![]()

1

Facts and Myths about Bilingualism

INTRODUCTION

Bilingualism is a fact of life for the vast majority of the world’s populations. It is estimated that as much as two-thirds of the people in the world are bilingual (Crystal, 2003). There are anywhere between 6,000 and 7,000 languages spoken in the world today and only about 190 countries in which to house them, which suggests how widespread bilingualism (or multilingualism) must be. Bilingualism involving two or more languages is quite common in many of the historically multilingual societies of Africa and Asia. For example, some 25 languages are spoken in South Africa and 20 in Mozambique (Kamwangamalu, 2006). Bilingualism is an integral part of the cultural fabric of India where 216 languages have at least 10,000 speakers each and 24 of them are recognized by the national constitution (Bhatia & Ritchie, 2006b).

Pandit (1977), as cited in Gargesh (2006: 91), provides an apt description of the functional multilingualism of an Indian businessman living in a suburb of Bombay (Mumbai). His mother tongue and home language is a dialect of Gujarati; in the market he uses a familiar variety of Marathi, the state language; at the railway station he speaks Hindi, the pan-Indian lingua franca (a common language used by speakers of different mother tongues); his language of work is Kachhi, the code of the spice trade; in the evening he watches a film in Hindi or in English and listens to a cricket match commentary on the radio in English. As this example illustrates, a whole range of languages are available to Indians, who choose each language purposefully to perform particular social functions.

Even in many of the world’s so-called “monolingual” nations, one can find substantial numbers of bilingual individuals and communities. For instance, 63.2 million Americans—or one in five Americans—age five and older, speak a language other than English at home (Camarota & Ziegler, 2015). Germany and France have the largest Muslim populations among European Union member countries—4.8 million and 4.7 million respectively (Pew Research Center, 2016), and 16.4 million people living in Germany (over 20% of the total population) have an immigrant background (Facts about Germany, 2017). Many people in officially monolingual countries know someone who is bilingual even if they may not use two or more languages regularly.

Although there are more bilingual than monolingual people in the world, bilingualism has traditionally been treated as a special case or a deviation from the monolingual norm (Romaine, 1995: 8). Most linguistic research has tended to focus on monolinguals and has treated bilinguals as exceptions. For instance, Chomsky’s (1965: 3) theory of grammar is concerned primarily with “an ideal speaker-listener, in a completely homogeneous speech community, who knows its language perfectly.” Given the emphasis on describing the linguistic competence of the ideal monolingual speaker, bilingualism has necessarily been regarded as problematic, an impure form of communication by people who do not seem to know either language fully.

One of the ways in which people display their bilingual abilities is through code-switching, a change of language within a conversation, usually when bilinguals are in the company of other bilinguals. Code-switching is perhaps the most obvious indication of one’s bilingual abilities, since very few bilinguals keep their two languages completely separate (Gardner-Chloros, 2009). However, monolinguals who hear bilinguals code-switch often have negative attitudes toward code-switching and think that it represents a lack of mastery of either language. Pejorative names such as “Chinglish” (Chinese-English), “Konglish” (Korean-English), and “Franglais” (French-English) are often used to refer to the mixed speech of bilinguals, and bilinguals themselves may feel embarrassed about their code-switching and attribute it to careless language habits or laziness (Grosjean, 1982: 148). However, a great deal of research in the past few decades has shown that code-switching, far from being a communicative deficit, is a valuable linguistic strategy (see Chapter 6 for a review of the research on code-switching).

Strictly speaking, it would be difficult to find someone who thinks bilingualism is downright bad. After all, to most people, having proficiency in two or more languages is considered a desirable attribute—one can reasonably argue that knowing two languages is better than knowing just one. Indeed many people think that bilingualism is a sign of intellectual prowess and sophistication—those who have competence in several languages are often regarded with envy and admiration. However, attitudes toward bilingualism and bilingual people vary widely depending on who the bilingual is and the circumstances of his/her bilingualism. For example, while the bilingualism of a Haitian immigrant to the U.S. may be frowned upon as evidence that he has not yet fully integrated into mainstream American society, the bilingual abilities of a native English-speaking Anglo American who has learned French as a foreign language may be prized as a valuable asset.

