1 Competing in the creative and cultural industries

The strategic way

Interviewing a manager for a connected research project, we were struck by a phrase that he used to describe his organization’s operations in a particular market. He said he was not concerned about the other firms in the sector because his organization was competing ‘unfairly in it’. He did not, of course, mean that his organization used unethical or illegal practices. What he meant was that other firms simply could not compete with them because they did not have the relationships and resources his organization had. The ‘unfair’ part of it was that the other organizations did not stand a chance.

Making it difficult or impossible to compete with you is another way of saying that your organization is looking to create a strategic advantage. Put this way, strategy is the creation of competitive conditions that favour your organization and give it some kind of ‘unfair’ advantage over its rivals. The task of organizations in the CCI is therefore not necessarily to work out how to win a competition, but how to prevent others from being able to compete with you. The difference is subtle, but important.

This chapter will discuss this key attitude towards competition by setting out what strategy means, discussing the importance of being strategic in the CCI and identifying what can prevent organizations from seeking a strategy that will give them a competitive advantage. The chapter will conclude with a schema to divide the various sectors that make up the CCI into three analytical groups. As well as framing the kinds of challenges the firms in each group face, this will also help draw links between the competitive pressures facing these firms and reveal how lessons from one sector or organization may be transferred to another.

What exactly is a strategy?

Competing strategically requires that managers design how their organization works to produce something that is valued by customers in as effective and efficient a way as possible, the general objective being that sufficient customers buy products and services at a price that produces the desired profit level necessary to enable re-investment in the organization and the distribution of rewards for its stakeholders (including customers). It is about deliberately making choices – choices that sum into the purpose and strategy of the organization. These decisions are based on the organization’s resources, the assets it owns and the capabilities of its people, the sector it operates in, the customers it competes for and the relationships it has with suppliers, partners, local institutions and government bodies (Grant, 1991). What capabilities do we want to have? Do we want to be flexible, fast, radical or reliable? How shall we organize people in the organization, in tasks, functional specialisms, projects, hierarchies? What product/service benefits will we offer customers? What needs are we satisfying anyway and at what price? Which customers shall we target, which markets shall we enter or pull out of?

What makes answering these questions so problematic is not that they are particularly difficult or involve complex analysis. They may strike you as the standard questions answered by managers as they work out how to deal with the competition. What is difficult about answering these questions and thereby beginning to craft a strategy is that the decision involves deciding what not to do, as well as what to do (Porter, 1996). If the actions and orientations of the firm are not discriminative then there is the probability that the organization’s ‘strategy’ is what could be termed an ‘apple pie’ strategy – something that is difficult to criticize, and largely inoffensive. Such strategies are full of platitudes that amount to little more than a series of statements of the obvious, specifying the good things that the firm hopes to achieve. A quick way to discover whether an organization has a strategy is to ask them what opportunities have been rejected, which market segments they will not compete for, which capabilities will not be developed and which product or service benefits will not be offered.

Strategizing therefore often means deciding to stop doing something. This can be an activity that the organization does, a product or service feature, operation in a particular market, or a relationship with a specific partner. Stopping something and deciding not to do something are difficult, as they mean saying no to possible revenue – especially hard to do if what you stop doing is something you can do and have been doing for a while. In effect, taking a strategic decision can sometimes mean stopping doing something you are good at and know how to do, and starting doing something that the organization is new to, and is consequently not as good at.

