This book is available to read until 2nd June, 2026

- 330 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 2 Jun |Learn more

About this book

Many 21st century operations are characterised by teams of workers dealing with significant risks and complex technology, in competitive, commercially-driven environments. Informed managers in such sectors have realised the necessity of understanding the human dimension to their operations if they hope to improve production and safety performance. While organisational safety culture is a key determinant of workplace safety, it is also essential to focus on the non-technical skills of the system operators based at the 'sharp end' of the organisation. These skills are the cognitive and social skills required for efficient and safe operations, often termed Crew Resource Management (CRM) skills. In industries such as civil aviation, it has long been appreciated that the majority of accidents could have been prevented if better non-technical skills had been demonstrated by personnel operating and maintaining the system. As a result, the aviation industry has pioneered the development of CRM training. Many other organisations are now introducing non-technical skills training, most notably within the healthcare sector. Safety at the Sharp End is a general guide to the theory and practice of non-technical skills for safety. It covers the identification, training and evaluation of non-technical skills and has been written for use by individuals who are studying or training these skills on CRM and other safety or human factors courses. The material is also suitable for undergraduate and post-experience students studying human factors or industrial safety programmes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Safety at the Sharp End by Rhona Flin,Paul O'Connor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Human Resource Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

When things go wrong in high-risk organisations, the consequences can result in damage to humans, equipment and the environment. Significant levels of protection and redundancy are built into modern technical systems, but as the hardware and software have become increasingly reliable, the human contribution to accidents has become ever more apparent. Analyses in a number of industrial sectors have indicated that up to 80% of accident causes can be attributed to human factors (Helmreich, 2000; Reason, 1990; Wagenaar and Groenweg, 1987). This means that managers also need to understand the human dimension to their operations, especially the behaviour of those working on safety-critical tasks – the ‘sharp end’ of an organisation. Psychologists have long been interested in the factors that enhance workers’ performance and minimise error rates (Munsterberg, 1913). We know that human error cannot be eliminated, but efforts can be made to minimise, catch and mitigate errors by ensuring that people have appropriate non-technical skills to cope with the risks and demands of their work.

Non-technical skills are the cognitive and social skills that complement workers’ technical skills (Flin et al., 2003). The definition of non-technical skills used to underpin this book is ‘the cognitive, social and personal resource skills that complement technical skills, and contribute to safe and efficient task performance’. They are not new or mysterious skills but are essentially what the best practitioners do in order to achieve consistently high performance and what the rest of us do ‘on a good day’. This book describes the basic non-technical skills and explains why they are important for safe and efficient performance in a range of high-risk work settings from industry, health care, military and emergency services.

The seven skills we discuss are:

• situation awareness (attention to the work environment)

• decision-making

• communication

• teamwork

• leadership

• managing stress

• coping with fatigue.

This skills approach provides a set of established constructs and a common vocabulary for learning about the important behaviours that influence safe and efficient task execution. Methods of identifying, training and assessing key non-technical skills for particular occupations are outlined in the chapters to follow. The skills listed above are required across a range of settings. Much of the background material is drawn from the aviation industry but our aim is to demonstrate why these nontechnical skills are critical for many different tasks, from operating a control room on a power plant, to operating on a surgical patient. Human behaviour is remarkably similar across all kinds of workplaces.

Before examining the non-technical skills, it should be emphasised that this focus on workers’ behaviours is only one component of an effective safety management strategy. Organisational safety is influenced by regulatory and commercial pressures, the working environment and management demands. So, while this book concentrates on the skills of those operating the system, it is acknowledged that their behaviour is influenced by the conditions they work in and by the behaviours of others, particularly those in managerial positions (Flin, 2003; Hopkins, 2000).

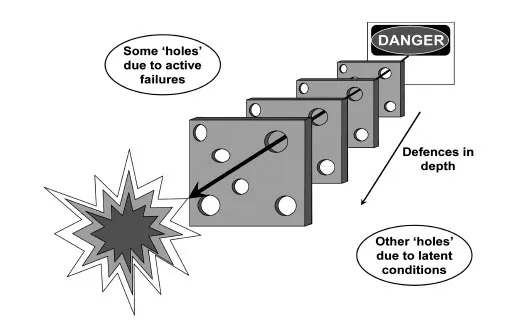

As Reason (1997) illustrated in his ‘Swiss Cheese’ model (see Figure 1.1), accidents are usually caused by a sequence of flaws in an organisation’s defences. These can be attributed to a combination of errors and violations by the operational staff (active failures) and the latent unsafe conditions (‘resident pathogens’) in the work system that are created by managers, designers, engineers and others.