In this book, I discuss the social contexts that make certain kinds of bilingualism desirable and others not so desirable, and how these influence language and educational policies at various levels. The languages involved in any bilingual situation almost never have the same status—one variety is perceived as having greater prestige and value than another. We will explore how these unequal perceptions shape and color the ways in which people—bilinguals and monolinguals alike—identify themselves and others. We will also see how parents’ and teachers’ educational decisions are driven by larger sociopolitical forces as well as by personal motivations for achieving bilingualism. I will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of different models of bilingual education programs and research-based best practices for promoting bilingual development in children from both majority language and minority language backgrounds. Throughout the book, I aim to show that bilingualism is a resource to be cultivated for all kinds of populations, not a problem to be overcome.

OUT OF THE MOUTHS OF BILINGUALS 1.1 Multilingualism as the Norm in Malawi | |

“My father is Tonga by tribe and he has always spoken to me in Chitonga, Chitumbuka and English, with a bit of Chicheŵa. My mother is Sena by tribe, but she has always spoken to me in Chitumbuka, Chicheŵa and English, with a bit of Chitonga … I acquired Chitonga, Chitumbuka and Chicheŵa as mother tongues simultaneously, and English as a second language.”

(Kamanga, 2009: 115)

At the heart of much debate on language in schools and society are certain myths about bilingual processes and people. In the following, I disprove five such myths by providing the relevant facts and research evidence:

Myth #1: | A bilingual is fully proficient in two languages. |

Myth #2: | Immigrants are reluctant to learn English. |

Myth #3: | Children need early exposure to a second language if they are to learn it successfully. |

Myth #4: | Immigrant parents should speak the societal language to their children at home to help them succeed in school. |

Myth #5: | High dropout rates of Hispanic students in the U.S. demonstrate the failure of bilingual education. |

The following discussion of the myths and facts about bilingualism introduces the reader to some of the major topics that are covered in this book.

MYTH #1: A BILINGUAL IS FULLY PROFICIENT IN TWO LANGUAGES

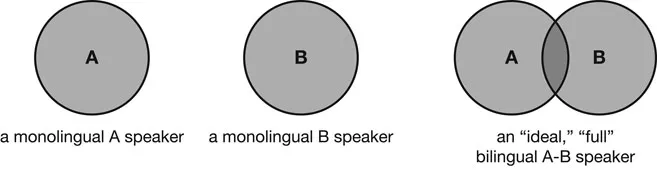

One of the most common myths about bilingualism is the view that a bilingual is completely fluent in two languages. It is often assumed that “true” bilinguals are those who are equally proficient in their two languages, with competence in both languages comparable to those of monolinguals of those languages. Figure 1.1, which illustrates this myth, shows three individuals—a monolingual speaker of language A, a monolingual speaker of language B, and an “ideal” bilingual speaker of languages A and B. This is a crude and oversimplified diagram that does not accurately depict the changing needs for a bilingual’s two languages in different situations with different interlocutors, but it nonetheless illustrates my point. Notice that the size of the circles (which indicate the level of proficiency in each language) is the same for monolingual A and monolingual B speakers as well as for the bilingual A-B speaker.

In reality, however, bilinguals will rarely have balanced proficiency in their two languages. Terms such as “full” bilingual and “balanced” bilingual represent idealized concepts that do not characterize the great majority of the world’s bilinguals. Rarely will any bilingual be equally proficient in speaking, listening, reading, and writing both languages across all different situations and domains. In other words, a bilingual is not the sum of two monolinguals. However, the monolingual view of bilingualism is so entrenched in popular and scholarly thinking that bilinguals themselves may apologize to monolinguals for not speaking their language as well as do monolinguals, thus accepting and reinforcing the myth.

