstrates exemplarily why modern, educated, professional women are choosing to wear the hijab of their own free will despite facing challenges in Canadian society and the workplace. The third chapter within the Canadian context, ‘Spirituality Meets Western Medicine: Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre’, written by Kathy Sanderson, covers spiritual aspects of aboriginal/indigenous people. She presents a case study on the Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre which serves as a model of best practice, in which all spiritual and religious beliefs are considered and encouraged in order to include traditional, cultural practices as complementary to mainstream Western medicine based upon the specific needs of the service community. Another North American, but USA-oriented, chapter is ‘Islam in American Organizations: Legal Analysis and Recommendations’ by Bahaudin G. Mujtaba and Frank J. Cavico. In the text, the authors analyse the US civil rights laws prohibiting religious and national origin discrimination, harassment and retaliation against employees in the context of Muslim, Arab and Arab American employees, and provide recommendations to employers on avoiding religious discrimination claims pursuant to US civil rights laws.

The second part of the book marks a shift to the African context and presents the role of spirituality and religion in four different African countries: Nassima Carrim describes how the changes in the socio-political landscape, namely from the Apartheid to the Post-Apartheid era, affected socio-religious developments in the South African context. In ‘Managing Religious Diversity in the South African Workplace’, Carrim focuses on the theoretical component of managing diverse religions, provides legal case studies and presents interview results with Muslim and Hindu female and male mangers. Next, Vincent Bagire and Desiderio Barungi Begumisa show how religious diversity is practised within different institutions in the Ugandian context. In their chapter on ‘Practices of Managing Religious Diversity in Institutions: Lessons from Uganda’, the authors highlight different institutions that have cemented harmony despite religious diversity among members. The next chapter within the African context focuses on Tanzania. In ‘Rethinking Religious Diversity Management in Schools: Experience from Tanzania’, Gabriel Ezekia Nduye explores actions which help to ensure the successful management of religious diversity in the workplace. In his chapter, Nduye uses a case study approach focusing on secondary schools in Tanzania. The last chapter of this part, written by Assya Khiat, Nathalie Montargot and Farid Moukkes, explores human resource (HR) practices and Ramadan in Algeria. In their chapter titled ‘Are There Paths towards a New Social Pact during the Month of Ramadan? The Specific Case of Algerian Companies’, the authors show how Ramadan influences HR practices in Algerian organizations.

In Part III of this collection, which refers to the Middle East and Asia, Celia de Anca explores the role of women in Islamic banking in the United Arab Emirates in her chapter ‘Women in Islamic Banks in the United Arab Emirates: Tradition and Modernity’. For the Indian context, Radha R. Sharma and Rupali Pardasani present a chapter on ‘Management of Religious Diversity by Organizations in India’. The authors discuss the concept of religious diversity in the workplace along with strategies for religious tolerance, and implications for human resources management (HRM) professionals for practising their religion/faith. In the chapter ‘Managing Workplace Diversity of Religious Expressions in the Philippines’, Vivien T. Supangco explores the ways by which organizations manage the diversity of religious expressions in the Philippines. She identifies the various forms of religious expressions in local and multinational companies and examines differences in policies and practices. Next, in the context of Indonesian higher education institutions, Tri Wulida Afrianty, Theodora Issa and John Burgess provide empirical evidence of the relationship between religiosity support usage and employees’ work attitudes and behaviours. In their chapter ‘Work-based Religiosity Support in Indonesia’, the authors come to the conclusion that there is a negative correlation between religiosity support usage and employees’ performance specific to the job requirement in the selected Indonesian higher education context.