Being good at something is not in itself sufficient reason to continue doing it. This is the competency trap that is responsible for many organizational failures – namely that organizations continue doing what they do because they are good at it, despite other firms being better and/or customers no longer valuing what they are good at (Levitt and March, 1988; Leonard-Barton, 1992). Viewed this way, the deciding factor whether to continue doing something is sometimes whether you can do it better or differently than others, in a way that cannot simply be copied; in other words, the organization needs to be sustainably better at it. Further, that what you are doing creates something that is valued by a growing and sufficient number of people. This is not to forget the highly uncertain nature of product value that shapes creative activity and cultural product. The demand and therefore value of a product or experience or service will always carry a high degree of uncertainty. The point about competing strategically is to consider how the organization is currently creating these products and services, to evaluate what it does and why, in order to ensure that it is not merely following a script but is making choices about how and what capabilities to employ. The content of cultural product is unavoidably and necessarily dynamic, a source of surprise and sometimes disappointment. How it is produced, distributed, explained and experienced are strategic issues that managers can analyse and experiment with, and decisions that they can take.

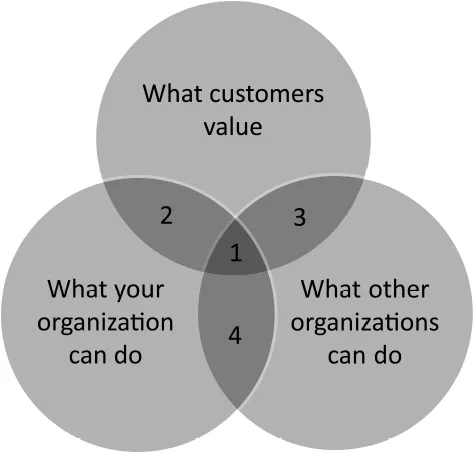

This perspective on the nature of strategic competition is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The strategy sweet spot

(Adapted from Collis and Rukstad, 2008: 89)

Position 4 is the worst situation to be in as it points to the possibility that part of what the organization is doing is no longer valued by customers. It may be because it is something that they have always done, perhaps they assumed had to be done, but actually it is not valued by the users or visitors. In this case the cost of doing it risks being a waste of money, and makes the product or service more expensive or less profitable, depending on how easy it is to increase the price.

Position 1 is the most competitive and therefore risks being the least profitable. Unless the organization in question is the largest and most well-resourced then competing in this space means direct and often costly competition. If the capabilities used by competing organizations result in products and services with similar benefits, distribution methods, use and consumption patterns, then unless demand is huge and the entry of new organizations is somehow restricted, price will very likely become the only source of differentiation. If price is the difference then organizations may fall into a price war involving the mutual destruction of each other’s profit margin. Unless the organization is confident that it can win such a war, force the competitors out of business and keep new ones out, then such a position is unwise.

Position 3 is perhaps the most hostile of all, as it requires learning how to do something that other firms can already do. This change, or diversification into another firm’s competitive space, can perhaps be justified if the view is that the incumbent firms are not particularly good at what they offer to customers and the organization believes it has transferable capabilities that will outperform them.

Better, the strategic perspective argues, is to occupy position 2. Here the organization’s capabilities are not matched by its rivals and are valued by customers. This is the sweet spot that offers the chance to create valued products and services produced and delivered for a sustainable profit. Conceptually straightforward but in reality this requires being able to see what others have not seen, of innovating and being different. There are ways to structure the exploration of such a position in the market but what is the most challenging aspect of competing in position 2 is the requirement to break the rules of the game, to depart from the script and risk being different. Organizations in the CCI are familiar with taking risks on the content of their products and services, but to be strategic they must carry this attitude over to the design and operation of the organization itself.

There are organizations in the CCI that are doing just that – searching for competitive space valued by customers and distinguished from competitors. In the chapters that follow we will use some of them to illustrate how they made the choices and developed the capabilities that allow them to create their strategies. Yet for some practitioners and the organizations they control, such a deliberate approach to the design and development of an organization is not believed to be appropriate for organizations in the creative economy. This is the view that whether particular activities are more or less profitable is not important when deciding what to do. The focus of the creative enterprise must be on the qualities of the product or service, be it the song, the film, the performance, the building or the dress. Profit is necessary, of course, but is a secondary concern, a by-product of artistic skill and creativity, not a consideration in how to organize that creative practice. Competing strategically in the CCI requires that if present, either explicitly or implicitly, this view be rejected, and that managing any tensions between creative and commercial rewards be seen as part of the task of the creative organization. In any case, such a view is an unnecessary simplification. Few would agree with the extreme idea that being creative is a licence for complete freedom over how the resources of the organization are used, nor with the idea that commercial practice involves the operation of measurement and control systems where the meaning and merit of the product itself is not relevant. Creative and commercial values are not, in the thoughtful creative enterprise, mutually hostile. As Matthew Taylor, chief executive of the Royal Society of the Arts, notes, ‘the best arts and heritage organisations are highly entrepreneurial’ (Taylor, 2013).