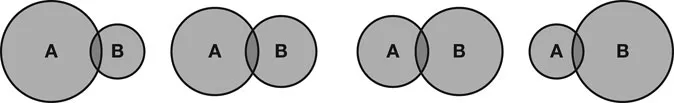

Most bilinguals in the world look more like those in Figure 1.2, which shows four A-B bilinguals. Notice that the relative sizes of the circles are different in each, indicating that the bilinguals have different proficiencies in the two languages. The bilinguals’ proficiency in each of the two languages may be lower than that of monolingual speakers of each language, but taken together, the bilinguals’ two languages are bigger than a monolingual’s only language in terms of vocabulary, syntax, and range of expression. Most bilinguals have different proficiencies in two languages because the two languages are often learned under different conditions for a range of purposes, and are used in a variety of situations with different people.

FIGURE 1.1 A Mythical View of the “Ideal” or “Full” Bilingual

FIGURE 1.2 More Realistic Conceptions of Bilinguals

As an illustration, I will describe my experiences as a bilingual. I am a native speaker of Korean who started learning English as a second language at the age of 13 when I moved to the U.S. as an immigrant. As a newcomer student in a local junior high school, I had to skip one class each day to go to a separate ESL class where I learned English grammar and pronunciation with other immigrant students. Learning school subjects in English was enormously difficult, and I remember often coming home frustrated and exhausted from having to hear, speak, and read English all day. I spoke in Korean at home with my family but slowly my two younger brothers and I included bits of English in our otherwise Korean interactions. We watched TV programming in English, made friends with kids from other countries in our ethnically diverse neighborhood in New York City, and tried to keep up with schoolwork in English.

While my English skills developed both academically and socially throughout high school and college, my Korean skills stagnated since I used it only at home. I would say that my current reading and writing skills in Korean are at about an eighth-grade level which is when I stopped being schooled in Korean. Although I have no trouble communicating informally in Korean, I find giving an academic lecture in Korean quite challenging because I never learned the advanced discipline-specific vocabulary and syntax in Korean to be able to do so. I am married to a Korean American and we have two American-born sons who, despite our many efforts to teach them Korean, are mostly English speaking. Spousal communication at our home is a mixture of Korean and English but we find ourselves speaking more and more English as our children grow up. I do almost all of my reading and writing in English now and rarely pick up a Korean newspaper. Since the uses for my two languages are very compartmentalized (English for work, Korean for home and ethnic community), I do not have the same proficiencies in both languages. Overall, my bilingualism has been an evolving phenomenon and is continually changing with shifting circumstances and communicative needs in my life. The same is true for many bilinguals in the world.

FIGURE 1.3 What a “Semilingual” Child Might Look Like

In educational circles, the term semilingual has been used to describe bilingual students who appear to lack proficiency in both languages (Martin-Jones & Romaine, 1986). Figure 1.3 shows what a semilingual child might look like. Compared to the “ideal” or “full” bilingual in Figure 1.1, a semilingual falls short in both languages. Before the 1960s, there was an overwhelming number of studies that highlighted the negative effects of bilingualism on children (Romaine, 1995: 107). Observers noted many problems with language development of bilingual children, such as restricted vocabularies, limited grammatical structures, unusual word order, errors in morphology, hesitations, stuttering, and so on. Some have even argued that bilingualism could impair the child’s intelligence and lead to split personalities.

Valadez, MacSwan, and Martínez (2000) quote a 1996 Los Angeles Times article which reported that in the schools of the Los Angeles Unified School District there were 6,800 immigrant students who have been labeled “non-nons” or “clinically disfluent,” that is, children who allegedly do not know English, Spanish, or any other language. The district’s educational response was to place these children in separate classrooms and provide them with intensive language instruction. Supposing that this many students could not all be linguistically deficient, Valadez et al. (2000) systematically compared the oral language proficiencies of children who were labeled as “clinically disfluent” by the school psychologist and children who were identified as having “normal” or “high” ability. They found that the group of children labeled “clinically disfluent” or “semilingual” did not have an impoverished knowledge of morphology, nor did they make frequent errors in syntax. Contrary to the school evaluations, these students were not inexpressive. In fact, the authors found that the “semilingua...