Figure 1.1 An accident trajectory passing through corresponding holes in the layers of organizational defences (Reason, 1997, Fig 1.5)

Reprinted with permission of Ashgate.

The ‘front line’ personnel represent the last line of protection of the system’s defences. They are not only responsible for the active failures that can contribute to losses and injuries, but more importantly, they regularly catch and correct their own and others’ errors. Helmreich et al.’s (2003) observations on aircraft flight decks showed that airline pilots make about two errors per flight segment, but that most of these are caught and corrected by the air crew themselves. Moreover, front-line staff can also recognise and remedy technical malfunctions and can cope with a wide variety of risky conditions. Therefore, while human error is inevitable and pervasive, as Reason (1997) pointed out, humans can also be heroes by providing the essential resilience and expertise to enable the smooth operation of imperfect technical systems in threatening environments.

We begin by describing how a series of puzzling aircraft accidents in the 1970s led to the recognition of the importance of non-technical skills in aviation. This is followed by an account of how these skills have since become a focus of attention in other work settings.

Non-technical accidents in aviation and beyond

Thirty years ago, a series of major aviation accidents, without primary technical cause, forced investigators to look for other contributing factors. The best known of these events is the Tenerife crash in 1977, when two jumbo jets crashed on an airport runway, as described below.

Box 1.1 Tenerife Airport Disaster

At 17:06 on 27 March 1977, two Boeing 747 aircraft collided on the runway of Los Rodeos airport on the island of Tenerife. The jets were Pan Am flight 1736 en route to Las Palmas from Los Angeles via New York and KLM flight 4805 from Amsterdam, also heading for Las Palmas. Both had been diverted to Tenerife because of a terrorist incident on Las Palmas. After several hours, the airport at Las Palmas re-opened and the planes prepared for departure in the congested (due to re-routed aircraft), and now foggy, Los Rodeos airport. The KLM plane taxied to the end of the runway and was waiting for air traffic control (ATC) clearance. The Pan Am plane was instructed to taxi on the runway and then to exit onto another taxiway. The KLM plane was now given its ATC clearance for the route it was to fly – but not its clearance to begin take-off. The KLM captain apparently mistook this message for a take-off clearance, released the brakes, and despite the co-pilot saying something, he proceeded to accelerate his plane down the runway. Due to the fog, the KLM crew could not see the Pan Am 747 taxiing ahead of them. Neither jet could be seen by the control tower and there was no runway radar system. The KLM flight deck engineer, on hearing a radio call from the Pan Am jet, expressed his concern that the US aircraft might not be clear of the runway, but was over-ruled by his captain. Ten seconds before collision, the Pan Am crew noticed the approaching KLM plane but it was too late for them to manoeuvre their plane off the runway. All 234 passengers and 14 crew on the KLM plane and 335 of 396 people on the Pan Am plane were killed.

Analyses of the accident revealed problems relating to communication with ATC, team co-ordination, decision-making, fatigue and leadership behaviours.

See Weick (1991) and Box 5.4. for further details.

This was not an isolated incident. Other aircraft accidents had happened which, like the Tenerife crash, did not have primary technical failures. United Airlines suffered a sequence of crashes in the late 1970s, also attributed to what was now being called ‘pilot error’ rather than technical faults. Due to growing concern, an aviation industry conference was held at NASA in 1979 bringing together psychologists and airline pilots to discuss how to identify and manage the human factors contributing to accidents. The aviation industry was fortunate to have one invaluable source of information, namely the cockpit voice recorders that had been built into modern jet aircraft (CAA, 2006). They revealed what the flight deck crew were saying in the minutes before and during these accidents. Analysis of these conversations suggested failures in leadership, poor team co-ordination, communication breakdowns, lack of assertiveness, inattention, inadequate decision-making and personal limitations, usually relating to stress and fatigue (Beaty, 1995; Wiener et al., 1993).

Accidents involving failures in non-technical skills are certainly not unique to the aviation industry. Table 1.1 gives a sample of such events with failures in non-technical skills at the ‘sharp’ or operational end of an organisation. In two of the world’s most serious nuclear power plant incidents, Chernobyl (Reason, 1987) and Three Mile Island (NRC, 1980), operator error relating to loss of situation awareness and flawed decisio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1 introduction

- 2 Situation Awareness

- 3 Decision-Making

- 4 Communication

- 5 Team Working

- 6 Leadership

- 7 Managing Stress

- 8 Coping with Fatigue

- 9 Identifying Non-Technical Skills

- 10 Training Methods for Non-Technical Skills

- 11 Assessing Non-Technical Skills

- Index