To summarize, being strategic involves looking at how choices are made and practices developed over the firm’s governance, resources and terms of competition. Strategy tackles how the firm is managed and organized, what capabilities and assets are developed and deployed, what products and services it delivers and what markets it competes in. This wide-ranging scope is made manageable by focusing analysis on whether and how these choices and arrangements contribute to the performance of the firm relative to that of its competitors. This is not, however, how the term strategy is frequently used. There is a good deal of confusion over what strategy is and what being strategic involves (Markides, 2004). It is necessary at this stage to deal with a few of these misunderstandings if we are to demonstrate the value of adopting a strategic approach to the management of organizations in the creative and cultural sector. In the spirit of strategy being shaped by decisions over what not to do (Porter, 1996), we will do this by identifying what strategy is not.

One of the biggest problems facing organizations wishing to become more strategic is the widespread belief that strategy is the same as planning (Mintzberg, 1994). For those holding this view, the yearly planning cycle with associated budgeting and target setting is the organization’s strategy. Clearly, in order to make things happen in an organized way, organizations need to develop a set of tasks and initiatives that can be set against targets and supported by financial and other resource decisions. The result, as many observers of business strategy note, is that this is not a strategy but a budget with explanations for what is going to happen. The problem with this is that the real heart of a strategy – the way in which an organization is going to create sustainable competitive advantage that reduces the competition’s ability to compete with it – is lost amongst the vast amount of procedural detail that organizations can assemble. One way of protecting the principle of a strategy being about the decisions taken over how to compete (which customers, against which competitors with what capabilities) (Mankins and Steele, 2006), is for organizations and commentators to argue for a paper limit, a restriction on the amount of space taken when writing the organization’s strategy (Shook, 2009). By restricting the strategy to between one and five pages, or in one example an A3-sized sheet of paper, the ability to obscure the strategic position that the organization wants to reach amongst the list of initiatives, actions and budgetary figures is reduced. In so doing, there is a greater chance that attention will be placed on the decisions and competitive positions that will guide the design of any plan, rather than the other way around.

As well as this practical objection to equating strategy with planning there is also a principled one. As plans are largely made up of what we know already – outcomes and variables that are measurable and manipulable because they have been previously identified and tested – planning is a very restrictive and short-sighted process. Creating new knowledge, insights and products and services is not an altogether rational process but often involves curiosity and play. Because developing a strategy and staying open to how it is performing requires generating new knowledge and coping with high levels of uncertainty, being strategic needs more than a planning approach (Martin, 2014). It requires ‘mindful practice’ – thinking with one’s hands, reflecting on what happens, adjusting and discovering (Jarzabkowski et al., 2007). As before committing resources, it is only sensible to attempt to predict the consequences if things do not work out. Within reason, the freedom to experiment, to create understanding, rather than attempting to understand before acting, is an important part of strategizing. Turning the familiar steps on their head, strategizing a case perhaps of ‘ready, fire, aim!’ (Masterson, 2007).