Finally, the last part of the book brings the reader to the European context. In the their chapter ‘Religion and Spirituality — the Blind Spot of Business Schools? Empirical Snapshots and Theoretical Reflections’, Wolfgang Mayrhofer and Martin A. Steinbereithner proceed from the assumption that religion and spirituality represent a blind spot for the goals and values of business schools in their daily routines, infrastructure and in their leadership education curricula. In order to address this blind spot, the authors take an exploratory look at two top European Business schools. In the next the chapter on ‘Managing Muslim Employees and Islamic Practices at Work: Exploring Elements Shaping Policies on Religious Practices in Belgian Organizations’, Koen Van Laer aims to advance the understanding of the way organizations approach the management of Islam, Muslim employees and Islamic practices. Based on interviews in three Belgian organizations, this chapter explores how organizations deal with religions at work, especially with the different material and discursive elements that shape, influence or constrain the adoption of polices regarding Islamic practices. ‘Performing Religious Diversity: Atheist, Christian, Muslim and Hindu Interactions in Two German R&D Companies’ is the last chapter discussing the European context. In her text, Jasmin Mahadevan links multiple levels of analysis to reflect on imbalances of power, mainly the intersections between structure and agency. Mahadevan takes a performative stance and explores what people actually do when ‘being religious’ in the workplace, and links the meaning derived from these doings to larger structures, contexts and discourses on religion. The concluding chapter of this collective book focuses on ‘Religious Stimuli in the Workplace and Individual Performance: The Role of Abstract Mindset’, written by Shiva Taghavi. In this conceptual chapter the author highlights the relationship between religious cues in the workplace and the individual’s work behaviour.

This book is the first collection of texts on religious and spiritual organizational practices and the workplace. It contributes to the literature by providing an insight into how religious and spiritual diversity is managed in organizations and societies. As such, it complements the scholarly discourse in Management and Organization Studies on religion and spirituality (for example, Tracey, Phillips, Lounsbury 2014a, and texts published in the Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion).

We believe that this book represents an important milestone in exploring and better understanding religious and spiritual diversity within organizational contexts across national borders. Like Tracey et al. (2014b, p. 5) we assume that the study of spirituality and religion in management and organizational contexts may ‘generate significant novel insights on a range of topics and issues — such as identity, culture and motivation — with clear relevance for organizations of all kinds’. As such, this book represents another piece of moving religious and spiritual perspectives from the margin to the centre of Management and Organization Studies and of unveiling ‘norm’ and ‘otherness’ of spirituality and religion in organizational contexts and the workplace.

References

Tracey, P., Phillips, N. and Lounsbury, M. (2014a). Religion and Organization Theory. Emerald, Bingley.

Tracey, P., Phillips, N. and Lounsbury, M. (2014b). Taking Religion Seriously in the Study of Organizations. In Tracey, P., Phillips, N. and Lounsbury, M. (eds) Religion and Organization Theory. Emerald, Bingley: 3–21

Syed, J. and Özbilgin, M. (2009). ‘A Relational Framework for International Transfer of Diversity Management Practices’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(12): 2435–53.

Tatli, A. and Özbilgin, M.F. (2012). ‘An Emic Approach to Intersectional Study of Diversity at Work: A Bourdieuan Framing’, International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(2): 180–200.

Tatli, A., Vassilopoulou, J., Al Ariss, A. and Özbilgin, M. (2012). ‘The Role of Regulatory and Temporal Context in the Construction of Diversity Discourses: The Case of the UK, France and Germany’, European Journal of Industrial Relations, 18(4): 293–308.

North America

Chapter 2

Accommodations in Religious Matters: Quebec and Canadian Perspectives

Introduction

Over the past few decades, Canada has absorbed a considerable flow of immigrants relative to its population, in contrast to many other Western countries which have sharply curtailed immigration flows. As a result, in Toronto, Canada’s largest metropolis, more than 50 per cent of the population is actually constituted of visible or linguistic ‘minorities’. In Montreal, Canada’s second largest city, more than 50 per cent of the pupils enrolled with the Montreal School Board have at least one parent who was born outside of Canada. One outcome of such large immigration flows is that Canadian society is now increasingly diverse.

