- 1,842 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

EU Shipping Law

About this book

A previous winner of the Comité Maritime International's Albert Lilar Prize for the best shipping law book worldwide, EU Shipping Law is the foremost reference work for professionals in this area. This third edition has been completely revised to include developments in the competition/antitrust regime, new safety and environmental rules, and rules governing security and ports. It includes detailed commentary and analysis of almost every aspect of EU law as it affects shipping.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access EU Shipping Law by Vincent Power in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

A. SCOPE OF THIS BOOK

1.001 This book is an introduction to several aspects of the law of the European Union (“EU”)1 as it relates to shipping or maritime transport.2 Instead of being a general textbook on EU law, this book takes a specialist approach to EU law by identifying and examining many of the aspects of EU law most relevant to shipping.3 Given the breadth of the topic, the book concentrates on issues most relevant to shipping because almost any area of EU law is potentially relevant to the sector.

1.002 EU shipping law is an important topic because, as was stated in the Athens Declaration of 7 May 2014 (more formally entitled Mid-Term Review of the EU’s Maritime Transport Policy until 2018 and Outlook to 2020),

“the EU is highly dependent on maritime transport4 both for its internal and external trade since 75% of the Union’s imports and exports and 37% of the internal trade transit through seaports5 and that shipping is a highly mobile industry facing increasingly fierce competition from third countries”.6

The EU is now a major source of shipping law.

B. THE EUROPEAN UNION

Introduction

1.003 Before introducing EU shipping law, it is useful to provide some background on the EU generally. The EU is the most sophisticated international organisation in the world. It comprises 28 Member States7 who have ceded some elements of their sovereignty to create the EU. The conduct of these Member States along with other participants in the sector such as shipping companies, ports and seafarers can now be controlled in certain circumstances by the EU; in return, however, they have rights and opportunities which they would not otherwise possess (e.g. the right to establish businesses or work in other Member States on an equal footing with nationals in those Member States).8

Evolution of the European Union

1.004 The EU is the successor of the European Economic Community9 (“EEC”) which was founded in 1957. The EEC became the European Community (“EC”) in the 1990s and is now the EU.

1.005 The EU is the product of the phenomenon known as European Integration. After the ravages of the Second World War in Europe, a plan was devised known as the Schuman Plan10 advocating that France and Germany should form closer links between the two countries (who had fought each other three times over the previous 70 years) to place the principal weapons of war at the time (namely, coal and steel) under the supervision of a common authority11 and in a common market12 so as to minimise the risk of war between them and in Europe generally. This plan led to the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community (“ECSC”) in 1952. While the original plan was just to involve France and Germany, four other States (i.e. Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) also participated in the ECSC. The ECSC was successful and it was quickly realised that the successes in the context of coal and steel could be extended to other economic sectors (i.e. to the economy generally including the shipping sector). This led to the establishment of the EEC and the European Atomic Energy Community (“EAEC”) in 1957.

1.006 The ECSC had come into existence in 1952 with six Member States.13 These six States then formed the EEC and EAEC in 1957.14 In 1973, the membership of the three Communities (i.e. the ECSC, EEC and EAEC) grew to nine States;15 there were ten States when Greece acceded in 1981; in 1986, two Iberian States16 joined; three States joined in 1995;17 ten States joined in 2004 in the largest accession ever;18 two further States joined in 2007;19 and one State joined in 2013.20 Today, there are therefore 28 Member States in the EU: Austria; Belgium; Bulgaria; Croatia, Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; France; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Ireland; Italy; Latvia; Lithuania; Luxembourg; Malta; Netherlands; Poland; Portugal; Romania; Slovakia; Slovenia; Spain; Sweden; and United Kingdom. Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iceland, Kosovo, Montenegro, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine are among the potential future Member States.

1.007 The EU is an evolving phenomenon. Generally speaking, it is expanding, rather than contracting, in terms of membership, competence and activities. It has experienced dynamic development punctuated by occasional stagnation but rarely permanent reversal. It began life in the 1950s as a group of three intergovernmental organisations21 and is now an economic, monetary22 and political union23 of global significance. There were times in the 1970s and 1980s when it suffered degrees of paralysis. In recent years, it suffered a crisis related to the euro currency and the Economic and Monetary Union (“EMU”) but it has survived the crisis. It will face further challenges in the future including, at the time of writing, a crisis over migration and the possible exit from the EU by the United Kingdom. However, the EU is now playing a significant role in world affairs as a collective unit having diplomatic relations and standing around the world. The EU developed a special relationship with some neighbouring States by the formation of the European Economic Area (“EEA”) with effect from 1994 and today those States are Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein. Equally, the EU is forming relationships in different spheres throughout the world. The EU, as a separate entity from its Member States, has the power to conclude certain types of international agreements within its sphere of competence and has concluded many such agreements to date. Ultimately, the EU evolves and acquires new powers because its Member States confer new powers upon it.