Spend any time talking to senior managers about their organization’s strategy and at some point they will begin searching their office for the most recent strategy document produced by the ‘Divisional Directors Group’ or some such executive-level body. This is the most important thing that a strategy is not. It is not a document. While we can agree with those management writers and organizations that limit the number of pages on which the strategy is worked out, it cannot stay there. Becoming a strategic organization requires more than a group of people who can analyse the competition, assess future sources of value and take decisions; it also needs an organization that can talk to itself. A strategy is a guide to action, a set of priorities and principles that inform behaviour and shape attitude. Unless it can be communicated effectively throughout the organization it will not be realized and will remain a document on a shelf. So, because strategy is both more and less than a budget with explanatory comments, and because strategy involves discovering what we do not know and developing new knowledge during action, it must not be treated as another word for a plan.1

The second thing strategy is not, is equally discomforting. Strategy is not equivalent to the pursuit of profit. Strategy involves the creation of a profitable competitive position made possible by particular capabilities developed by the organization. However, it is not about maximizing profit but selecting the degree of profit appropriate for the organization’s strategy. Too much profit and the organization may not be able to invest in the experimentation necessary to create new product or service benefits, explore new partnerships or discover new markets. The argument that strategy involves selecting a desirable level of profit rather than seeking its maximum point, is captured effectively in what is referred to as the ‘explore versus exploit’ decision (March, 1991). This is the recognition that sustainable organizations are built on two activities: first, exploiting the organization’s existing capabilities and assets to efficiently create products and services that are valued by customers; and second, exploring new ways of doing things and new things to do that may eventually become the future sources of profit. Organizations need to ensure they have the right balance between exploitation and exploration if they are to respond to social, technological and economic change. Successful organizations can be described as ambidextrous in that they need to be able to both work on improving established activities, and innovating and creating new ones (Raisch et al., 2009). Strategizing therefore involves managing these two imperatives and selecting when to focus on one or the other. This appears commonsensical, however, when we consider that this may mean stopping doing something that is currently profitable in order to devote time and resources to working out how to do something new. We can appreciate how strategizing involves overcoming some significant obstacles.

Finally, a strategy is not the same as having a set of objectives. Setting aspirations for the organization is necessary but insufficient to qualify as a strategy. Being the most favoured destination, supplier of choice, the number one or the best, may be motivating (in the short term) but does not help the organization explain to itself how it will compete. The same applies to more numerically described objectives based on return on investment, revenue or profit. These objectives do not explain the choices made in the pursuit of some form of unfair competitive advantage. They are what will happen if the strategy is successful; they are not the strategy. To conclude, strategy is not planning, the pursuit of profit or the setting of objectives; it is the choices made to create capabilities and assets that will enable the organization to reduce the ability of competitors to compete against them.

What are the creative and cultural industries?

One way of answering this question is to say what isn’t? Which industries do not involve some level of creativity? Which set of organized relationships between production practices, workers, products and services and consumers are not cultural? All organizational activity both takes place in, and contributes to, the production of attitudes, beliefs and values that pattern human behaviour and understanding – in other words culture, a system of understanding and learned behaviours that shape how we live and make sense of the experience. Organizations cannot somehow stand outside the culture in which their production practices are carried out. Their products and services are similarly used and experienced through the users’ and consumers’ cultural knowledge and behaviour. Equally, very few organizations do not require creativity to succeed, whether it be a creative approach to problem solving, the generation of product lines, ways to market, the identification of new customer groups or ways of managing or structuring the organization. The creative act, the application of new thoughts or the transfer of ideas from one domain to another in order to produce something valued by other people is a part of human and therefore organizational life.

Given the inseparable nature of culture and creativity from any organized activity, labelling a particular group of organizations as comprising the creative or cultural industries is therefore necessarily problematic. Defined at their most fundamental level, the suggested qualifying features of cultural and creative industries – the key role of interpretation in our valuation (and production) of products and services, and the importance of idea generation and execution to the practice of organizations – are not particularly distinctive. However, it is not the presence of culture and creativity that classifies organizations as belonging to a creative and cultural industry; it is the degree to which they shape production, distribution and consumption. The creative and cultural industries are recognizable by how much of the value of the product is symbolic. How much, though subjective, is important, as many products contain some symb...