This chapter offers an overview of the state of the law and practice in Canadian and Quebec organizations regarding accommodation based on religious grounds. We begin by presenting the exclusionary effect that accommodations are intended to mitigate. We then explain the debate on reasonable accommodations in light of the opposite perspectives that people may adopt. We also look at how Canadian courts define religious beliefs and we explain the State’s obligation of neutrality and its duty to protect freedom of religion. We then illustrate the legal obligation of reasonable accommodation by citing various cases involving religion and the accommodations that have been imposed on or voluntarily adopted by employers. Finally, we explain and illustrate the concept of undue hardship justifying decisions to refuse accommodation.

Under Law, There is Injustice if There are Exclusionary Effects

History and experience have shown that people tend to value other individuals with customs and appearance which resemble their own and to reject, or at best tolerate, those who are perceived as different. The term for this is ethnocentrism or the tendency to prefer one’s own group or culture and to perceive members of other groups or cultures in a less favourable light (Groupe Conseil Continuum, 2005). Ethnocentrism leads to prejudice, which is a preconceived positive or negative opinion about people or things based on certain characteristics. It also leads to stereotypes, whereby people attribute certain behaviours to a person on the grounds of their membership in a group; an example would be presuming an employee’s reaction to a change solely on the basis of their ethnic origin, gender, age and so on. As Banon and Chanlat (2012) point out, ‘the fact that a person has a North African sounding name does not necessarily mean that person is Muslim’. Indeed, many Muslim citizens act no differently than Catholics, Protestants, Jews or non-believers, and indeed even have common values.

All accommodation measures, but particularly those of a religious nature, are a source of social tension and debate in Canada. Such accommodations might be seen as ‘privileges’ that threaten the equality of citizens. However, as we will argue here, these accommodations are in fact a natural consequence of the right to equality; religious minorities have the right to preserve their differences from the majority by being granted accommodations in relation to uniformly applied standards that have an adverse effect on their freedom of religion. There remains a tendency within both workplaces and society at large to equate equality and justice with formal, uniform and equal or identical treatment, without regard for the differences, identities or specific realities of certain groups and their individual members. This occurs regularly, whether during hiring or in the course of employment, such as in the assignment of tasks, work schedules, vacation, disciplinary action, layoffs and so on. According to Brunelle (2008), the strong tendency of unions to negotiate the protection of seniority rights reflects this desire to counter ‘employer arbitrariness’ by urging the employer to treat all employees equally, based on a single, objective criterion that is common to all.

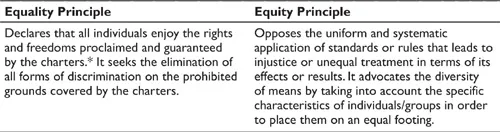

However, as Table 2.1 below shows, an apparently neutral condition of employment that is adopted in good faith for business reasons and that is applicable to all employees can be discriminatory (real injustice) if it has the effect of imposing a disadvantage or penalties on an individual or group that it does not impose on the other individuals (often members of the majority) to whom it may apply. This raises the issue of the distinction between equality and equity. While direct discrimination of the type ‘We don’t hire people belonging to group X’ is clearly illegal, the principle of equity aims to correct indirect discrimination that arises when the uniform application of a rule that appears to be neutral and justified in practice excludes certain individuals because of a specific characteristic (unequal results or effects). For example, the requirement to work every other Saturday or scheduling an exam on a Saturday without offering the possibility of an alternative arrangement is more prejudicial to people who observe the Sabbath than to Christians.

Table 2.1 Equality versus equity principles

* Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms [online], Retrieved on 26 January 2015 from http://www2.publicationsduquebec.gouv.qc.ca/dynamicSearch/telecharge.php?type=2&file=/C_12/C12_A.html; Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms [online], http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/index.html. Both retrieved 26 January 2015.

Discrimination in this context means ‘practices or attitudes that have, whether by design or impact, the effect of limiting an individual’s or a group’s right to the opportunities generally available because of attributed rather than actual characteristics. What is impeding the full development of the potential is not the individual’s capacity but an external barrier that artificial...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Editors’ Biographies

- About the Contributors

- 1 Introduction

- PART I NORTH AMERICA

- PART II AFRICA

- PART III MIDDLE EAST AND ASIA

- PART IV EUROPE

- Index