The EU is the world’s largest economic bloc

1.008 The EU is the world’s largest economic bloc. There is no doubt that the EU has long been forced, in the words of the European Parliament many years ago, to “speak with one voice and to adopt a common position”.24 It represents around 7% of the world’s population, constitutes the top trading partner for 80 countries around the world but about 23% of the world’s nominal gross domestic product (“GDP”) and represents 16% of global exports and imports. It is the world’s largest exporter of goods25 and the second largest importer.26

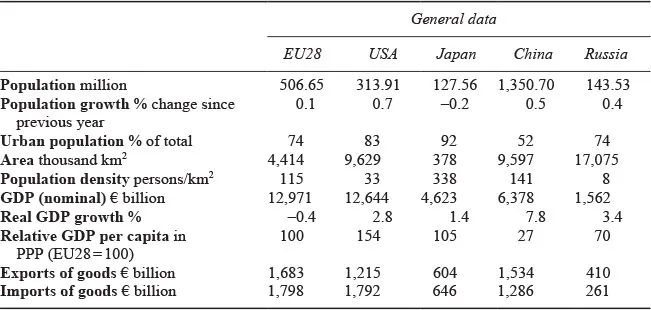

1.009 The EU’s Statistical Pocketbook 2017 (the most recent available at the time of writing) puts the EU into a global context (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Comparison EU28 – World

Source: Eurostat, World Bank. Relative GDP per capita and currency conversion rates: own calculations based on World Bank data (2012 data used).

Notes

EU28: area, population: including French overseas departments.

EU28: trade: only extra-EU trade.

EU28: area, population: including French overseas departments.

EU28: trade: only extra-EU trade.

Population

1.010 The EU has a population of just over 500 million. It is therefore the third most populous area in the world after China and India. It is more populous than the USA. The three largest Member States in terms of population are Germany (with 81 million people), France (with 66 million people) and the UK (with 64 million people).27 Its Member States represent a range in terms of population from these three large States to States such as Cyprus and Malta with relatively small populations.

The internal market

1.011 One of the core elements of the EU is the notion of the internal market which means that goods and services must be able to move freely within the EU (subject to very limited exceptions, i.e. the “internal market”) and there would be a common external tariff vis-à-vis the rest of the world (i.e. the customs union). This internal market (or common market) has been at the heart of the EU project since the 1950s. Initially, the notion was that States were less likely to go to war if they traded intensively with each other but now there is an inherent economic merit in having an internal market apart altogether from the prevention of war because of the efficiencies created by a large “home” market (i.e. the whole of the EU).

1.012 Establishing an internal market has always been difficult. Some Member States (or, sometimes some sectoral interests within those States) have sought to erect barriers to trade.28 While progress was made in the 1960s, the completion of the internal market had still not been achieved by the early 1980s. So a programme, the Internal Market Programme (known colloquially as the “1992 Programme” because the aim was to complete the internal market programme by the end of 1992) was devised by the Commission in 1985. The plan devised involved 279 measures to integrate the national markets of the Member States into one single or internal market. The internal market programme achieved a great dea...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Detailed Table of Contents

- Preface

- Table of abbreviations

- Table of cases

- Table of legislation

- CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 2: A COMMERCIAL OVERVIEW OF SHIPPING IN THE EUROPEAN UNION

- CHAPTER 3: AN OVERVIEW OF THE EUROPEAN UNION AND EUROPEAN UNION LAW

- CHAPTER 4: AN OVERVIEW OF EUROPEAN UNION TRANSPORT LAW

- CHAPTER 5: THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF EUROPEAN UNION SHIPPING LAW

- CHAPTER 6: EUROPEAN UNION LAW RELATING TO THE FREEDOM OF ESTABLISHMENT OF SHIPPING BUSINESSES AND THE REGISTRATION OF SHIPS

- CHAPTER 7: EUROPEAN UNION LAW RELATING TO FREEDOM TO SUPPLY SERVICES: INTERNATIONAL SERVICES; CABOTAGE SERVICES; AND SHIPPING SERVICES GENERALLY

- CHAPTER 8: EUROPEAN UNION LAW RELATING TO EMPLOYMENT IN THE SHIPPING SECTOR

- CHAPTER 9: INTRODUCTION TO LINER CONFERENCES: THE CONCEPT OF LINER CONFERENCES AND THE UNITED NATIONS CODE ON LINER CONFERENCES AND THE UNITED NATIONS LINER CODE

- CHAPTER 10: AN OVERVIEW OF EUROPEAN UNION COMPETITION LAW GENERALLY AND HOW IT APPLIES TO THE SHIPPING SECTOR GENERALLY

- CHAPTER 11: EUROPEAN UNION COMPETITION LAW: THE OLD REGIME RELATING TO SHIPPING – REGULATION 4056/86

- CHAPTER 12: EUROPEAN UNION COMPETITION LAW: THE NEW REGIME RELATING TO SHIPPING – REGULATION 1419/2006

- CHAPTER 13: EUROPEAN UNION COMPETITION LAW: PORTS

- CHAPTER 14: EUROPEAN UNION COMPETITION LAW: CONSORTIA

- CHAPTER 15: EUROPEAN UNION STATE AID LAW: SHIPPING AND PORTS

- CHAPTER 16: EUROPEAN UNION MERGER CONTROL: SHIPPING, PORTS AND SHIPBUILDING

- CHAPTER 17: REGULATION 4057/86: DUMPING OF SHIPPING SERVICES AND THE UNFAIR PRICING OF SHIPPING SERVICES

- CHAPTER 18: REGULATION 4058/86: CO-ORDINATED ACTION TO SAFEGUARD FREE ACCESS TO CARGOES IN OCEAN TRADE

- CHAPTER 19: EUROPEAN UNION LAW RELATING TO THE MARITIME ENVIRONMENT: INTRODUCTION; EUROPEAN UNION MEASURES RELATING TO THE MARITIME ENVIRONMENT GENERALLY; AND PENALTIES FOR INFRINGEMENTS

- CHAPTER 20: EUROPEAN UNION LAW RELATING TO THE MARITIME ENVIRONMENT: ORGANOTIN

- CHAPTER 21: EUROPEAN UNION LAW RELATING TO MARITIME ENVIRONMENT: THE HAZARDOUS AND NOXIOUS SUBSTANCES BY SEA CONVENTION

- CHAPTER 22: EUROPEAN UNION LAW RELATING TO SHIPBUILDING

- CHAPTER 23: EUROPEAN UNION LAW RELATING TO SHIP REPAIR

- CHAPTER 24: EUROPEAN UNION LAW RELATING TO SHIP DISMANTLING AND RECYCLING

- CHAPTER 25: EUROPEAN UNION EXTERNAL RELATIONS LAW AND SHIPPING

- CHAPTER 26: MARITIME SAFETY: INTRODUCTION AND EUROPEAN UNION MEASURES RELATING TO MARITIME SAFETY GENERALLY

- CHAPTER 27: MARITIME SAFETY: THE EUROPEAN MARITIME SAFETY AGENCY

- CHAPTER 28: MARITIME SAFETY: PORT STATE CONTROL

- CHAPTER 29: MARITIME SAFETY: SHIP INSPECTION AND SURVEY ORGANISATIONS

- CHAPTER 30: MARITIME SAFETY: CASUALTY AND ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION

- CHAPTER 31: MARITIME SAFETY: MINIMUM TRAINING OF SEAFARERS

- CHAPTER 32: MARITIME SAFETY: MINIMUM SAFETY AND HEALTH REQUIREMENTS FOR IMPROVED MEDICAL TREATMENT ON BOARD VESSELS

- CHAPTER 33: MARITIME SAFETY: INTERNATIONAL SAFETY MANAGEMENT CODE FOR THE SAFE OPERATION OF SHIPS AND FOR POLLUTION PREVENTION

- CHAPTER 34: MARITIME SAFETY: FERRIES AND RO-RO VESSELS

- CHAPTER 35: MARITIME SAFETY: ORGANISATION OF WORKING TIME OF SEAFARERS

- CHAPTER 36: MARITIME SAFETY: MARITIME LABOUR CONVENTION 2006

- CHAPTER 37: MARITIME SAFETY: MARINE EQUIPMENT

- CHAPTER 38: PIRACY

- CHAPTER 39: NAVIGATION

- CHAPTER 40: PILOTAGE

- CHAPTER 41: SHORT SEA SHIPPING

- CHAPTER 42: SECURITY: SHIPS AND PORTS

- CHAPTER 43: PORTS: GENERALLY AND THE PORT SERVICES REGULATION 2017/352

- CHAPTER 44: PORTS: REPORTING FORMALITIES FOR SHIPS IN EUROPEAN UNION PORTS: DIRECTIVE 2010/65

- CHAPTER 45: PORTS: ELECTRICITY FOR SHIPS IN PORTS

- CHAPTER 46: CARRIAGE OF GOODS AND PASSENGERS

- CHAPTER 47: EUROPEAN UNION LAW AND SHIPPING LITIGATION: THE “BRUSSELS I” REGULATION

- CHAPTER 48: BREXIT

- CHAPTER 49: CONCLUSIONS

- Index